The five greatest doping scandals in sport - and Kenya's marathon attempt to join in

From Ben Johnson and BALCO to cycling's EPO era and state-sponsored plots in East Germany and Russia, sport has been littered with drugs controversies. Kenya's is still unfolding

The London Marathon is on Sunday and it’s long been one of the great communal sporting occasions, and also one where I can’t trust what I’m seeing - in the elite races at least.

By “great communal occasions”, I don’t just mean from a UK point of view; there are six ‘big city’ marathons each year, in Tokyo, Boston, London, Berlin, Chicago and New York, and London will routinely draw the world’s best runners, biggest fields and raise gazillions of pounds for charities.

There were 20,000 applicants and more than 7,000 starters in the inaugural London Marathon in 1981. For this year’s race, the number of applicants was almost 600,000.

There have been between 40,000 and 50,000 starters in recent years (the pandemic years aside), with runners collectively raising the thick end of £1bn for good causes since the race began. So, absolutely, it’s a force for good.

But elite marathon running, especially in the past couple of decades, now falls for me into the category of “I can’t trust what I’m seeing”. I accept there will be lots of people, not least clean athletes, who will be offended by that viewpoint.

It’s absolutely possible to run a decent or even brilliant marathon time and not be taking performance-enhancing drugs to do so.

But in the same way it was hard to trust the integrity of the Tour de France and the other Grand Tour races in cycling’s EPO era, or the men’s 100m in pretty much any era, I struggle to accept elite marathons are fundamentally clean.

I’ll explain why in much greater detail in the second part of this series, with data about marathon-winning dopers, and details of the ongoing crisis in Kenya in terms of its drugs problem (and Kenyans have dominated the major marathons for a decade and more).

I’ll also provide new details about various problematic marathon runners who have red flags against their performances either because of close associations with figures banned for drug-related offences, and/or their own proximity to drugs and drug users. I’ll also publish, for the first time, the handwritten statement of a recent marathon world record holder who says he was tipped off each time he was drug tested in his native Kenya.

I’ve researched and written a lot about doping in sport over almost three decades. Back in 1998 I conducted a big survey into the prevalence of drugs in British sport. It’s funny now to remember that the British Cycling Federation declined to take part or let any British cyclists take part in that survey. I wonder why! Peter Keen, then the director of British Cycling’s World Class Performance Plan, said he thought that “academics, not journalists” should compile such a study.

I’m now of the view that Kenya’s doping problem is one of the great scandals of modern sport. Kenya’s Eliud Kipchoge, regarded as one of the greatest marathon runners of all time, agrees with me. He has won two Olympic golds and 11 of the big city marathons (four in London) and he has said the level of doping in Kenya is a “big embarrassment”.

In October 2019, Kipchoge undertook the INEOS 1:59 challenge, an attempt to run a marathon in under two hours, sponsored by petrochemical company INEOS, now owners of the cycling team formerly known as Team Sky. And he did it, clocking 1hr 59min 40.2seconds in Vienna, Austria.

He was assisted by 41 pacemakers who rotated in and out during the record attempt. The fact those pacemakers included multiple dopers (as I’ll detail tomorrow) makes his achievement somewhat problematic.

Is doping a problem in elite sport? Does it matter if some people are taking banned drugs to try to help them win? If you’re the co-owner of Wrexham and you’re making a documentary to popularise cheating in sport, perhaps not. I’d argue that most sports fans would rather that people didn’t cheat with drugs.

But cheats have existed as long as organised sport has existed and below I detail five of the biggest drugs scandals in sport. The list isn’t exhaustive by any means but it provides a snapshot of some of the most notorious and expansive episodes of cheating.

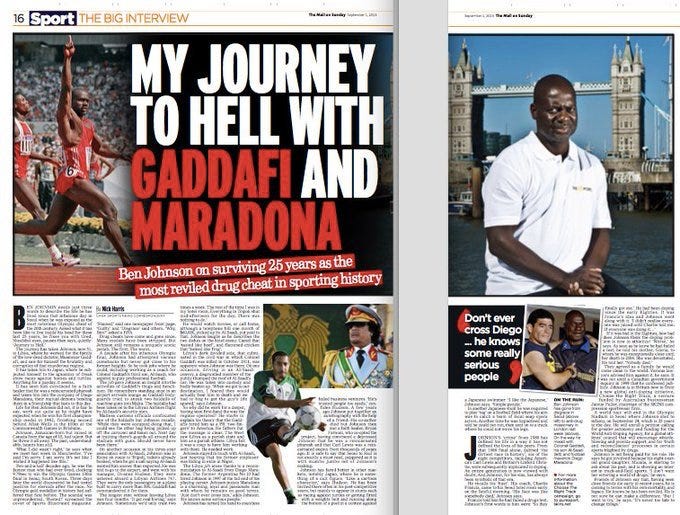

Ben Johnson - the most notorious Olympic doper ever?

Ben Johnson was 26 when he became arguably the most notorious single cheat in the history of sport up until that time. The Jamaican-born Canadian sprinter won the 100m gold medal at the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea, in an astonishing record-setting time of 9.79 seconds. The next day his routine post-race urine sample came back positive for the banned performance-enhancing steroid stanozolol.

Overnight Johnson became a pariah, lambasted as the baddest man in athletics, a dirty cheat, the first Olympic gold medallist in arguably the Games’ most famous single event to test positive after winning. His world flew off its axis and his life was transformed for ever, for the worse.

Arguably he has never recovered from the infamy of what happened 36 years ago, and I for one have considerable sympathy with him for the way he was uniquely tarnished. “Busted!” screamed the cover of Sports Illustrated magazine. “Shamed” said one newspaper front page. “Guilty” and “Disgrace” said others. “Why, Ben?” asked a fifth.

So why do I have sympathy for him? First, most of his competitors in that 1988 Olympic final were also dopers, as were many other track and field athletes of the era. We later found out that Carl Lewis, who was subsequently awarded the 1988 gold, had tested positive for stimulants that would have seen him booted off the USA team. Linford Christie served a drugs ban, as did fellow 1988 finalist Dennis Mitchell.

Second, Johnson’s response to his positive test was that he wanted to be open about what he’d been doing. His coach, Charlie Francis, had come to his Seoul hotel room early on the fateful morning he got the news. “His face was like somebody died,” Johnson said. Francis told him he had failed a drugs test.

Johnson's first words to him were: “So they finally got me.” He had been doping since the early Eighties. It was Francis's idea and Johnson went along with it. “I didn't realise everyone was juiced until Charlie told me. If everyone was doing it, I needed to as well.”

Johnson was persuaded not to come clean, including by officials from Canada’s Olympic association; he was, in effect, told to keep his mouth shut.

My third reason for having sympathy with Johnson is I spent one of the most extraordinary evenings of my career with him, in a hotel bar in Manchester in 2013, talking for hours and hours about his life and career.

His life after Seoul became a freak show. He worked for the family of the late Libyan dictator, Muammar Gaddafi, which on one occasion saw him carry a holdall of machine guns through customs.

He appeared on Japanese game shows, racing against horses and, underwater, against turtles. He became Diego Maradona’s personal trainer, their mutual demons helping them forge a close bond that lasted until Maradona’s death.

For many long years he felt deeply embittered that he was the villain of his day when so many other dopers were hailed heroes. On that night in Manchester 11 years ago, late into the night, I asked Johnson what it had been like to live inside his head for the previous 25 years.

He fixed me with tired, bloodshot eyes, paused, and then said, quietly: “A journey to Hell.” You can read my interview with Johnson here.

BALCO: a scandal that rocked America

The Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (BALCO) was founded in the early 1980s by Victor Conte and supplied banned, performance-enhancing drugs to high-profile sportspeople from the USA and Europe until the early Noughties.

BALCO became the target of an investigation in 2002 when federal agents began looking into allegations that it was the hub of a drugs operation. Then the United States Anti-Doping Agency, USADA, started looking at the lab, having received a tip-off that Conte was supplying an undetectable, designer steroid. That tip came with a syringe filled with a steroid and it turned out the tipster was Trevor Graham, the former coach of sprinters Marion Jones and Tim Montgomery. They had both won gold medals at the 2000 Sydney Olympics among many other prizes.

Conte worked with a chemist from Illinois, Partick Arnold, who designed a concoction of undetectable drugs which were then distributed by a personal trainer, Greg Anderson.

Arnold devised a regime of doping that if carefully administered would largely go undetected. His potions, mixed with various legal minerals, contained combinations of five major banned drugs: erythropoietin (EPO), human growth hormone, the stimulant modafinil, testosterone cream, and tetrahydrogestrinone (aka THG, also known as The Clear).

Conte and his associates sold these drugs from 1988 to 2002 to a huge array of sportspeople from sprinters Kelli White, Dwain Chambers and Konstantinos Kenteris, to shot putter Kevin Toth, and middle distance runner Regina Jacobs.

Baseball star Jason Giambi admitted to a grand jury in 2003 that he had used steroids and HGH. His brother Jeremy was also supplied with drugs by BALCO. Barry Bonds, who set records for the most home runs in a season and a career, was the most famous baseball player implicated, but has never admitted taking drugs. The most notable NFL player implicated was Bill Romanowski, a four-time Super Bowl winner. He admitted to using steroids and HGH supplied by Conte.

Russia’s state-sponsored doping in the Putin era

Regular readers of Sporting Intelligence or followers of @sportingintel will know the story behind the story of Russia’s state-sponsored doping programme, a scandal I’ve covered extensively from the start.

In summer 2013, my colleague Martha Kelner and I published an investigation about doping in Russia, revealing that Moscow lab boss Grigory Rodchenkov was at the heart of a massive state-sponsored doping and cover-ups programme. We told the IOC about it, and our story said Russia’s aim was to corrupt the forthcoming 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics.

We even quoted a senior Russian sports official saying Russia would dope their athletes, win loads of golds and get away with it.

The IOC completely ignored this most blatant of warnings, did absolutely nothing to investigate Rodchenkov, and let Russia get away with it.

You can read the story behind that story here. Of course the Russian scandal went on and on and on, and the fallout resonates today. More than 1,000 sportspeople from more than 30 sports were known to be involved; among many stories I broke on the scandal, I revealed that the entire 2014 Russian World Cup squad were beneficiaries of the plot, some of whom were dopers and others given state protection in case they were caught.

You may have seen the Oscar-winning documentary, Icarus, about Rodchenkov fleeing Russia for America to expose the scandal. If not, you can see it on Netflix. Readers of Sporting Intelligence recently voted it among the best sports documentaries ever.

Cycling’s EPO era & the world-beating cheating of Lance Armstrong

The Festina Affair of 1998 involved loads of cyclists getting busted for drugs, and numerous riders admitted to taking EPO. It had been going on for years and carried on for a lot more. Hilariously the 1999 Tour de France was variously nicknamed the “Tour of Renewal” and “The Tour of Hope” to suggest that cycling was entering a golden new age of drug-free riding.

Of course 1999 was the year that Lance Armstrong won his first of seven consecutive TDFs, and we all know now he achieved that.

Cycling, particularly in the Grand Tours, has had a drugs problem almost as long as the sport has existed. The British cyclist Tom Simpson, died age 29 in 1967 during an ascent of Mont Ventoux with amphetamines and alcohol in him, a fatal diuretic combination.

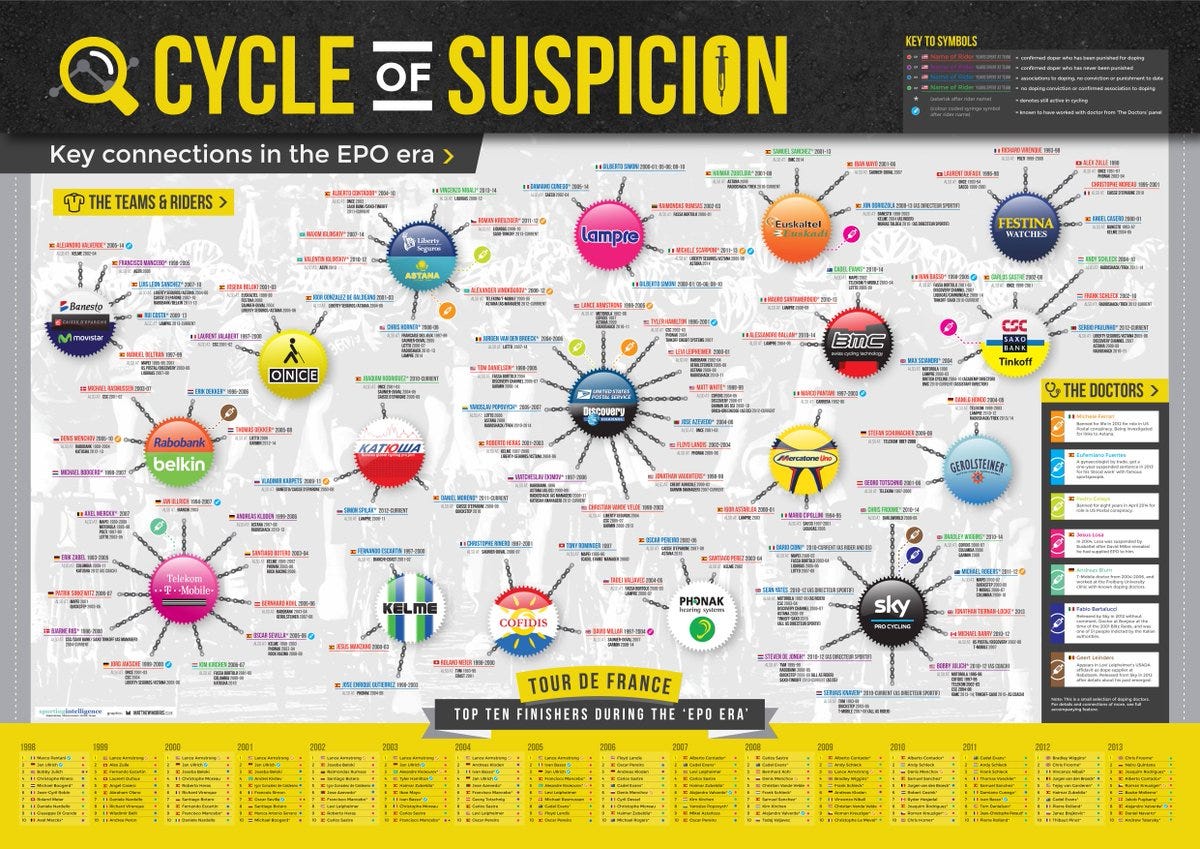

In 2014, as we waited for the publication of the findings of the Cycling Independent Reform Commission, myself and Teddy Cutler conducted an audit of the key teams and players of the EPO era in cycling. You can read about that here. We also produced a poster (below) mapping the known dopers and their links to doping doctors and other enablers. We underestimated quite how tainted modern-era cycling was by drugs.

In a way I find the doping in cycling to be more shocking that Russian state-sponsored doping. Cycling’s global governing body, the UCI, knew full well for a long time that most of the riders in the Tour de France and other key events were juiced to the eyeballs, to the extent that they even introduced haematocrit testing to try to keep the cheating at a certain level.

They never seriously showed any sign of wanting to clamp down on drugs. In that regard, they are, I suppose, like most governing bodies in most sports.

East Germany’s formal (but secret) doping programme

East Germany’s former Minister of Sport, Manfred Ewald, imposed blanket doping on the athletes in his country from 1974, having already been doping lots of them previously. This led to athlete harm beyond imagination, often as a result of drugs administered without their knowledge. It’s a fascinating and massively depressing tale. And it led to loads and loads of Olympic medals.

East Germany was fifth in the medals table in the summer Olympics in 1968, with 25 medals, nine of them gold. By 1972 they were third, with 66 medals, 20 of them gold. By 1976 they were second with 90 medals, 40 of them gold. By 1980 they still second, but with 126 medals, 47 gold. They boycotted the 1984 Games but were back in second in 1988, with 102 medals, 37 of them gold.

Brilliant article again, Nick.

Great writing.