User Beware: the bottle behind the NDAs signed by 91 UK athletes before London 2012

This is the story of the investigation that connected an experimental performance-enhancer, Government funds, gold medals and the man charged with recalibrating Manchester United

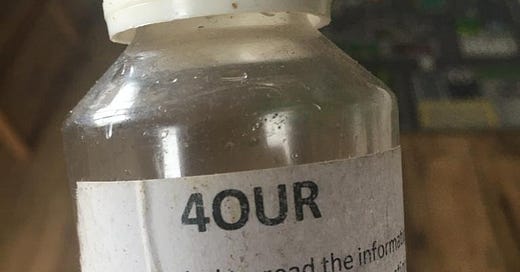

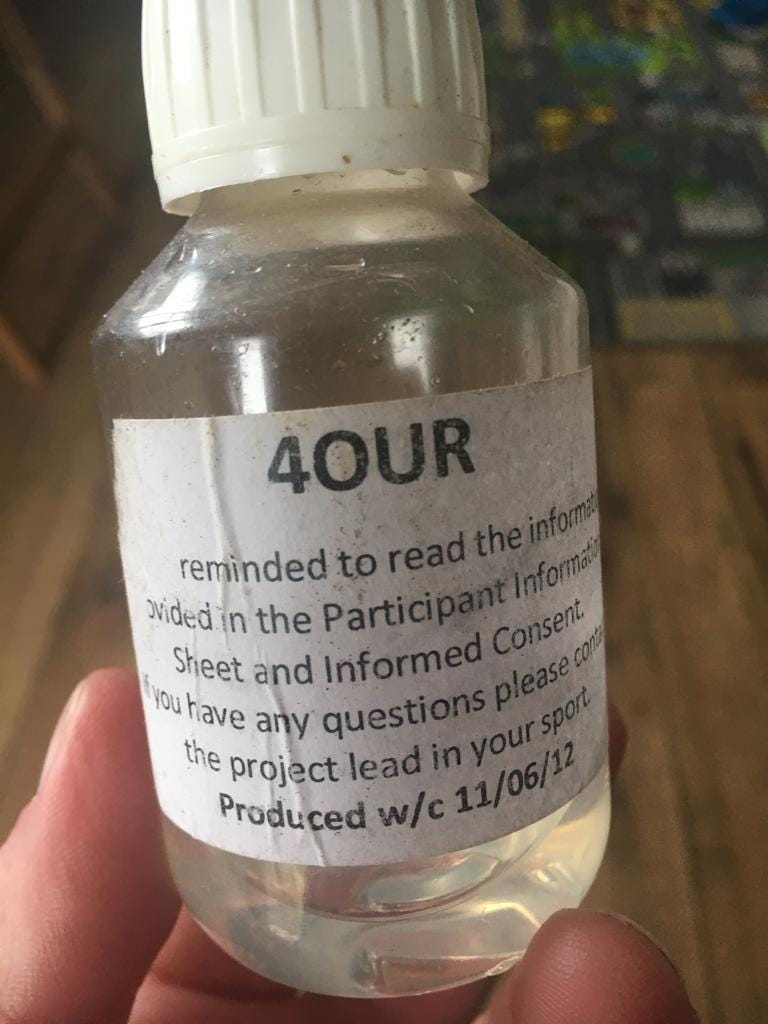

This is a bottle of an experimental, performance-enhancing substance, secretly acquired using hundreds of thousands of pounds of public money by UK Sport, in an attempt to help British Olympians win medals at the London 2012 Games.

At that time it was a ‘novel nutritional intervention’ called Delta G, developed for US Special forces, to boost endurance. While it was not licensed for human consumption at the time, similar products are now commonly used in elite sport – they are known as ketones, usually consumed as a drink, and replicate the chemicals produced by the liver when it breaks down fats for energy.

However, back in 2012, Delta G was not commercially available, nor was it medically approved.

Among those who tried using it that summer were some of the athletes in the British cycling team, and also some of the cyclists at Team Sky – now known as Ineos Grenadiers.

This particular bottle, as the date on the label shows, was produced in the week commencing June 11, 2012, and was shown to me by somebody with first-hand knowledge of British cyclists’ experiments with it. This is the first time this photo has been published.

The 2012 Tour de France ran from June 30 to July 22 that year, and was won by Bradley Wiggins, who later became Sir Bradley. A source close to Wiggins confirmed he was among British Olympians who tried Delta G, but insisted he didn’t find it especially beneficial and stopped taking it.

“Some of the cyclists were totally invested in trying it,” said another source. “They’d do anything that might give them a performance edge, not least as this was endorsed by UK Sport, albeit secretly.”

The London Olympics then ran from July 27 to August 12, 2012. British cyclists collectively won eight gold medals, two silvers and two bronzes at those Games. The host nation dominated the cycling medal table.

The golds included Wiggins winning the time trial, Chris Hoy and Victoria Pendleton winning their keirin events, and assorted pursuit and sprint titles.

It has never been confirmed which riders took Delta G and which didn’t, but 91 British athletes were in a secret trial, across eight sports including rowing, swimming, athletics and hockey.

The most senior person at both British Cycling and at Team Sky in 2012 was Dave Brailsford, later Sir Dave, who will soon be taking a hands-on role at Manchester United as a trusted advisor to incoming minority shareholder Sir Jim Ratcliffe.

To be clear, this is not an article about doping; rather it seeks to demonstrate that at the top end of elite sport, most competitors and their coaches will exploit any performance advantage open to them. In the case of Delta G in 2012, those 91 ‘guinea pig’ athletes not only signed waivers saying it would be their own fault if Delta G made them ill, but also non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) promising they wouldn’t reveal what they’d been taking.

Such was the concern that British Olympians would be perceived to have an unfair advantage if it leaked that some were taking ketones at London 2012, UK Sport had a communication strategy in place to propagate the narrative that Britain was simply “ahead of the curve” compared to its competitors – akin to the ‘marginal gains’ philosophy that would soon become a cornerstone of the Brailsford story.

Brailsford has previously denied that Team Sky have ever used ketones. Similarly, Chris Froome, in 2015, said he had never heard of ketones and that Team Sky “100%” did not use them. It is feasible, of course, that individual athletes were using ketones in 2012 without telling their coaches.

Delta G was originally developed by scientists at Oxford University with $10million of funding from the American Department of Defence. The reason? To allow US Special Forces to operate for longer behind enemy lines, with fewer rations.

We have obtained a copy of a PowerPoint presentation from the creator of Delta G, Professor Keiran Clarke. In this presentation, by way of a marketing blurb, Clarke claims that Wiggins was an “early adopter” of ketones and used them to break “world records at the Olympics and Tour de France”.

Ketones have never been prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) but the fact that Team Sky either did not know or did not disclose that some riders were using them underlines the controversy around them.

As recently as 2020, Herman Ram, the head of the Dutch anti-doping agency, said his organisation advised against the use of ketones by athletes.

“It is a legal nutrition but, at the same time, too little is known about the possible health consequences,” he said. “That makes it a grey area. It is not on the doping list, but if we receive questions from athletes, we advise them not to use ketones.”

UK Sport had to seek special approval from WADA and UKAD before providing the substance to the country’s Olympians before London 2012.

Despite being granted this approval, UK Sport could not guarantee to these same British athletes that ketones were fully compliant with WADA rules.

UK Sport produced a ‘participant information sheet’, effectively a waiver, exempting UK Sport from responsibility if the athletes’ use of ketones led to problems with anti-doping authorities.

“UK Sport does not guarantee, promise, assure or represent that use of ketone esters is absolutely World Anti-Doping Code compliant and therefore excludes all responsibility for use of the ketone ester,” it said.

In other words, if an athlete failed a drugs test after taking the substances given to them by UK Sport — either because they were contaminated with banned substances, or WADA made the substance illegal — it would be the athlete’s fault, not that of UK Sport.

Ketones were not approved for commercial use at the time, and could only be supplied to humans in the context of research. As such, UK Sport commissioned a ‘study’ in which 91 British Olympians would be provided ketones to assess their performance-enhancing effect.

In the participation information sheet prepared by UK Sport, athletes were told: “The ketone ester used in this study is not commercially available and can only be administered as part of a research trial.”

In reality, the selected athletes had free reign to take the performance-enhancing drink at the London Games – while it was not available to any of their rivals.

UK Sport was able to gain access to the substance by contacting the US military, who in turn pointed them to Oxford University, whom UK Sport paid to conduct trials of the substance in rowers and cyclists.

Invoices show UK Sport paid Oxford’s research team £4,000 in early 2011 for a trial involving rugby players at Bath University; and then £183,600 later in 2011 for the trials on rowers and cyclists; and then £42,115 in early 2013 as a further “research grant” for Delta G studies on athletes.

These invoices and confidential documents were obtained by us after submitting a series of Freedom Of Information requests (FOIs) to UK Sport throughout 2020, and we first revealed details of what had happened in 2012 in an investigation published in the Mail on Sunday in July 2020.

The fact that British sport was veering into grey areas is evidenced by the language in the documents. A document for UK Sport board members in October 2011 said: “A communication plan will be needed with the media to mitigate any negative perceptions and publicity. The publicity focus will need to be on the quality of the science ... and the fact that the UK is ahead of the curve compared to its competitors.”

It added: “If others are aware UK Sport is linked to the project ... the risks will be around perceived unfair competitive edge. Current proposals are looking to ensure any scientific publications are released post London 2012.”

All athletes had to sign NDAs to get access to Delta G. UK Sport told them: “This means you cannot talk to anybody outside of the research team and your peer group, i.e. athletes and coaches who have also signed this NDA, about the details of this study, especially not about the type of nutritional intervention you are testing.”

Ultimately, the existence of this secret research project was not exposed at London 2012, or indeed until 2020, when we covered it in the MoS.

The ketones produced by Oxford were unpalatably bitter, hence the need to be mixed into (slightly more) palatable drinks. Lab-based trials in rowers and cyclists appeared to show a 1%-to-2% performance benefit.

A confidential ‘road map’ memo stated: “The [UK Sport] aim is to implement the use of Delta G with targeted athletes and sports in the period leading into and during London 2012 with events greater than five minutes’ duration and multi-event athletes. These sports include cycling; hockey; sailing; athletics; swimming; modern pentathlon and select others.”

More than 40% of athletes using Delta G ended up with side-effects including vomiting and gastrointestinal upsets, and 28 individuals stopped taking the substance for this reason. A further 24 later withdrew from the scheme because they thought the substance was in no way beneficial to them.

We discovered all of this partly by accident, having started following a money trail of historic expenditure by UK Sport and asking: “Where did this money go?” Hence the FOIs. As we dug some more, we stumbled across an obscure academic paper revealing what happened when 91 athletes were used as guinea pigs in an Olympic year.

As we head for Paris 2024, how do we know that similar secret testing of products has happened since, or is even underway as the Games approach? Answer: we don’t!

Ed Willison has been a long-time contributor and partner in investigative projects, mostly on doping stories, for both Sporting Intelligence and The Mail on Sunday. His own Substack, Honest Sport, can be found here.