'Tis the season to sack managers, tra-la-la-la-la, la-la, la-la. But is it worth the pay-off?

The average "lifespan" of a manager / head coach across Europe's top divisions is 1.3 years. In England it's not quite as bad but clubs waste many millions on firing bosses.

Before giving you some extraordinary statistics about managerial sackings in English and Scottish football - and insight into how much money that costs - I want to thank every reader who has come to Sporting Intelligence this year, not least those who’ve subscribed and supported my work financially. Without that, it would not be viable.

Next month we’ll reach the first anniversary of reviving Sporting Intelligence, dormant for several years for reasons most of you know. It’s been quite a ride already and I know 2025 will bring some of the most significant stories of recent decades, not least Man City’s “115 case” verdict.

As for 2024, at the bottom of this piece I’ll give you my three sporting highlights of the year. I wish you a good holiday season, and a peaceful and healthy 2025. I’ll be back in early January.

The sacking season in English football is in full swing with 11 of 92 the clubs in the top four divisions (or 12%) appointing a new manager in the past month alone. Eight of those appointments came after the board or owners sacked the previous manager. At the three other clubs, Reading appointed a new manager after Rubén Sellés left for Hull, while Jon Brady (Northampton) and Neil Harris (Millwall) resigned for personal reasons, creating vacancies.

No fewer than 22 clubs of the 92 in the Premier League and Football League have changed their managers since the start of this season, usually after a sacking. That’s almost 24% of clubs getting rid of a manager inside four months. (Fleetwood sacked Charlie Adam last night; it’s hard to keep up).

In Scotland’s SPFL, the comparable figure is 19% this season, or eight clubs from 42 switching managers this season, most of them sacked, at Raith, Arbroath, Stranraer (a resignation not a sacking), St Johnstone, Hearts, Inverness, Clyde and Forfar.

No fewer than 51 of the 92 clubs in England’s top four divisions (55%) have changed manager at least once in the past year.

The eight English clubs replacing sacked managers in the past month are Saints (Russell Martin sacked a week ago yesterday), Oxford (Des Buckingham sacked), Wolves (Gary O’Neil sacked), Burton (Mark Robinson sacked), Bristol Rovers (Matt Taylor sacked), Hull (Tim Walter sacked), Leicester (Steve Cooper sacked) and Coventry (Mark Robins sacked).

What is utterly extraordinary is how many years most of these managers had remaining on their contracts and therefore how expensive it has been to get rid of them, because typically a club will need to pay them for most if not all of their contracted years.

Russell Martin signed a new contract in July this year that was supposed to keep him at Southampton for three more years until 2027, but he was binned after five months in a termination costing millions.

Des Buckingham signed a three-and-a-half year deal at Oxford in November 2023 and was sacked after 13 months,

Gary O’Neil at Wolves signed a deal to keep him at Molineux until 2028 … in August this year, and was binned after months.

Mark Robinson was head-hunted from Chelsea in June this year to become Burton’s new manager on a multi-year deal. The club then broke records for the amount of players they bought in one window before sacking Robinson months later.

At Bristol Rovers, Matt Taylor was appointed on 1 December 2023 on a three-and-a-half year deal and lasted less than a third of that.

Over at Hull, Tim Walter signed a three-year deal to take charge of Hull in the summer of this year and lasted 18 games before being canned in November.

Steve Cooper at Leicester signed a three-year contract this summer and was binned after 15 games.

Mark Robins at Coventry agreed a new four-year deal to 2027 in May 2023 and was sacked after a season and a bit.

Taking these eight managers as an example, they had signed new or renewed contracts for a combined total of 26 years, and were sacked after collectively being employed for five years, or less than 20% into their deals, on average.

If these managers had good advisors and lawyers when signing, then those clubs will be wasting more than 80% of monies committed to their contracts.

The situation in England, by the way, is actually more stable than in many European countries, where a recent “benchmarking” report from UEFA (PDF below, start at page 47), details how the average “lifespan” of a coach in the top divisions of Europe is 1.3 years.

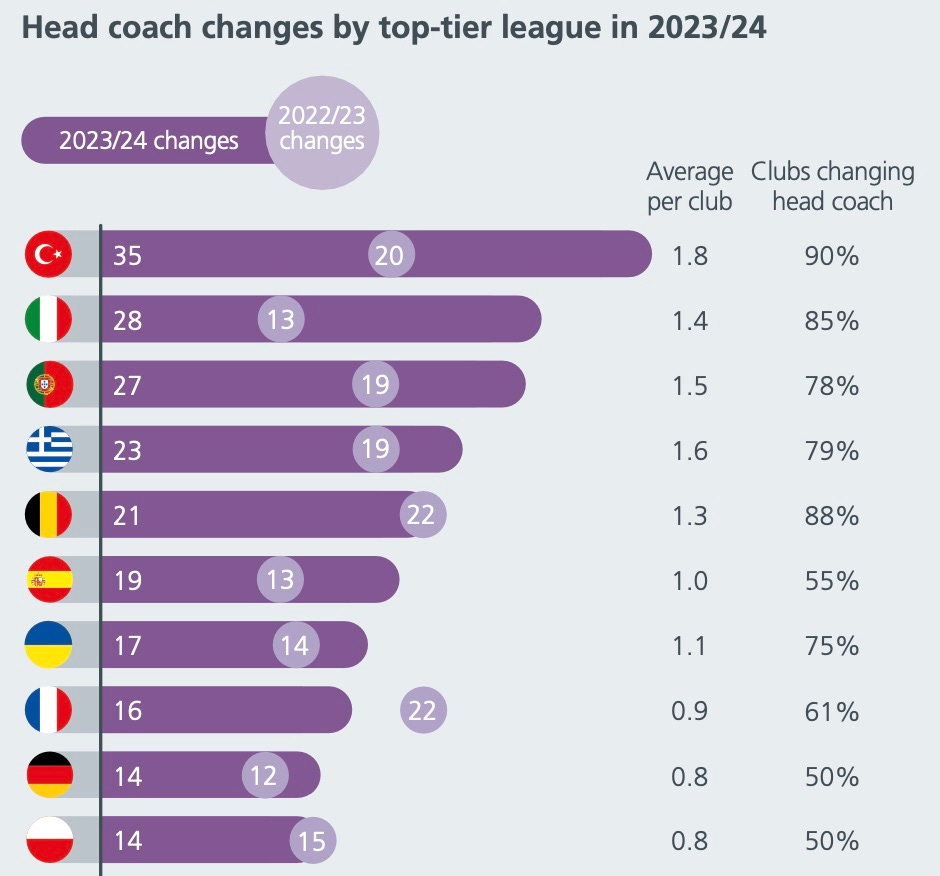

As the graphic below shows (source: UEFA), the 20 clubs in Turkey’s top-division Süper Lig made an astonishing 35 managerial changes in the 2023-24 season, or an average of almost 1.8 per club, with 90%, or 18 of the 20 clubs, making at least one change.

The graphic shows the comparable details for the top divisions in Italy, Portuga, Greece, Belgium, Spain, Ukraine, France, Germany and Poland.

So how much do managers earn?

Coming back to England, and a couple of studies I’ve overseen about managerial pay, football managers’ earnings vary hugely depending the “size” of a club, its income, its ambitions and the division in which it is operating.

It is typical that managers’ remuneration will have significant incentive-based pay depending on whether they are trying to qualifying for Europe, or divisional play-offs, or simply trying to avoid relegation.

I conducted a research project in the 2004-05 season into managers’ pay in association with the League Managers’ Association, effectively a managers’ union which describes itself as “the collective, representative voice of all managers” across England.

A second piece of research was undertaken this season for a consultancy project, attempting to ascertain the salaries of a cohort of current managers and analysing whether there are patterns of pay across that genre, and if so, how it might relate to a club’s income or wage bill.

The managers’ survey in 2005 involved more than 60% of the 92 managers across England’s Premier League and three divisions below that, and established that basic annual managerial salaries in England ranged from £20,000 to £4.18m per year. The data on wages was provided on a confidential basis by a representative sample of clubs across the four professional divisions.

In the Premier League, the basic wage range back then was £600,000 to £4.18m per year but informed sources say the typical "mid-range" (median) salary in the top division was around £1m per year plus bonuses, which varied from club to club.

In the Championship, basic salaries ranged from £95,000 to £450,000 per year, with a ‘typical’ mid-range salary of £200,000 plus bonuses. In League One, the spread was £55,000 to £200,000, with the mid-range salary at £80,000 plus bonuses. In League Two the spread, strictly speaking, ranged from nothing to £100,000 per year.

Ramon Diaz, then manager at fourth-tier Oxford, had no work permit and officially worked for free, while another manager was known to be on a bonus-only package. The mid-range salary in League Two was £55,000 a year plus bonuses, with the lowest paid manager understood to be earning a basic £20,000.

The highest paid manager in Britain that season, 2004-05, was Chelsea’s Jose Mourinho, earning a basic £4.18m a year, with potential bonuses of seven figures. Chelsea’s total club wage bill was £108.9m that season. Given that Mourinho managed his club to the Premier League title, a League Cup win and the semi-finals of the Champions League, I would expect his total earnings that season would be at least £5.5m, or roughly 5% of his club’s total wage bill, and probably more.

I recently wondered if there was a relationship between “typical” managers’ salaries in each division in 2004-05, as established by the survey and research, and player’s salaries. In 2004-05, using average wage data as calculated by Sporting Intelligence and accepted across multiple High Court and arbitration cases, the average player salaries in 2004-05 were as follows, with the “mid-range” managers’ salaries for that season alongside them:

With the caveat that this looks at a single season, there is nonetheless a striking similarity between average pay by division and a manager’s mid-range salary in that division. With a further caveat that there will be large variations between clubs and between payment structures, including bonuses, it seemed that, roughly, a manager might expect to earn around 4% of a club’s wage bill in any given season, or approximately that of a player’s average all-inclusive wage at that club.

Moving to the contemporary Premier League I used various sources to compile a list of current salaries for 16 Premier League managers. Their average basic salary was £5.8m, which is bigger than the approximate £4m-a-year current average top-flight PL player salary (inclusive of bonuses and benefits), but the £5.8m was skewed upwards by two outlier big salaries.

The range of basic salaries in this group of 16 was from £1.5m basic to £20m basic, and ranged from 1.1% of a club’s wage bill to 5.5% of a club’s wage bill, averaging 2.7% of a club’s wage bill. The median salary among the 16 was £4.5m, and the median percentage of a club’s wage bill was 2.5%.

There is no conclusive documentary evidence to support this but it is my hunch based on various conversations with club executives is that managers in this group on the lower salaries (at smaller clubs) can earn significantly more via bonuses, not least from Premier League survival. On this basis I might guesstimate the average bonus-inclusive salary of a manager might now be 3-4% of a club’s wage bill.

Football clubs are undoubtedly hugely wasteful (as a collective) in dishing out contracts to mangers they then sack quickly and have to pay off.

It is any club’s prerogative of course to hire and fire arguably the single most important employee, often. Perhaps next year I’ll write a follow-up piece that tries to quantify whether this expenditure is worth it, or indeed quite how much a typical manager actually adds value to a club.

Evidently some managers (a minority) are utterly transformational, for example Pep Guardiola at Manchester City, although not in recent months. I’m inclined to think that most managers don’t make that much difference to a team’s performance.

My personal sporting highs of 2024

1: Southampton won the Championship play-off final at Wembley and I was there. I wrote about it in this piece: “What’s the point of football? (Apart from everything)”.

2: My mum got to meet her sporting hero, Lewis Hamilton. I wrote about it in this piece: “The Pope, Lewis Hamilton and my mum: a week that reminded me of the joy of sport.”

3: The 2024 Olympic Games in France were a triumph. I wrote about that in this piece: “Paris 2024: Shades of grey in the City of Light as France delivers glory Games.”

This piece is one of numerous articles on this site that is free to read for everyone. But the work of the Sportingintelligence Substack, not least investigative pieces on the smoke & mirrors of Man City’s legal battles, the true scale of match-fixing in England, the ‘Skyfall’ series on drugs in British cycling, part 1 of 5 here, match-fixing in tennis, and much else, is unsustainable without paid subscriber support. Try it and read everything. There’s a vault of more than 1,700 pieces on this site, going back to 2010. And if you’re not getting value for money, unsubscribe. Thanks!

Interesting article. I often wonder about the ACTUAL impact of a head coach. Of course, they play an important leadership role but club Chairmen seem to think that every weakness is due to the coach. Clubs like Man U and Rangers have structural weaknesses, yet they fire coach after coach.

I'd be interested to to see some analysis on that front.

You will be able to place the year better than I, it was the year Chelsea sacked Avram Grant. In the same month we needed Chelsea's then owner to write a cheque for $174mm to buy a natural gas business in southern Russia.

We were ushered in to make the pitch and the ask - to which the response was (translated) what's $170mm, I'm paying four (excellent Russian swearword from prison language) managers it's like a drop in the ocean.

So off we went and bought our gas field - and the Putin invaded Crimea and everything changed.