The Truth About Wages (part one)💵

The £4.3m tackle - cracking the code of injury compensation in the Premier League

The best kind of journalism – built on extensive research and infallible evidence – stands the test of time. It’s what first attracted me to Substack and it is why – for my first post – I’m revisiting a story that I started reporting on over two decades ago. The idea started in my head and ended up in the High Court. It changed lives along the way. Not every article can create such an impact, but it’s what I aspire to on this platform

THIS is a story about football, money, the law, why facts are sacrosanct – and why journalism needs to be more rigorous than ever to earn trust in an era of so much fake news.

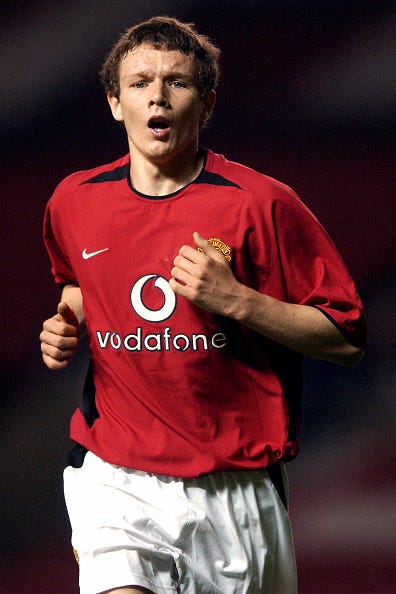

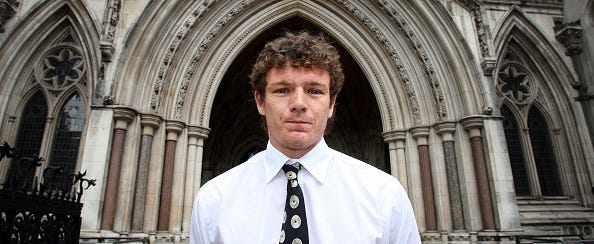

It’s also a story about an 18-year-old footballer, Ben Collett, who had never played a first-team minute when his leg was broken in two places in a reserve game in May 2003.

He was a highly rated prospect at Manchester United at the time, earning £460 per week, or £23,920 per year. Five years later he was awarded a minimum of £4.3m in damages at the High Court for a career that never was.

The injury effectively ended any dreams Collett had of making it as a Premier League star. And he definitely had the potential.

Just one week before his leg was broken in a match against Middlesbrough, Collett was part of the Manchester United youth team which won the 2003 FA Youth Cup final. That same month, Collett received the Jimmy Murphy Young Player of the Year award for being United’s most promising youngster of the season. You’ve probably heard of some of the other winners down the years, including Ryan Giggs (1991 and 1992), Paul Scholes (1993), Wes Brown (1998, 1999), Danny Welbeck (2008), Marcus Rashford (2016) and Alejandro Garnacho (2022).

Collett’s £4m-plus payout ultimately arose because of a simple idea for a feature in the sports pages of The Independent newspaper in 1999. The idea (mine, by the way) was: ‘What do footballers really earn?’

That was one of many questions I proposed we should ask professional players at the 92 clubs across the Premier League and Football League. Teaming up with the Professional Footballers Association (PFA), The Independent sent questions on a dozen subjects to the home addresses of over 2,500 footballers. Those questions included:

Should there be a quota on foreign players?

Which referees do you consider the best?

How much voluntary work do you do as part of a club community scheme?

And the final question in the survey:

What is your basic weekly salary?

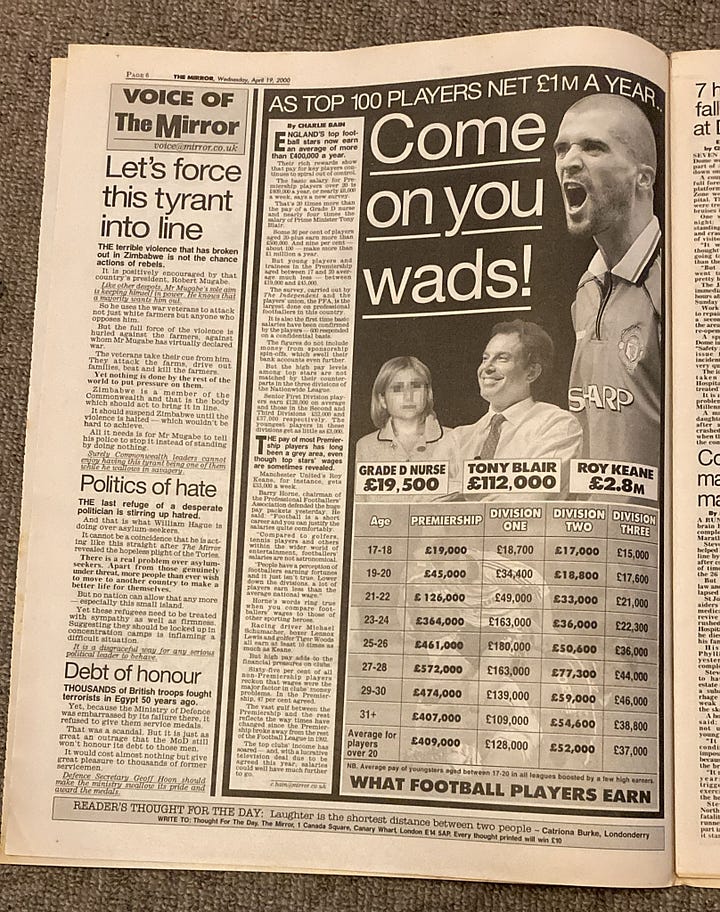

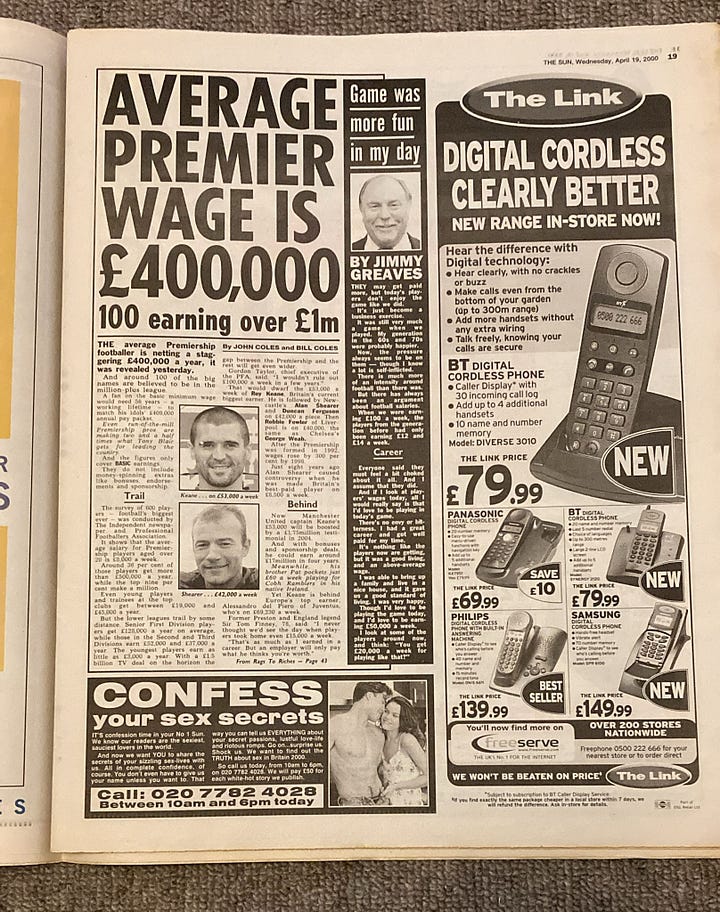

The process was lengthy and the data analysis had to be meticulous, and cross-checked with the PFA. But the response rate had been high: more than 600 players had responded, across all four divisions and a wide age spectrum. And so, in April 2000 The ‘Indie’ ran a full week of features about the realities of life as a pro in England, including a detailed look at how much players earned.

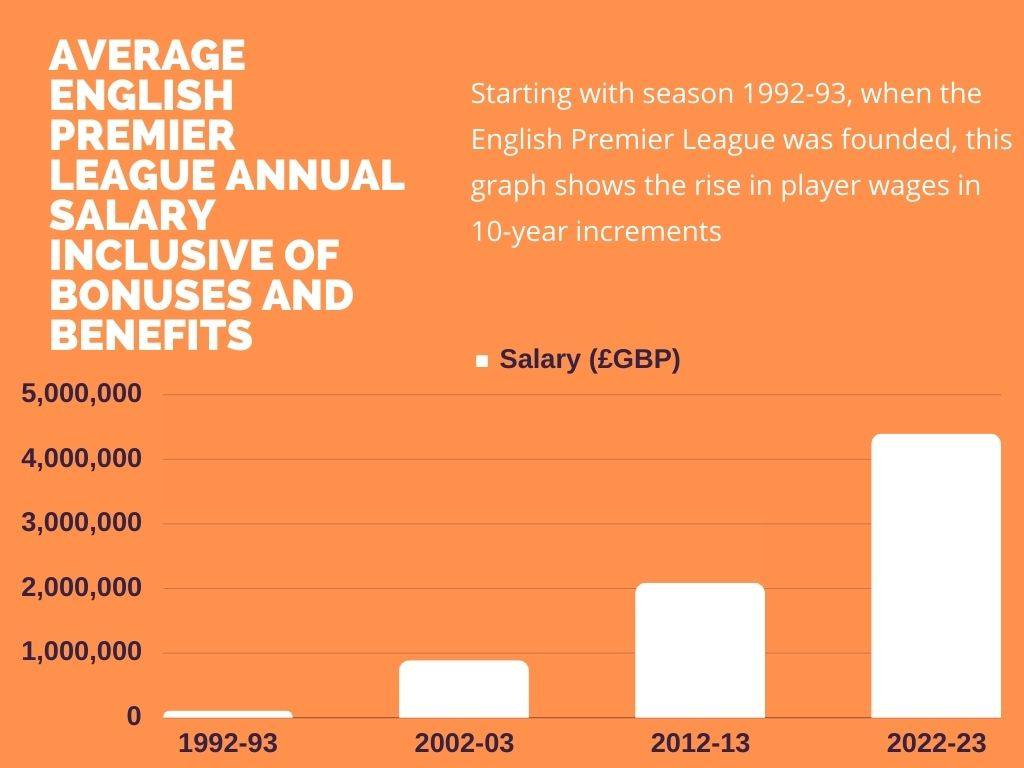

One headline finding was that the average basic wage in the Premier League during season 1999-2000 was £409,000 per year, while in the Championship it was £128,000. In League One it was £54,600 and in League Two it was £38,800. All these figures were before signing-on fees, bonuses and benefits.

When we repeated the survey in season 2005-06, these figures had risen to £676,000 in the Premier League, £195,750 in the Championship, £67,850 in League One and £49,600 in League Two.

By 2006, our data was more granular still. We established that, by then, around 29.5% of Premier League players had basic pay of more than £1m per year; that the highest-earning age group was 28-year-olds (on an average basic of £1.16m per year); and that, by position, goalkeepers earned the least on average, followed by defenders, then midfielders, then strikers.

In between the two surveys, in May 2003, Collett had his leg broken by an ‘over the top’ tackle. Following lengthy rehabilitation and an attempt to play at a lowly level in New Zealand and the Netherlands, Collett retired because of his injury and then took legal action against Boro and their insurers.

Collett’s solicitor, Jan Levinson, had become aware of The Independent surveys, and asked if I could summarise the methodology and findings, and explain how the PFA – as a body with access to all contracts – had validated the data. The case reached the High Court in 2008. Witnesses including Sir Alex Ferguson testified that Collett was a major prospect at the time of his injury.

The judge in the case, Mrs Justice Swift, ruled that Collett, without that injury, would have had a decent career as a professional at Championship level or above. “It seems to me that the [2005-06] Independent survey provides the best evidence available about average earnings in professional football and I shall therefore use it as the starting point for my calculation of the claimant’s loss of earnings,” she wrote in her ruling. She awarded a basic £4.3m and said the final sum payable to Collett was “unlikely to be less than £4.5m”.

It was the biggest pay-out ever received in the UK by a professional sportsman for such an injury, and the case garnered significant publicity. Collett went off to study English literature at Leeds University and, now 39, has lived a life away from the limelight ever since.

It wasn’t long before other lawyers sought the unique – and now High Court-approved – data on wages for cases they were working on. I dived deeper into the subject, and over subsequent years obtained much more information – from clubs, unions, and official league sources – not just on basic pay but bonuses and benefits. In the past 15 years, this data has been used in numerous judgments, resulting in awards ranging from tens of thousands to millions of pounds.

By the time I launched a sports business website, sportingintelligence.com, in 2010, I’d expanded my interest in, and knowledge of, player salaries in sports leagues as varied as North America’s NFL, NBA, MLB, NHL and MLS as well as Australia’s AFL (Aussie Rules football) and Japan’s NPB (that country’s top baseball league), as well as Europe’s other major football leagues: Serie A, La Liga, the Bundesliga and Ligue 1.

To accompany the international launch of the website in March 2010, I compiled a review of global sports salaries, comparing per-player pay across different sports, in different countries.

The story went viral: the New York Yankees were No.1 that time, and the top dozen best-paid teams included football clubs from the Premier League and La Liga, multiple NBA basketball teams and even an IPL cricket franchise. To be honest, it went too viral. It featured on the BBC website, it was reported worldwide by Reuters and then by thousands of news organisations and websites.

The story went viral… my goal had been to attract traffic to my new website, and now the volume of visitors had crashed it, for days

My goal had been to attract traffic to my new website, and now the volume of visitors had crashed it, for days.

Since then, I’ve tracked wages across multiple leagues in different sports and countries. Player salaries are typically the biggest single expenditure for any professional sports team.

Leagues that want to promote competitive balance usually have salary controls, whether hard caps or luxury taxes or some other means to stop the richest simply hiring the best all the time. But the elite European football leagues have not had any meaningful salary controls since various iterations of a maximum wage were scrapped in the 1960s. And since 2002, the Premier League has paid the highest average wages, by an increasingly considerable margin.

Had it not been for one bad tackle in a reserve game, Ben Collett would have benefitted from that.

Tomorrow, I’ll tell you a story about some other footballers who lost their careers. But who received nothing.

Hi Ivan. thanks for reading. The judge in the case presented her workings in the ruling, a copy of which is linked in the piece but you can find here: https://www.sportingintelligence.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/Ben-Collett-ruling.pdf

And that ruling was upheld to the last dot and comma when it went to the Court of Appeal. That judgement is here: https://www.sportingintelligence.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/2009-06-17-Ben-Collett-Court-of-Appeal-Judgment-Transcript.pdf

An interesting and very well-researched article.

As an Economist (who once did a few calculations in the USA for loss of earnings) I am intrigued as to how the lump-sum compensation was arrived at: logically it *ought* to be the present value of the stream of lost future earnings, plus any premium for emotional distress etc. Of course, the difficulty in calculating PV would be the choice of discount rate.