What’s a vote worth? How Fifa’s attempt to devolve power could be a bribers’ charter

* This exclusive feature from Issue Three of The Blizzard was offered to SportingIntelligence by the collective of writers at The Blizzard. To read more brilliant and original work from the same collective download Issue Three of The Blizzard which is out now on a pay-what-you-like basis .

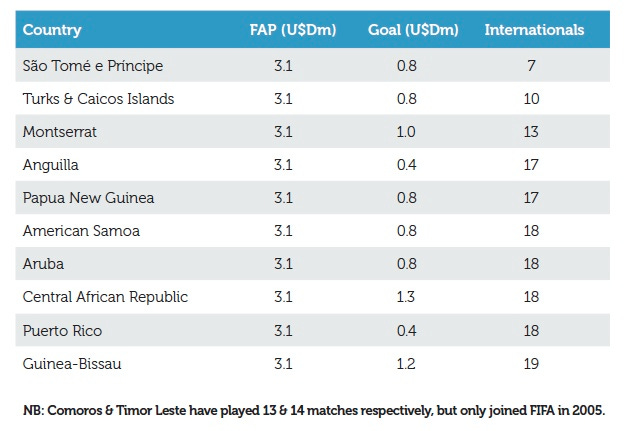

By Steve Menary 6 December 2011 Going by the events at the infamous meeting of the Caribbean Football Union (CFU) in a Trinidad hotel earlier this year, the going rate to ‘buy’ a Fifa vote is $40,000. That, though, could soon change. $40,000 is the sum that Mohammed Bin Hamman allegedly offered CFU members to support his vain attempt to replace Sepp Blatter as Fifa’s president. The Qatari failed and was banned for life, but Fifa’s response to the fall-out from that meeting and the shambolic bid process for the 2018 and 2022 World Cup finals could potentially make corruption more widespread. “We should give more power to the associations,” said Blatter in June 2011. “I want the organisation of the World Cup to be decided by the Fifa Congress. The executive committee will create a shortlist and make no recommendations, only a list, and the congress will decide on the venue.” Previously, the 24 members of Fifa’s Executive committee (ExCo) voted on the destination of the World Cup finals. Those ExCo members have already been shown to be vulnerable to corruption, as was demonstrated by the bans handed out to Nigeria’s Amos Adamu and Tahiti’s Reynald Temarii during the bidding campaign for the 2018 and 2022 tournaments. Now, Blatter is spreading the love. In future, all Fifa’s members will have a potentially lucrative vote on both the presidency and the destination of future World Cup finals, which is an even murkier political process than the presidential election with infinitely more scope for corruption. There is a fine line between lobbying, such as England’s misguided offer to play a friendly in Thailand in return for the Thai ExCo member’s vote in the 2018 World Cup bid process, and dishonesty. That line is often blurred as Germany’s involvement in the sacking of the Philippines’ English coach Simon McMenemy last year showed. In 2006, the Philippines slumped to 195th in Fifa’s rankings and did not even bother entering the 2010 World Cup qualifiers. Shortly after the South Africa jamboree ended, McMenemy took charge and engineered a remarkable revival. Under his guidance, the Filipinos qualified for the finals of the regional Suzuki Cup, in which they beat the defending champions Vietnam and reached the semi-finals. The young English coach’s reward for producing the Philippines’ best-ever international performance was to find out last Christmas via Twitter that he was sacked. His job was given to a German, Michael Weib, in a switch aided by the German Football Association, the DFB. Local reports that the move was coupled by a Teutonic cash injection of €500,000 would have tested that line between lobbying and corruption. The DFB deny any financial aid but, either way, the Germans are likely to expect Filipino support in any forthcoming Fifa ballots. At least that unseemly transaction was made public. Shady dealings at other Fifa members struggling at the bottom of the international rankings often do not. There are places in which Fifa’s audit trail has evaporated, places that test Blatter’s claim that international football has primacy over the club game. Not only has American Samoa never won a game, the US-controlled territory has — despite receiving millions of dollars in Fifa aid since joining the world game in 1998 — never played a home international in Pago Pago. American Samoa has the dubious honour of being on the wrong end of a world record 31-0 stomping from Australia a decade ago. Three years later, the former Spurs player Ian Crook briefly took charge for the 2006 World Cup qualifiers. Three weeks later, having failed to win any of those games, he quit. Asked what his recent charges needed to improve, Crook pointed out that they had nothing in the way of infrastructure: no pitches, no office, no coaching body. Soon after, the Football Federation American Samoa imploded and Fifa despatched a team to take control of the FFAS. Whatever happened, no-one — least of all the FFAS — wants to discuss the problems. American Samoa did enter the 2007 Pacific Games but progress was ended by the tsunami that devastated the islands, killing 31 people. With the FFAS now running properly, Fifa stepped in with $400,000 of Goal funds to rebuild facilities, but American Samoa had not played a single game for four years before returning for this year’s Pacific Games in New Caledonia. Through Goal and the Financial Assistance Programme (FAP), Fifa has established facilities in numerous poverty-stricken associations, but actually playing senior internationals — a major factor in Blatter justifying Fifa’s primacy over the club game — seems beyond some associations. Fifa helped rebuild facilities in Montserrat after the Soufriere Hills volcano erupted in 1995. Islanders were evacuated en masse. Many returned, but Montserrat has not played a home match this century and still has neither a league nor even a club. Fifa’s rules insist that members play in at least two Fifa-accredited tournaments over a four-year period or lose their vote. American Samoa retained theirs by entering a handful of junior tournaments; other Fifa members seem to have no focus on developing their senior sides. Friendly internationals are the bane of Premier League managers but are rarely played by nations at the bottom of the rankings. Turks & Caicos Islands, for example, have not played a friendly international since 2000. Instead, associations sporadically enter senior competitions simply to retain their all-important vote. In the first decade of this century, Montserrat accumulated millions of dollars in Fifa aid yet managed just 13 senior internationals — the same number of games played by the Falklands in the bi-annual Island Games, all in the northern hemisphere and without a cent from Fifa. A number of other Fifa members have proved equally incapable of playing regularly over the last decade despite generous Fifa support, as shown by this table:

Although Fifa does not break down how individual members use FAP, funding senior male internationals was fifth in terms of spending priority for grants distributed between 1999 and 2006, taking up just 14% of funds dished out. Fifa says all members received FAP grants over the last decade, so how can places that get millions of dollars in aid prove incapable of staging senior internationals that locals can aspire to play in? Such a lack of opportunity would test the most patient of players, but no-one surely can be as enduring as the national team of São Tomé e Príncipe, which has not played an international since an 8-0 trouncing by Libya in 2003. Three times a week, the São Tomé squad get up at 6am to avoid the debilitating heat off the coast of West Africa and train, the prospect of a game always tantalisingly out of their reach. São Tomé has received $250,000 a year in FAP funds over the last decade but quite how Manuel Dende, then president of the Federação Santomense de Futebol, spent that money in his dozen years in charge is a mystery. During Dende’s reign of inertia, four national São Tomé championships were cancelled and another merged. Somehow, he never got round to organising another match after that shellacking from Libya. São Tomé eventually lost their Fifa vote and were dropped from the rankings but Dende was only voted out last year. Since his departure, signs of international activity remain an apparition as Brazilian journalist Rafael Maranhão found on visiting São Tomé this summer. Few journalists make the lengthy trip. Surprised at this interloper, the new FSF board told Maranhão that a friendly with Equatorial Guinea was scheduled for July 2011. That was a surprise to the Equatorial Guinea Football Federation, who knew nothing about a fixture that never took place. São Tomé have entered the preliminary qualifiers for the 2014 World Cup. Providing the two-legged pre-qualifier with Congo is fulfilled, the FSF must enter just one more Fifa competition — beach football, futsal, an Under-16 game, anything will do — to get its vote back. With Blatter now offering Fifa’s members not one but two golden eggs that is a task even the lackadaisical FSF should get round to. As Bin Hamman’s offer in the Caribbean showed, voting for a new Fifa president proved lucrative for some greedy, lazy international executives, but securing the right to host a major tournament is a far dirtier process that offers tempting diversions for corruptible executives, particularly those at some nations languishing at the bottom of the Fifa rankings. If Fifa is really serious about countering corruption, there is a solution, a quid pro quo that Blatter could introduce while also opening up World Cup votes to all 208 members. Fifa did not uncover corruption in the bid process for the 2018 and 2022 World Cup bids; the media did. While the Concacaf executive Chuck Blazer turned whistle-blower in the Caribbean, the uncovering of that shoddy affair was greatly aided by the press. Greater transparency is clearly needed. If all 208 members were forced to publish freely available annual accounts, that might provide answers. History, though, suggests we shouldn’t expect such a move anytime soon from Blatter or Fifa’s hermetic executive. .

Edited by Jonathan Wilson, Issue Three of The Blizzard is out now and features articles by a host of top writers including Philippe Auclair, Gabrielle Marcotti, Simon Kuper, and Michael Cox. The Blizzard is a 190-page quarterly publication that allows writers the opportunity to write about the football stories that matter to them, with no limits and no editorial bias. All issues are available to download for PC/Mac, Kindle and iPad on a pay-what-you-like basis in print and digital formats. . . . Sportingintelligence home page More on Fifa Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter