What are Man City really worth to sponsors? The answer could be fascinating ... and cast previous deals in a bad light

Ensuring any extension of their partnership with Etihad complies with rules may highlight the inflated nature of previous sponsorship packages

Manchester City are in the process of extending their most important and lucrative sponsorship deal, with Etihad; and to make sure any such deal isn’t challenged by the Premier League, it makes sense for City to seek external guidance on the maximum ‘market rate’ they can attract from the Abu Dhabi-based airline.

The new annual figure will be doubly fascinating, both as an indication of what City are really worth to sponsors these days, but also in highlighting how absurdly high their deal was with Etihad a decade ago.

This is the conundrum City face.

They need to maintain or increase current revenues while staying within the rules. Independent market validation may assist that.

But 2024 “market rates” will be compared to previous deals between City and Etihad, not least a major deal done in 2011.

That 2011 deal was barely defensible back then, yet we now know within two years it had doubled; such anomalies contributed to “the 115 charges”.

The new deal is likely to be shrouded in secrecy. Since signing a 10-year, £350m-plus-bonuses deal with Etihad in 2011 that included sponsorship of City’s shirt, training campus and stadium naming rights, the club have never publicised any of the multiple renewals in the years since.

In fact, those renewals are only known about at all because basic details were disclosed in court papers when City appealed to CAS in 2020 against a two-year Champions League ban for breaking UEFA FFP rules.

The pending extension comes at a time when City are reportedly threatening legal action against the Premier League for changes to rules in place around commercial deals between related parties.

The changes on associated party transactions (APTs) were approved by Premier League clubs a week last Friday, with the clubs having been informed that approval may lead to a legal challenge from City.

The threatened legal action comes, in turn, as City face the outcome of 115 Premier League charges made against them in February 2023. Those charges fall into five broad categories between 2009-10 and 2022-23: of providing inaccurate financial information; of not declaring all payments to a manager and some players; of not complying with UEFA’s FFP rules; or with the Premier League’s own financial rules; and of not cooperating with the Premier League’s investigations from 2018-19 to 2022-2023 inclusive. A date for an independent hearing has been set but the date is not public. It has been reportedly slated for autumn this year.

It makes sense for City to seek expert industry input on future Etihad deals, so that Etihad cash can continue to flow. Similarly, the Premier League will use external advisors to check that clubs’ major deals are at ‘arms length’ market rates, and not inflated. The tweaked rules aim to prevent owners effectively topping up their income unfairly.

The Premier League’s 2023-24 official handbook, available via this link, sets out in Appendix 18 (from page 597 onwards using the numbers at the bottom of the pages), the precise ‘Fair Market Value Assessment Protocol’.

I won’t bore you with all the details – there are pages of detail in the handbook if you want them – but elements considered include the tier of partnership, assets and rights delivered by the club to any sponsor, media exposure, market trends and, “in respect of the club”, its social media following, geographic spread of fanbase, playing success and track record on “delivering returns on partner investment”, among other things.

So, let’s start with what City are offering Etihad in the extended deal: it’s the same as now - front-of-shirt sponsorship for the men’s and women’s teams, sponsorship of the club campus, and naming rights for the stadium.

How much is that all worth per year to Etihad in an arms-length deal, now and in the near future? At the very least, it is worth more than €70m a year (£59.8m a year), using Barcelona’s 2022 Spotify deal as a benchmark, while another industry source thinks the total could creep as high as £100m per year.

I asked the sponsorship valuation experts at Turnstile if they could talk me through their own valuation of this deal. They list Manchester City among their clients (past or present) on their website.

In April 2022, Turnstiles’s then CEO, Dan Gaunt, demonstrated his company’s software in public at the SportsPro Live conference to show how he reckoned Chelsea’s next shirt sponsorship should be worth £43.4m.

As detailed in this report of that presentation: “The final amount was calculated based on the cumulative value of benefits such as hospitality, social media and activations, as well as brand exposure on apparel, signage and media backdrops, in addition to intellectual property (IP) rights.”

Turnstile break down every component part of a deal and assign a financial value to it. They break this down into three categories: ‘Direct benefits’, ‘Exposure’, and ‘Intellectual Property’ or IP.

Direct benefits might include match tickets or even a hospitality box to entertain clients, some signed merchandise, a few ‘meet & greet’ days with players, some digital ads on pitch side hoardings, and a set number of social media posts.

The ‘exposure’ element is the value of any branding that is purposefully positioned to be picked up as part of a television broadcast; this might include the sponsor’s name and logo on the stand, and some presence on the post-match interview backdrop. A calculation is then made depending on the number of seconds of airtime these get across a season, multiplied by eyeballs. Turnstile use a global viewing database and a ‘signage buy’ rate to work out how these seconds translate to cash.

The IP element is a figure that takes into account two things: a club’s global fanbase, and how that compares to similar clubs with existing naming rights deals in similar markets.

I asked Turnstile last week if they could run the numbers for City’s current shirts (men and women), campus and stadium rights. They replied: “In accordance with confidentiality agreements within the Premier League, we are unable to provide any comments or information regarding your request.”

It’s worth pointing out that the Premier League, when assessing future deals, will be using their own external experts. Maybe they’ll use Turnstile so that’s why they couldn’t help me. I don’t know.

But let’s have our own stab at trying to put a ballpark figure on what Etihad might pay per year from now on. First, the single most valuable part of the deal: the men’s front-of-shirt. Below are the current top 10 most valuable shirt sponsorships per year in global football.

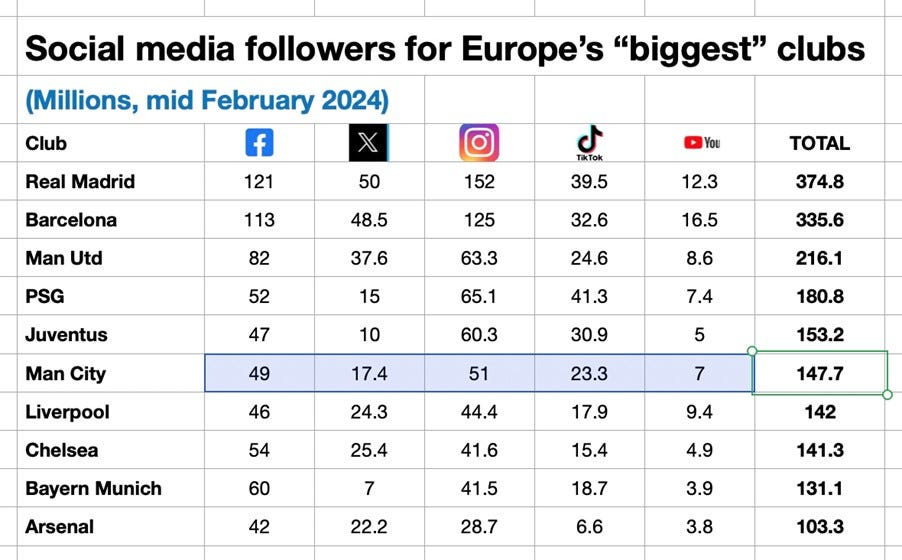

And before we consider what City might now attract for this, going forward, here’s a quick and simple gauge of the global popularity of Europe’s ‘biggest’ clubs. Of course, this has limitations, but social media is an obvious barometer of popularity given that it costs nothing to follow any club on Facebook, X, Instagram, TikTok or YouTube.

On this basis, six clubs in Europe are more popular than City, with Real Madrid and Barcelona considerably more so, Manchester United almost 50 per cent more popular and PSG tens of millions ahead. City reside in a similar district, popularity-wise, as Juventus, Liverpool and Chelsea.

I don’t believe it’s possible for City to argue they are as popular as Spain’s two biggest giants or indeed Manchester United. But it is possible they can argue that, as recent European and world champions, and as the No.1 team in the world in most ranking systems – whether that’s produced by Gracenote, or UEFA, or ELO – that their shirt could be close to No.1, or at No.1 in value.

Premier League clubs can also point to evidence that the PL is the most popular sports league in the world (see pages 20-25 of the report linked here), and with the most eyeballs. Being in the Premier League, in and of itself, brings a premium to sponsorship deals that most clubs in most places can’t claim.

Depending on what other assets come with the shirt – tickets, hospitality, VIP opportunities, promotional hours with star players – you might even be able to argue the City men’s shirt is now worth £65m a year, or thereabouts.

I’m not saying it’s set in stone. But it’s arguable.

The women’s shirt? Not so much. The best women’s team in the world over recent years are FC Barcelona Femení, winners of two of the last three women’s Champions Leagues and runners-up in the other, and eight-times winners of their domestic title since 2012. Barca Femeni’s biggest front-of-shirt deal was worth £3m a year.

Manchester City women last won the Women’s Super League in 2016 and have mostly flopped in Europe. I don’t think there’s any case for a front-of-shirt deal worth above a low single-digit millions figure, for now.

Which brings us to the campus / training ground sponsorship, which at many clubs comes twinned with sponsorship of the training kit. Manchester United have done deals worth between £22.5m and £24m per year with AON and Tezos respectively over the past decade. Arsenal’s new training ground sponsorship deal with Sobha Realty is reportedly worth “more than £10m a year”. Barcelona used to have a training-kit deal with electronics firm Beko worth around £19m a year.

It wouldn’t be ridiculous for City to claim their campus and training kit rights might be worth £20m per year or slightly more, using the other clubs as benchmarks. Again, not set in stone, but arguable.

One hiccup may come for City in proving to the Premier League (see Appendix 18 of handbook, link above) they have a track record on “delivering returns on partner investment”. No doubt those conversations will get niggly.

Which just leaves stadium naming rights, arguably the most contentious part of the package. When Barcelona struck their four-year deal with Spotify for the music streamer to sponsor Barca’s men’s and women’s shirts, training kits and stadium for four years from 2022-23, the entire four-year package was reported as worth €280m, or €70m per year – approximately £60m a year at current exchange rates. And the naming rights element, according to business journals in Spain, was worth a nominal €5m per year of that.

City will almost certainly argue that Barca accepting so little was a sign of a cash-strapped club accepting any big number in a post-Covid financial storm that forced them to let Lionel Messi and others leave because they could no longer afford them. And there may be some justification for that.

So, what are naming rights to City’s stadium worth now? This really is contentious because stadium naming rights in football have always been low, not least in Britain. Take the 30 largest football grounds by capacity for example, and most, or 24 of 30, have no sponsor, from Wembley to Old Trafford, to Anfield, St James’ Park, Villa Park, Goodison, Bramall Lane, Molineux, Ewood Park and Carrow Road, to name just 10 across the spectrum.

Being generous, let’s say that City’s stadium naming rights are worth more than the other contender for most valuable – Atletico Madrid’s Wanda stadium, new in 2017, where the sponsorship is worth around £8.4m a year.

Let’s say the men’s shirt is in fact more valuable than Real Madrid’s, at £65m, and the women’s shirt is worth more than Barca’s, at £5m, and the campus is worth £25m, and the stadium is worth £10m. That might, at a push, get you an independent valuation for Etihad to sponsor all those elements at about £105m a year, today. My best guess is that’s the ballpark Etihad and City will try to get past the Premier League. I would also guess there might be some pushback, with quibbles around the odd few million pounds. I still don’t think it will be far off £100m a year.

So far, so simple.

One problem for City in this regard is that when they announced their 10-year deal with Etihad back in 2011, the club struggled to argue, with any credibility, that they could justify getting £35m per year (plus bonuses), given that they hadn’t won a league title since 1968 and had never played in the Champions League.

As I wrote at the time in August 2011: “That figure caused a stink among some of City’s rivals, including Liverpool and Arsenal, as they asked how on earth this could be justified. Etihad, after all, is an airline with family links to Sheikh Mansour.

“As such, there have been suspicions of a ‘mates rates’ deal, that Etihad have paid way above the ‘going rate’ as a favour to boost City’s coffers, to help City move towards break-even point – and hence not fall foul of FFP.”

But then I took a call from someone senior at City who tried to make the case that £34m-a-year was defensible, just about, or might be, by the end of the 10 years, if City by then were winning titles and rocking it in Europe.

OK, I said, I’ll take another look at the numbers, and I concluded they might – just – be right, so I wrote this piece on Sporting Intelligence.

This is probably a good time to remind City fans that I long had a good relationship with lots of people at City, back to the Maine Road days. They knew I was a fair and objective reporter, big on data and proof. City and Sporting Intelligence partnered on a data project. We showcased their academy / campus when it was announced. I got to know City legend Bert Trautmann when writing my first book and wrote about the club’s glorious history of accepting foreign players.

I was invited as chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak’s guest to City’s executive suite, and met directors and other senior staff, who I would discuss FFP with, and in some cases stay in touch with for years. When Sporting Intelligence was winning awards as the best independent sports website, City staffers were among those cheering loudest. Crazy, eh? Yet true.

If you’re a City fan and want your cognitive dissonance to go through the roof, how about the realisation that in February 2014, the massively pro-City fanzine Bitter and Blue, was quoting me extensively as an authority on City’s finances and sponsorships.

So, my coverage of City and FFP especially since 2014 isn’t inspired by a rabid anti-City agenda. It’s based on knowledge of the club and their finances, inside out. It’s based on people I knew and know, who worked there or still do. I knew City would fail FFP and wrote as much as long ago as 2011. “It is inevitable City will fail to meet the first FFP break-even target in 2013,” I wrote, unequivocally. “The question is by how much, and whether City can use loopholes to escape punishments likely to involve fines at least, and theoretical bans from Europe at worst.”

Fines and potential bans were an avoidable fate for City but they kept on spending, because they felt entitled to, and felt the rules were not for them.

By the time City started filing strange accounts and no longer wanted to try to explain stuff – whether involving staff disappearing from the club’s books or tens of millions of pounds of dodgy sales of intellectual property – my job as a journalist was to keep asking questions. Uncritical coverage, as a result of historic good relations, isn’t journalism. It’s a dereliction of journalism.

Anyway, back to that £340m, 10-year deal (plus bonuses). It was, just about, defensible in a long-term context. But guess what? By 2013-14, or inside 29 months of the £35m-a-year deal being signed, it was, by December 2013, worth, erm, £67.5m a year.

The men’s shirt element alone was being considered internally as worth £35m a year, at a time when the biggest shirt deal in English football was Arsenal’s new £30m-a-year deal, while Manchester United and Liverpool’s shirts were worth £20m a year. Yet Manchester City were briefing in summer 2013, as they had in 2011, that the men’s shirt element of their deal was worth £20m a year.

Every summer on Sporting Intelligence from 2010 onwards, myself and my colleague Alex Miller would compile a list of Premier League shirt deals, sourced via the clubs and sponsors. Alex and I would contact every club, every year, to check numbers. At City over many years since, we’d check directly with a commercial figure such as Omar Berrada and / or a trusted PR like Toby Craig or other senior comms person. Alex made the call to City that year and was told the shirt deal was worth £20m in 2013-14, as we reported.

The other elements of the Etihad deal that had ballooned by December 2013 were campus rights, by then worth £17.5m and stadium naming rights, at £15m per year. That last figure – and we didn’t know any of these numbers until years later, via Spiegel’s Leaks – was especially jaw-dropping. Back in 2011, I took industry soundings on what City’s naming rights might be worth annually, at best, and the figure was £5m.

Yet by December 2013, it was up to £15m-a-year, a sum that would in in fact have been the most lucrative naming rights deal in the whole world, in all of global sport. On an annual basis, that would have put it ahead of the New York Mets’ Citi Field (then worth £12.5m a year), the Dallas Cowboys AT&T Stadium (£12.5m a year), The MetLife Stadium of the New York Giants and Jets (£10m a year) and the San Francisco 49ers Levi’s Stadium (£6.9m a year).

Which is, by any measure, ridiculous.

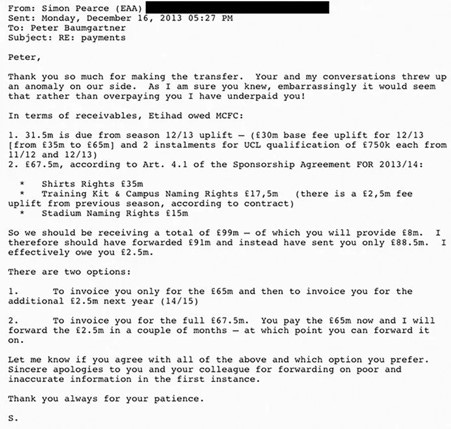

Anyway, here’s an email detailing the £67.5m a year that City were accepting from Etihad not so very long after knowing that £34m-a-year was stretching credibility. The same email, from Simon Pearce — a key advisor to Sheikh Mansour and the Abu Dhabi government — to former CEO of Etihad Airways, Peter Baumgartner, also details how Etihad would apparently supply £8m of a total of £99m due to City, from Etihad.

There will be some Manchester City fans who will look at any Spiegel document and claim it’s fake. The document above isn’t fake. And in any case, by the time of CAS’s judgement to overturn City’s two-year Champions League ban, it was a matter of record in the ruling that the 2011 Etihad-City sponsorship agreement was upgraded before two years of the 10-year deal were even up. This version was called ‘Etihad 1’ and was dated July 2013 but “effective from 1 June 2012”.

‘Etihad 2’ was another upgrade, dated 21 August 2014, while 'Etihad 3’ was dated 23 November 2016, effective from 1 June 2015; 'Etihad 4’ was dated 23 November 2016. The same CAS documents showed that in three seasons after 2012, Etihad paid City £220.575m, or about £73.66m per year. Which is somewhat bigger than the £34m a year that was being criticised as indefensible by many in 2011.

I don’t know – and neither does anyone outside the process – the precise details of the 115 Premier League charges that relate to City allegedly providing inaccurate information in relation to sponsor deals. Did they tell the Premier League every time they re-upped the 2011 deal, and did they declare the true sums? In time, hopefully, all will be explained.

And clearly, as clubs including City turn to external agencies to defend any future deals or extensions, they’ll want to make sure they don’t fall foul of the current rules. The Premier League is cracking down on this stuff not to “get” any particular club, but to try to maintain basic fairness.

Of course, I asked both City and Etihad about these events. Here are the questions I sent to both of them last Wednesday.