The final frame: 40 years on from the greatest denouement in Crucible history

Most Britons under 50, and most people on the planet, probably can't comprehend why 33% of the UK were watching snooker on TV past midnight in 1985. Here's why.

The 2025 snooker World Championship starts tomorrow at the Crucible Theatre in Sheffield and if you follow it in even the most minor way you won’t be able to avoid non-stop references to the 40th anniversary of the 1985 final.

To say it was one of the most famous and dramatic sporting occasions in the history of British sport - and certainly televised sport - is not hyperbole.

The bare statistics of the TV audience remain jaw-dropping. The denouement happened at gone midnight and was screened on BBC2. The TV audience still watching live at that point, in the first hour of Monday, was 18.5m people, or 33% of the UK’s population at the time.

It was a record for BBC2 and remains so four decades later.

It was the largest post-midnight audience for any programme on any channel in the UK, and remains so.

Snooker as a mass-market sport reached its peak that night, in one match, in one frame (the 35th of 35), with one ball all-important in the end. After two days of action, it was all about the final black.

That final pitted the world No1, Englishman Steve Davis, 26, already a three-times world champion, against Dennis Taylor, a 36-year-old from from Coalisland, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland.

The high point of Taylor’s career until then had been as the loser in the 1979 final, and by 1985 he was arguably best known as the bloke who wore “upside down” glasses specially designed for playing snooker, and for his entertaining banter on the exhibition circuit.

Sixteen years ago, and 24 years after it happened, I was asked to write a long-form piece about it for a special series in The Independent about great British sporting moments.

I spoke to Taylor and Davis, and to Taylor’s mentor during that pinnacle of his sporting life.

I spoke to people who had been there, and, needing to remind myself of the mechanics of the fateful final frame, I ordered a DVD of it and watched it multiple times. (YouTube and iPlayer were not yet places you could just go and find clips, let alone the whole thing).

It’s hard to exaggerate the extent to which snooker was pre-eminent as a TV sport in 1985, due to a coalescence of cultural and social trends.

Football, the national sport, was heading to its lowest ebb, ravaged by hooliganism, blighted by dreadful facilities, and unattractive to fans tired of being herded into cages. The average attendance in England’s top football division in the 1983-84 season had been a post-war low of 18,856. (It’s currently above 40,000 per match on average).

By the start of the 1985-86 season domestic league and cup football in England wasn’t shown at all on terrestrial TV.

Snooker was a relatively cheap and easy way to fill hours of airtime with feel-good figures. It had surged in popularity thanks to maverick tabloid mainstays such as Alex "Hurricane" Higgins and Jimmy "The Whirlwind" White. When they weren't playing, they were drinking, shagging, gambling - or getting up to mischief.

Then there was Cliff Thorburn, the Canadian heart-throb with a moustache to match anything that Hollywood's Tom Selleck could muster.

Another Canadian, Bill Werbeniuk, who got as high as No8 in the world rankings in 1984-85, was famous for his alcohol consumption, including during matches. He was reported to drink up to six pints before a match then one more pint per frame. He was reputed to have drunk 76 cans of lager during one match in the 1970s.

A year after the Taylor-David “Black Ball final”, both of them along with other players and Cockney pop rock duo Chas & Dave reached No6 in the British singles chart with the song “Snooker Loopy.”

And yes, this did all actually happen.

The first prize at the Crucible in 1985 was £60,000, among the biggest pots in any individual sport at the time. The runner-up earned £35,000. Snooker wasn't just at its zenith, but was centre stage on TV in an age when home computers were rare, mobile phones were virtually non-existent, and Google, Twitter and texting were all decades away.

Britain had four TV channels, with the youngest, Channel 4, in its infancy. What could a family do together on a Sunday night? Watch television. The biggest weekend TV shows were That's Life, The Two Ronnies, Last of the Summer Wine and Open All Hours - and, for one amazing weekend, the World Championship snooker final.

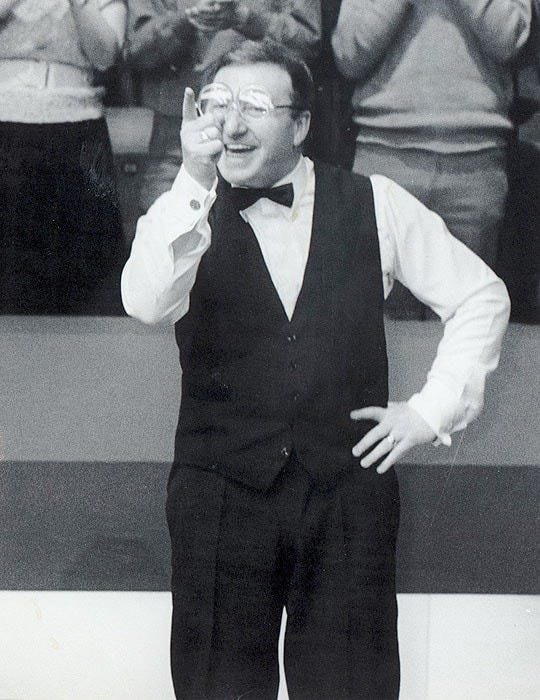

When Taylor eventually completed his victory, he wagged his finger at someone in the crowd (below) before planting a kiss on the trophy.

Taylor, years later, told me that he was signalling to his “good mate”, Trevor East, who had effectively played the role of Taylor’s sports psychologist over that fateful weekend. "He was with me throughout the whole championship,” Taylor told me. “That finger wag said: 'I told you I'd do it’."

East told me: "The end is indelibly etched on my memory, it was one of the greatest moments."

Their partnership is not the only aspect of the final that remained widely unknown for many years, and perhaps even today.

East was then the executive producer of ITV's snooker coverage. He'd hired Taylor, a top player, as a commentator, and the pair had become close friends.

East's background included reading the sports bulletins on Tiswas, the anarchic Saturday morning kids' TV show of the 1970s and early 80s. His future included being the kingpin of sport at BSkyB as it become the major player in pay-TV, and later the director of sport at Sky's ill-fated rival, Setanta.

The 1985 final, the best of 35 frames, started at 2pm on Saturday, 27 April. Davis, youthful and pale, his thick red hair plastered flat over his head, wore a dark blue waistcoat, a pale blue shirt and a dark maroon tie with spots. Taylor was dressed in a pale pink shirt, light grey waistcoat, and a grey tie with pink diagonal wavy stripes.

In a masterful first session, Davis took a 7-0 lead. That session was the only one in the final when East wasn't in attendance to support Taylor. He was a director of Derby County at the time. They had a Third Division match that Saturday, at home to Cambridge United, and East needed to be at the Baseball Ground.

"As soon as the game ended, I turned on the telly and saw the score in Sheffield," East told me. "I just thought 'shit', jumped in my car and sped 40 miles up the M1.

“Dennis and I got on so well. He would often lose focus and concentration, and had a tendency to get downhearted about the smallest things. I don't know why, but I used to be able to press the right buttons in him somehow."

After losing the first frame, Taylor was relaxed, chatting to supporters near his chair at the bottom left-hand corner of the table. At 7-0 down, he was reduced to fidgeting. "I wanted a hole to open up and swallow me," he told me.

Davis won the first frame of Saturday evening, for 8-0. Taylor clasped his hands together. "The determination and fight was there," he said. "I was 36 years of age at the time, and I knew that this would probably be my last chance."

In frame nine, Davis missed a green. "Maybe I relaxed a bit," he said. Taylor came to the table and snatched the frame, for 8-1. It was 8.15pm. By the end of Saturday night, Taylor had clawed back to be trailing 9-7.

The protagonists retreated to their lodgings. Knowing he would struggle to sleep, Taylor ordered a bottle of champagne from the bar of his hotel, The St George, outside Sheffield, and shared it with his wife, Trish, and with East.

The next morning, there was no hangover, nor much thought of Davis. "The hotel had a lake and I spent some time walking around it, looking at the ducks, thinking about my Mum," Taylor told me. His mother, Annie, 62, had died suddenly the previous October from a massive heart attack.

"Foremost in my mind wasn't really [that] I was trying to beat Steve Davis, the greatest player in the world. It was my Mum. I'd been in one final before, in 1979, and a friend had flown Mum over for that. I'd led into the final day, I should have done better."

Back at the Crucible on the Sunday, the score moved to 11-11, and by late evening, with families everywhere gathering around the box, to 17-15 in Davis's favour.

The sponsors were in the wings with a cheque. Taylor kept them waiting by pulling back to 17-17. The 567th and final frame of the tournament started at 11.15pm.

Davis broke off, superbly, leaving the white tight on the bottom cushion. "I was in all sorts of trouble already," said Taylor. He missed: 4-0 to Davis. Taylor had never been in front during the entire match. He never would be, until the last ball was down.

It took four minutes before another error by Taylor allowed Davis in for a red. "The balls were in horrible places already," said Davis.

Most of the reds were in a bunch towards the top left corner. The colours were off their spots. There had not been a single century in the whole final and there certainly wouldn't be one now.

Davis potted a green and a red for a break of five and 9-0. Taylor potted a stunning long red, but could build nothing: 9-1. Minutes passed. He managed another red: 9-2. After 20 minutes, and errors on both sides, the score had only reached 13-7.

Taylor surveyed the table, and fiddled with his ear. "One bad mistake then and it would be the end: of two days' work, two weeks' work, and in my case 13 years of waiting to win the title," he told me. "The championship would have been all out the window."

Davis made a bad mistake, leaving a red. Taylor took advantage, hitting a break of 22 for a 29-13 lead. But he ran out of position and had to play safe.

He walked back to his chair, staring high up into the crowd. "I was looking up at the gods there, thinking: 'What a golden opportunity just went by'."

Davis potted a red and blue, but lost position. He leant on the table with both hands, then tried a red with the spider and missed: 29-19. Taylor tried a red and went in-off: 29-23. Davis potted a long red, but missed a blue: 29-24. "You can only put that down to carelessness, which it wasn't, or pressure," Davis said. "There were a lot a chances going begging."

On and on the torture went, the volume of gasps and groans in the auditorium increasing as they were in homes across the nation. It was midnight. The frame was 45 minutes old, and Taylor was 44-28 ahead. He missed another red, allowing Davis in with a plant to the top right.

"Steve realised this was a chance and I could barely look,” Taylor said. “I'd spent three quarters of an hour building a lead of 20 points and in minutes it was going to be gone."

Davis potted blue, red, blue - at which point Taylor's head dropped as he waited for the kill - then red, blue, red, blue, red. But then he ran out of position and played safe, hiding the white.

Taylor fouled trying to escape. Just the last four colours remained, worth 22 points, while Davis had a lead of 18, at 62-44. Davis, in effect, just needed the brown. Taylor needed everything.

Davis tries to cut in the brown. It rattles the jaws of the pocket and stays out. Davis shakes his head. Taylor mouths something indiscernible. Taylor misses the brown. The crowd gasps. Davis leaves it on for Taylor, but it's a narrow cut. Taylor pots it. "Best shot of the tournament, I thought he'd play it safe," says Davis.

"I thought, 'I'm not going to lose the tournament playing a safety shot that goes wrong'," says Taylor, who potted the blue and pink. It was 62-59 to Davis, with the black left and Taylor still at the table.

Taylor tries to double the black to the middle. He misses, but it runs safe. Davis plays safe. Taylor wipes his hands with a towel for 20 seconds, then tries an audacious table-length double. He misses.

Davis tries a double, and misses.

The white is near the top right pocket, the black 3 feet away and the obvious target pocket, the bottom left pocket, 9 feet further on. Taylor misses, leaving the black, cuttable, over the top right pocket. Davis overcuts it.

Taylor comes to the table. He eyes the black, not far from the top right pocket now. He pots it.

He raises his cue above his head. He shakes Davis's hand and the referee's. He shakes his cue, then thumps it on the floor, twice. A fan runs up and embraces him. A second tries to. The referee stops him, but Taylor shakes his hand anyway. Davis nods to himself and sits down.

Taylor puts his cue on the table, his face disbelieving. Then he wags his finger, folds his arms, tip-toes to the trophy, and kisses it.

Interested in more snooker, and one of the most controversial episodes in the sport in recent decades? Then try this.

Brilliant article!