A doping conundrum: just $6m a year on developing new tests, $350m on testing

*

By Roger Pielke Jr

21 July 2014

Speaking last week in Australia, the winner of the 2011 Tour de France winner, Cadel Evans, claimed that professional cycling today is cleaner than at any time in his experience. The 37-year-old Aussie rider said: "It's in the best shape – maybe not economically – but the best shape ethically and sporting-wise that the sport has ever been in, certainly since I've been involved in the sport."

Yet on that same day Team Sky, who employ the past two Tour winners in Bradley Wiggins and Chris Froome, announced that they had parted ways with one of their team members, Jonathan Tiernan-Locke, following a suspension for doping by the International Cycling Union (UCI). The alleged violations are said to have taken place prior to Tiernan-Locke joining Sky. But it adds to a growing list of allegations surrounding the “squeaky clean” reputation of Team Sky.

If road cycling's self-proclaimed cleanest team has a range of issues to face, then what of the wider sport?

How can we really know if the Tour de France is indeed in better shape today than in past years? Are the anti-doping regulations trustworthy? Better data and independent analyses can help to shed some light on these questions.

We know that doping was endemic in the Tour de France through much of the 1990s and 2000s thanks to years of investigation by investigative reporters and the claims of whistleblowers. But it wasn’t until the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency (USADA) released its report on the allegations surrounding seven-time Tour winner Lance Armstrong that the Tour’s recent doping history became widely accepted.

Article continues below

With the advantage of this hindsight, in the graph above we can see the effects of the availability of Erythropoietin, better known as EPO, starting in the early 1990s in the Tour de France. (The data comes with the usual caveats.)

The graph shows the climb times of l’Alpe d’Huez, one of the most famous ascents of the tour, which has been included in the Tour in most years. From 1994 to 2008 the fastest time each year averaged some four and a half minutes faster than the average winning time from 1977-1993. One might think that such a remarkable and sudden increase in speed would have raised some eyebrows. However, tracking performance times by Tour riders has never been made particularly accessible by the Tour or the UCI.

Doping in sport refers to the use of prohibited, performance-enhancing substances by athletes. For the Olympic sports, which include international cycling and the Tour de France, doping violations are identified by the World Anti-Doping Agency and its partners (including USADA). Specifically, according to WADA doping occurs when two of the three criteria are met: (a) a substance potentially or actually enhances athletic performance, (b) the substance poses a health risk to the athlete, and (c) use of the substance violations what WADA calls “the spirit of sport.”

Each year WADA creates a list of banned substances which it deems to have met these criteria. Doping is thus a procedural violation of very specific rules governing competition.

Oversight of doping is such a shared value in sport that 176 countries have signed on to the UN’s International Convention Against Doping in Sport. For instance, USADA is recognized by the US Congress as the non-governmental body responsible for fulfilling the US obligations under the treaty. USADA receives about $10 million per year from the US government.

With doping deemed so important internationally and nationally, it is fair to ask why it took so long to catch Lance Armstrong and others who broke the rules. This is especially a question worth asking given the huge step change in performance, as shown above. The data seem to suggest that something fairly obvious was going on in the Tour de France starting in the early 1990s.

Others have looked at performance data and concluded that other performances, still on the record books, were the result of doping. For instance, Le Monde has raised questions about the “mutant” performances of Miguel Indurain in the 1990s. The only riders who ascended Alpe d’Huez faster than Indurain in the Tour were Armstrong, Jan Ulrich and Marco Pantani, each of whom doped.

But “mutant” times, by themselves are not sufficient to prove a doping violation. Doping is so difficult to detect and to reduce for at least three reasons.

First, performance data is not definitive of violations of the WADA list. In athletics, records are of course broken all the time. It would be a shame if every record-breaking performance was clouded by speculation and allegation of doping violations. But this is exactly what happened when Ye Shi-Wen, a Chinese swimmer, won the Gold medal in the 400m IM at London 2012, and in the process shaving five seconds off of her personal best time. At the time Ross Tucker, a sports scientist with expertise in human performance, wrote “don’t shy away from the question just because it’s politically incorrect – look where that got sport before.”

While Ye Shi-Wen never failed a drug test or otherwise was shown to break any rules, there is some valuable data to be gleaned from looking at performance data for evidence of doping. That is the argument made by Simon Ernst and Perikles Simon of Johannes-Gutenberg University in Germany in a recent paper.

They argue that the signature of EPO can be seen in the top 20 times run each year in the men’s 5000m race. The chart below shows a dramatic improvement in times from 1991 to 1996, what they call “the EPO effect.” They also claim that “the introduction of EPO testing in 2000 led to significant increases in running times.” The subsequent release of a new EPO test in 2008 is also accompanied by an increase in race times. They caution however that “the concrete connection with doping can only be made by assumption or in retrospect.”

Article continues below

A second reason why doping is so hard to detect and reduce is that dopers are one step ahead of their pursuers. Simon explains that drug testing, to identify doping, is fraught with loopholes. For instance, while anabolic steroids are readily detectable, other substances like EPO, human growth hormone and testosterone can be administered at levels which enhance performance, but are not detectable by current methods.

This raises a difficult set of questions – if a violation of the WADA regulations occurs but cannot be detected by contemporary drug testing methods, should it be on the WADA list in the first place? Alternatively, how long do we want to keep testing samples in hopes that future scientific advances can be used to detect violations which were undetectable at the time of the event? Even more perplexing, how should we think about performance-enhancing substances which were once used but later added to the WADA list (or vice-versa)?

There are no easy or unambiguous answers to such questions, but they do need to be dealt with, as the search for performance enhancement, whether allowed or prohibited, is not going away.

For instance, in a survey conducted by WADA of more than 2,000 elite track and field athletes, 29 per cent at the 2011 World Championships and 45 per cent at the 2011 Pan-Arab Games admitted to the use of prohibited performance enhancing drugs. This contrasts to a detection rate of only about 2 per cent for the drug tests used to detect doping.

Perikles Simon explains that this disparity between anonymous admission and formal dtection is partly due to the fact that only about $6 million per year is spent on developing new tests, in contrast to $350 million spent on giving drug tests.

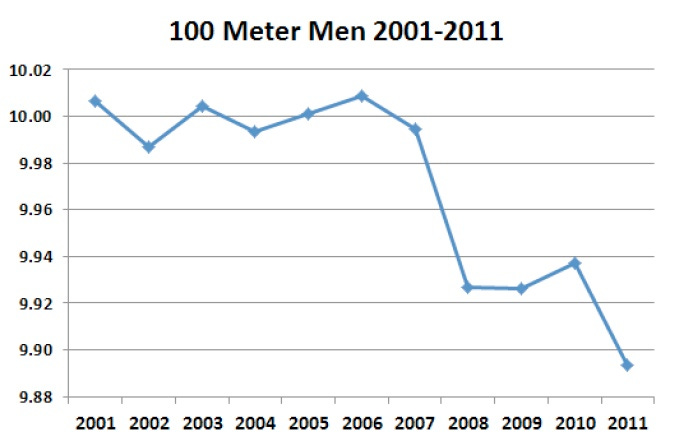

Ernst and Simon also looked at men’s 100m times and identified a large reduction in times from 2006 to 2011 (below, they found a similar improvement at 200m, not shown here). They speculate that the improvement is due to the introduction of Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 (IGF-1) into the medicine cabinet of sprinters: “In our opinion, IGF-1 is the source for the most recent improvements in male short-distance running.” Over this time period the use of IGF-1 was not detectable. They are careful to observe that there are other possible explanations, such as the use of other drugs or different populations and training of athletes.

Article continues below

A third reason for the difficulty in detecting doping is that sports governance bodies may not want to hear bad news, and thus have an incentive to downplay or even cover up doping violations. The UCI, which oversees cycling, is in the midst of a year-long investigation to assess the agency’s poor performance, and perhaps even corruption, during the Lance Armstrong era. The UCI has been accused of covering up a drug test that Armstrong failed, of taking a bribe and of having its leadership financially involved with Armstrong’s team.

In another example, the WADA survey mentioned above was surrounded by controversy when WADA tried to halt its release over the objections of the researchers who conducted the study. Richard Pound, a former WADA chairman, explained: “There’s this psychological aspect about it: nobody wants to catch anybody. There’s no incentive. Countries are embarrassed if their nationals are caught. And sports are embarrassed if someone from their sport is caught.”

One thing we can be sure of -- doping in sport is here to stay. An important question for athletes, fans and those who oversee the games is, how much effort should be spent to root out doping? This question lead to some complicated issues that go well beyond just sport. For instance, how do we balance the rights of athletes to privacy and due process while also implementing a more rigorous and some say already too rigorous) regime of testing?

The Tour de France provides a window into a complex world of human enhancement, global governance and the desire to excel, sometimes at all costs. While the Tour may indeed be cleaner that it’s been in a generation, as Cadel Evans alleges, the questions surrounding how to handle doping in sport remain as vexing and unresolved as ever.

.

Roger Pielke Jr. is a professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado, where he also directs its Center for Science and technology Policy Research. He studies, teaches and writes about science, innovation, politics and sports. He has written for The New York Times, The Guardian, FiveThirtyEight, and The Wall Street Journal among many other places. He is thrilled to join Sportingintelligence as a regular contributor. Follow Roger on Twitter: @RogerPielkeJR and on his blog . More on this site mentioning doping Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter