The CWC: heat on FIFA, MCOs, journalist deaths, Samba style, stadium slogs & more

Ten days into the controversial Club World Cup, Sami Kunti sends this special report from the USA on how the tournament is unfolding on the ground, for better or worse

By Sam Kunti in New York

At long last, the tournament that nobody wanted - except for Gianni Infantino, the Brazilians and the rest of the world - is in full swing.

For this reporter, it means $50 lodgings in East Harlem and a steady diet of pastrami sandwiches, soda and complimentary cookies in the press box. The perfect fuel then for a slog on the East Coast, attending matches at the dreaded MetLife Stadium in New Jersey - more on that later - and at the 'Linc' in Philadelphia and at the more modest Audi Field in Washington DC.

The standard of play has been modest but South American clubs and their passionate fan bases have lit up the tournament, so much so that even the British and the Europeans have taken notice.

At least one Brazilian club will reach the quarter-finals after Palmeiras and Botafogo have met in the last 16 on 28 June in Philly.

Despite all its growing pains and controversial Saudi backing, FIFA wants this tournament to become a firm fixture in the international calendar, perhaps even on a biennial basis.

That's food for thought, but for now, as the tournament heads towards the business end, below are some takeaways from the group stages. Oh, but the most important observation first - I can assure you: Deutsche Bahn is no match for Amtrak.

Heat issues - and FIFA is partly to blame

Some of the weather problems have been self-inflicted by FIFA. And mitigation for extreme weather is within the world governing body’s power but they only intervene when the heat is as hot and dangerous as conditions that force migrant workers in the Middle East to stop for a break.

Just 15 out of 63 matches have kick-offs later than 6pm (or at 7pm, 8pm or 9pm in other words ) in a match schedule that is designed to accommodate European TV audiences - yet where most games are played late for European audiences anyway.

It's a repeat of the 1994 World Cup when lunchtime kick-offs were the standard and it doesn't bode well for next year's global finals when FIFA might squeeze in up to six matches in a day.

Just four matches at the 1994 competition kicked off at 7.30 pm. No less than 34 of the tournament's 52 were scheduled at noon in the gruelling heat of an American summer.

That led to a cacophony of complaints but not from Bora Milutinović, then the US national team manager. He yelled: "I hope it is 300 degrees and 2,000% humidity."

It's often felt like that on the East Coast; sultry, sticky and steamy. Yesterday, temperatures in New York City topped 100 degrees Fahrenheit, or 38°C.

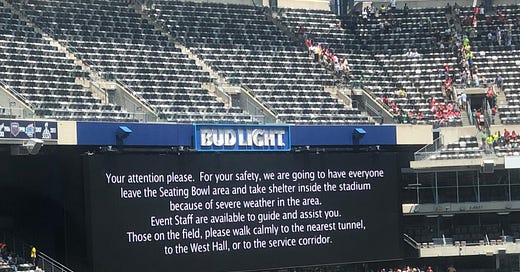

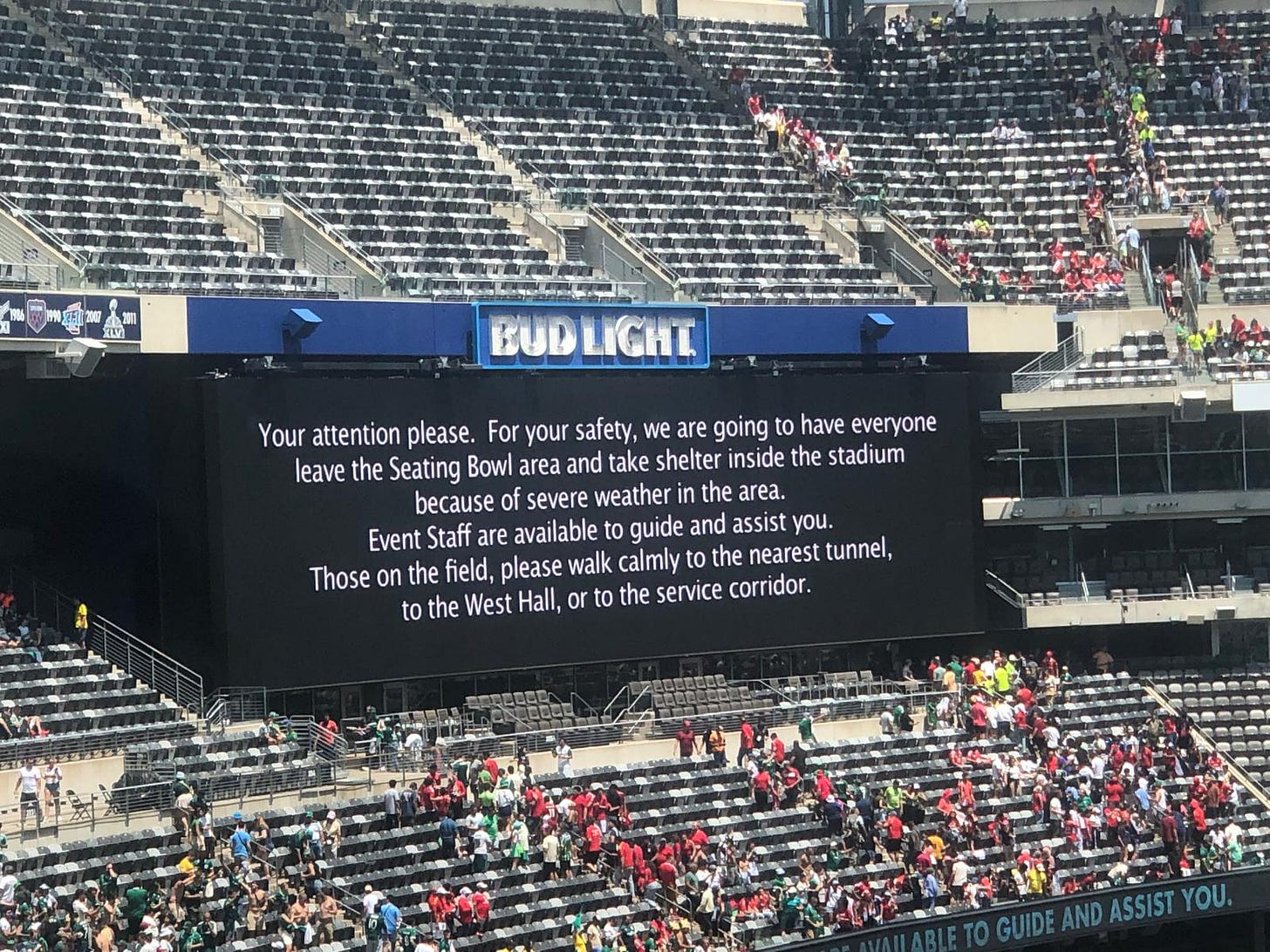

Weather events have led to scenes like the one below, detailed later in this piece.

A heatwave has also exacerbated concerns at the tournament. Borussia Dortmund's substitutes ditched the dugout for the dressing room to watch their match against Mamelodi Sundowns in a midday kick-off on 21 June.

Small countermeasures - ranging from ice towels to heated tents at Real Madrid's base to mimic match conditions - have been taken to tackle the heat, but the searing temperatures will have the back room staff of clubs worried.

FIFA's regulations are limited to cooling breaks implemented at the 30th and 75th minute of play when the wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT) exceeds 32°C / 89.6 F.

By comparison, the WBGT threshold for migrant workers in Qatar to abandon outdoor work is 32.1°C.

Without adjustments, the 2026 World Cup could become a repeat of the 1994 tournament when players buckled under the heat and the quality of play suffered.

The LA Times, like Milutinovic, took a different view and wrote about all those 'soccophiles': "If it's summer, it's hot and humid. Those in Alaska need not reply."

PIF vs Red Bull

Even ardent 'soccophiles' will have frowned at some of the fixtures at the Club World Cup.

Al Hilal versus Red Bull Salzburg on 22 June in DC, the American capital, was among the weirder match-ups and one that perfectly encapsulated the often questionable state of the modern game.

In the oppressive heat, the goalless draw was hardly unforgettable, but in blue, Al Hilal - once the club of Neymar - were an MCO serving the Public Investment Fund of Saudi Arabia and in white, Salzburg were an MCO serving energy drink behemoth Red Bull.

PIF owns Newcastle United and has majority stakes in three other Saudi topflight clubs. With a large Saudi expat community in the city, Al Hilal enjoyed the backing of their supporters in the stands dotted with green Saudi flags.

On the hoardings, PIF was advertising after becoming a late partner of the tournament, but who precisely were they targeting?

It was a reminder that Saudi Arabia's footprint is all over this tournament. In fact, through the $1 billion investment in SURJ, an arm of PIF, in streaming platform DAZN, Saudi Arabia are bankrolling this Club World Cup.

Outside the stadium's gate, there was however a poignant reminder of Saudi Arabia's dark side. A van with a billboard (below) depicted photos of Jamal Khashoggi and Turki Al Jasser.

In 2018, Khashoggi, a columnist for the Washington Post, was chopped to pieces with bone saws at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul in a murder that American intelligence later attributed to Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman.

Less known but no less brutal was the execution of Al Jasser on treason and terrorism charges on 14 June, the opening day of this Club World Cup. A prominent journalist, Al Jasser covered women's rights, the Arab spring and corruption in the Saudi royal family.

His crime? Running a Twitter account that highlighted these issues. The Saudi interior ministry said those crimes amounted to “high treason by communicating with and conspiring against the security of the Kingdom with individuals outside it”.

Latin flavour

The tournament has enjoyed an undeniable South American flavour. The Brazilian quartet of Palmeiras, Botafogo, Flamengo and Fluminense have been intent on the last sixteen since Day 1. Flamengo fans lit up Philly earlier in this tournament (below).

Boca Juniors and River Plate of Argentina both intended to make their nations proud. So what's prompted the 'renaissance' of a region that back in the '60s dominated the club game with Pele and Santos?

In 2023, the last final of the Club World Cup was a mismatch. Manchester City waltzed past Fluminense 4-0. The outcome had been somewhat predictable: the Rio club's revenue was $125 million, Abu Dhabi-owned City's was $900 million.

Besides, Fluminense had been at the end of their season, City were in peak condition ahead of the busy festive season.

That dynamic is reversed in the United States - the European clubs are at the end of their season giving South American and Brazilian clubs - in mid-season - the opportunity to go toe-to-toe with the moneyed elite, and perhaps even the edge.

Palmeiras manager Abel Ferreira has however dismissed the numbers game as an excuse. Major Brazilian clubs - competing in the domestic league, the Copa Libertadores and the cup - often play more than 70 matches in a season.

Until Monday, Brazilian clubs had remained unbeaten and provided some of the upsets of the tournament so far. Botafogo protected Igor Jesus's first-half strike to stun European Champions Paris Saint-Germain and Flamengo waltzed past ten-man Chelsea 3-1. Cole Palmer played out of position and Liam Delap failed to impress, but Flamengo were simply the better team. They attach importance to a competition that is frowned upon in Europe.

Former Flamengo president Luiz Veloso told Sporting Intelligence: "Brazilian clubs have been performing consistently in the group stages of the competition.

“It proves that Brazilian football has grown and is financially strong. It's important for the success of the competition as well - Brazil is an important market in the global game.

“PSG underestimated Botafogo who excelled tactically. Palmeiras has been the work of Abel Ferreira who is a very pragmatic manager. The knockout phase will be hard nonetheless for Brazilian clubs. Chelsea should have played better but Real Madrid and Manchester City are picking up."

At a news conference, Flamengo manager Filipe Luis, the ex-Chelsea full back, said: "There is an elite in football that is superior. Brazilian clubs are competitive at the second level of European football. Flamengo will no longer devalue themselves against any opponent, but the squads of the elite are better. That's a fact."

Luis is not wrong. The economic reality can't be ignored. In Deloitte's 2025 Money League, the recent Conference League winners Chelsea have a revenue of 545 million euros, dwarfing Flamengo's income of 198 million euros. The Rio club is the only South American to make Deloitte's top 30, albeit in last place. Red Bull Salzburg and FC Porto are the only two European participants in the Club World Cup that don't feature in the top 30.

So, it will still be a surprise if a European club doesn't prevail come the final on 13 July, but at least the Brazilians can dream of repeating Corinthians’ feat in 2012 when they were the last non-European club to win the Club World Cup, with a 1-0 victory against Chelsea in front of 30,000 of their fans among a crowd of 68,000 in Yokohama, Japan.

Meadowlands - a.k.a Dreaded-lands

Those fans might struggle to get to the final venue. The MetLife Stadium - which will stage next year's World Cup final - in East Rutherford is unloved.

The lustre and flair of the Big Apple - just across the Hudson river - feel far away in this corner of New Jersey. It would be akin to having England's national stadium in Reading. Tapping into the New York market is sensible for organisers and with a capacity of 82,000, the MetLife Stadium is the biggest NFL venue in the United States.

Admittedly, grumbling at major tournaments is always in fashion. But. The matchday experience at MetLife Stadium is simply dreadful. (Fans heading there pictured below).

The stadium has as much charm as its name. This reporter first attended a match at the venue in 2013 when he stumbled upon fans from Ivory Coast in Harlem who where on their way to a friendly against Mexico. The match was forgettable, the venue soulless, the crowd tiny and the trip home a nightmare. All these years later, not much has changed.

An Uber to MetLife Stadium can cost up to $150 for the short eight-mile trip from Manhattan. Public transport, including buses and train services, is limited and time-consuming. Parking costs $50. A beer will set you back $14.

The colossal three-tiered bowl has none of the charm or history of previous World Cup final venues, including Moscow's Luzhniki, Rio's Maracana and Johannesburg's Soccer City.

It hasn't helped that much of the football played at the venue has failed to set the pulses racing, often in front of meagre crowds.

Palmeiras's victory over Al Ahly was attended by just 35,179 fans. After 50 minutes they had to evacuate following a message with instructions on the big screen: "Your attention please. For your safety, we are going to have everyone leave the seating bowl area and take shelter inside the stadium because of severe weather in the area. Those on the field, please walk calmly to the nearest tunnel, to the West Hall, or the service corridor." (Photo higher up in this piece).

Adverse weather may present FIFA with problems during the World Cup. Imagine if the World Cup final got suspended.

FIFA's venue officer in Orlando joked with Gianni Infantino during the suspended Mamelodi Sundowns - Ulsan match: would he make the call?

A view from DC: FIFA hasn’t changed

Phaedra Almajid also spotted the van near Audi Field that was protesting at the Saudi killings of two journalists.

The whistle blower who exposed that Qatar bribed football officials to vote for the Gulf nation for the 2022 World Cup, lives in the United States and has kept half an eye on the Club World Cup, which represents deja vu for her - another major tournament backed by an autocratic Middle Eastern nation.

Over lunch this week in DC, Almajid was adamant in telling me: Saudi Arabia will be worse than Qatar in terms of human rights. Her view is that, at FIFA, an organisation that claims reform ad nauseam, nothing has changed.

Nice insight. Fifa is killing...

Excellent insights, Sam.