The Arab Spring, Libya and the African Cup of Nations: The effect of revolution and unrest has been to inspire, unite and embolden

. Matthew Barrett studied history at Oxford University, concentrating on the relationship between sport, politics and war in the twentieth century. He currently works in sports sponsorship and you can follow him on Twitter here. In his first piece for Sportingintelligence, he examines the impact of the Arab Spring on the performance of the Libyan national football team, considers how success can emerge from chaos, and how Libya now head into the African Cup of Nations 2012 with more optimism than ever. . .

By Matthew Barrett 16 January 2012 The 2012 African Cup of Nations begins on Saturday with a number of notable regional heavyweights conspicuous by their absence, including Cameroon, Nigeria and the champions of the past three tournaments, Egypt. Although the exploits of both Botswana and Niger in qualifying for the first time must be applauded, the most interesting names are those representing North Africa, not least Libya and Sudan as well as (less surprisingly) Tunisia and Morocco. At a tournament to be co-hosted by Gabon and Equatorial Guinea, the ACN 2012 kicks off with a match between Equatorial Guinea and Libya, in the Estadio de Bata, located in the port city of Bata on the Atlantic coast. The year of 2011 was an extraordinary year in North Africa, with the Arab Spring beginning in Tunisia and moving swiftly through the region. Alongside Algeria (who just missed out of qualification) and Egypt, all these nations have experienced significant upheavals and protests during the Arab Spring and in the case of Tunisia, Libya and Egypt, regime change. It seems implausible that national footballers could remain unaffected by such political turmoil and one could be forgiven for thinking the instability in these nations might have hindered the performances of their national football sides, especially given the tendency for them to be aggressively projected as a symbol of nationhood. On the contrary the results of North African national teams since the beginning of the Arab Spring, with the exception of Egypt, have been dramatically improved compared to the 12 months prior to the upheavals. Collectively these six nations have improved their win ratio from 33 per cent to 45 per cent and taken 1.64 points per match as opposed to 1.32 since the start of the Arab Spring in early 2011 when compared with 2010. Can this simply be coincidence? Or has the effect of revolution and unrest been to inspire, unite and embolden players representing their national teams, leading to such unprecedented success?

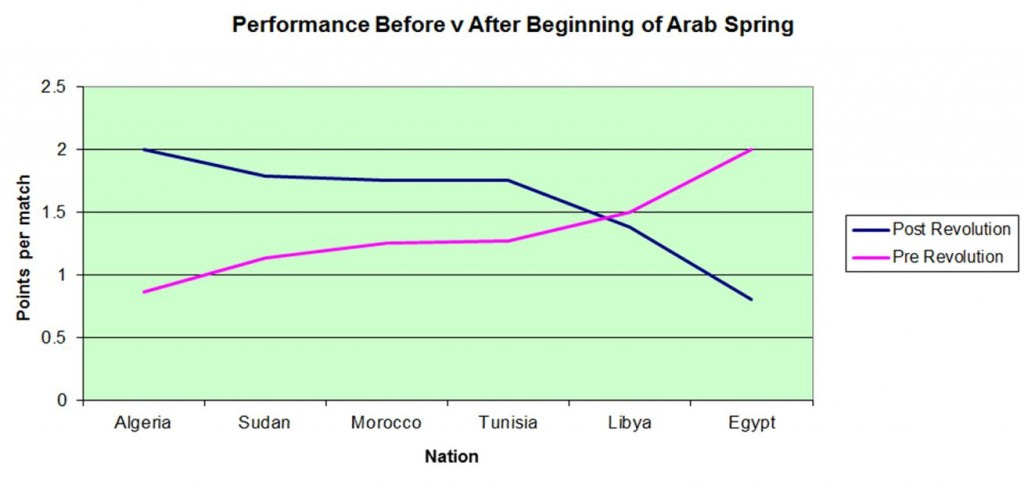

Of all the qualifiers, it is Libya that presents the most remarkable story. Despite the revolution against Col. Muammar Gaddafi plunging the country into turmoil and civil war for much of the year, Libya clinched the draw against Zambia they needed on 8 October 2011 to see them qualify for the tournament. Despite a recent poor run of friendly results, the Libyans are unbeaten in competitive matches since the revolution, notching up two wins and two draws to round off a qualification campaign that saw them go unbeaten and concede only one goal. By any measure, it was an astonishing achievement. It has certainly been done against all the odds. Libya have hardly ever registered in African football consciousness, with the sole exception of a runners-up spot in 1982 when they were the host nation (which can in part be attributed to a measure of ‘host country improved performance syndrome’ – see Germany 2006, South Korea 2002 and France 1998 for examples at World Cup level). Libya boast an abject record in both the World Cup (being the only North African country to never qualify) and the African Cup of Nations, with 2012 marking only their third appearance in the competition. Libya: football as a battlefield in the recent past The recent history of football in Libya was not just characterised by poor performances, but by the politicisation of the game principally through Gaddafi’s son Saadi, who was Hhead of the Libyan Football Federation, captain of the national team and had played for both of Libya’s dominant clubs Al Ittihad, who won six consecutive league titles prior to the revolution, and the club he once owned, Al-Ahly (Tripoli). Football became a battlefield in itself. The last 20 years of Libyan club football is littered with reports of stadium shootings, match fixing, bribery and even the razing to the ground of the Al-Ahly (Benghazi) stadium at the behest of Saadi. Whether it was to ensure the prominence of Al-Ahly (Tripoli) or prevent any defeat on the pitch from being viewed as a defeat of the regime, Saadi seems to have consistently attempted to manipulate Libyan football, and any criticism from the terraces was clamped down upon ruthlessly. Three fans were even sentenced to death and 31 fans and staff of Al-Ahly (Benghazi) arrested following club demonstrations and the dressing of a donkey in a Saadi Gaddafi replica shirt, while the National Transitional Council (NTC) recently agreed an investigation into the murder of former midfielder and coach Basheer Al-Rryani can begin. On a national level, while the players were showered with gifts from the regime, the influence of Saadi ensured that as a symbol of the regime, the results of the national team took on a political as well as sporting importance. The revolution Set against this backdrop, the Arab Spring and revolution against the Gaddafis (which unsurprisingly began in Benghazi) was highly likely to have an immediate, dramatic and destabilising effect on the nation’s footballers. With the Libyan league suspended midway through the campaign and the majority of the national side playing in the domestic league, the national squad was for the first time left in limbo. Even the minority of those plying their trade in overseas leagues experienced the same situation, with leagues suspended in neighbouring Egypt and Tunisia. The national squad and leading players and staff were not previously known for their politics; if anything they supported the end of corruption and nepotism of the Libyan Football Federation, but there was no sense of overt dissent within the ranks before the revolution. The then-captain Tariq Ibrahim al-Tayib, even told the BBC after beating Comoros 3-0 in March 2011 that ‘the whole team is for Muammar Gaddafi’, and later referred to dead rebels as dogs and rats, the decisive demonstration of Libyan football’s attitude to the conflict came in late June. In an open show of defiance to the captain's stance, 17 leading figures from Libyan football, including four members of the national side, turned up in the rebel-held town of Jadu in the Nafusa Mountains and declared themselves as opponents of the regime. One of them, Adel bin Issa, the coach of Tripoli’s Al-Ahly, announced he had come “to send a message that Libya should be unified and free”, and he hoped “to wake up one morning to find that Gaddafi is no longer there.” As coach of the club so inextricably linked to Saadi Gaddafi and the regime, it marked a watershed in Libyan football. Former national goalkeeper Juma Gtat defected alongside him, explaining to the BBC; “I am telling Col Gaddafi to leave us alone and allow us to create a free Libya. In fact I wish he would leave this life altogether.” From chaos to qualification Yet amidst such chaos and uncertainty, the Libyan national side has managed to qualify for the African Cup of Nations, and there is a case to suggest that this may have happened in conjunction with revolution rather than in spite of it. “This is for all Libyans, for our revolution” - so said 39-year old goalkeeper Samir Aboud in the aftermath of draw against Zambia, which put them though to the tournament as a best runner-up with an unbeaten record and a miserly defence. For Aboud, newly appointed captain of Libya and of leading club Al Ittihad, to make such a powerful statement that reverberated around the world was of supreme significance. For a team that was significantly affected by the ongoing civil war and political interference, qualification was a momentous achievement. Playing on neutral territory with a new flag, strip and anthem, coach Marcos Paquetá summed the mood up by stating the team was now "not only playing for football success but for a new government and a new country”. The team was fast emerging as a symbol of the new nation and despite playing abroad due to security concerns, saw vast swathes of the Libyan population turn out in the streets to support the side and celebrate qualification. With former captain and star playmaker al-Tayib notably absent, the new Libyan squad, made up from players from all parts of Libya and with only four players currently possessing more than 12 caps, in one act demonstrated its potential to become a powerful new unifying force post-revolution. Their performances thus far and qualification for the African Cup of Nations represent a good focus for new beginnings as the new nation moves into 2012. So how can this improvement be explained? Aboud and Paqueta both hinted that the players were inspired by the revolution and events at home. They mirror the comments of Nabil Maaloul, coach of leading Tunisian side Esperance who won the African Champions League in 2011, who asserted: “The events at home really stimulated our team and we believe that the players felt greatly liberated after what happened.” In contrast to a previous state of repression and manipulation, a new sense of liberalisation and increased freedoms has been epitomised by the success of the Libyan national side (and equally other North African football teams affected by revolution). Political protest and change seems to have sparked a new found unity, inspiration and rallying call on the football field, reflecting the mood and progress of the Arab Spring and symbolic of newly energised nations realising their potential. Through the power of experiencing seismic events at home and taking inspiration from their fellow countrymen, footballers have shown the ability to work together during the same period towards a common goal and success. Taking inspiration from political uprising and a sense of nationhood can only go so far; what is equally essential is this creation of a sense of unity amongst a group of players. Interestingly the two strands of thought mirror the same debate on morale of soldiers in war. First, the ‘legitimate demand’ premise rests on the view that soldiers will fight owing to an underlying commitment to the cause and certain values – in the case of Libyan football this would be translated as a sense of patriotism or pride in the emerging nation. On the other hand, the ‘primary group’ theory asserts that the “main influence on the soldier’s willingness to fight is the capacity of his immediate social group to supply his material and psychological needs, and engage his loyalties, irrespective of commitment to any larger cause’” (J.G. Fuller). This analogy could quite easily sit at the heart of any analysis on the recent exploits of the Libyan football team or those of the other North African sides who have performed so admirably in 2011. Whether it is a battlefield or a football pitch, it is always vital for individuals to know and share respect with those who they work closest with. In times of instability and hardship, it is these strong bonds that produce the best results. The Libyan football team were clearly not only playing for their national and people, but for each other. The 2011 highpoint in North African football was simultaneous to the Arab Spring upheavals. The two are clearly linked and it is not just Libya that serves as an example. Similar instabilities in Algeria, Sudan, Morocco and Tunisia have been followed by significant upturns in performance, as this graph shows:

Only Egypt provided an exception to the rule, with a chaotic qualification campaign closely resembling the uncertain situation in the country throughout 2011 that saw growing protests at the interim military government. Both the population and football side failed to rally in the same way as their North African neighbours. Perhaps Tunisian defender Khalil Chemmam summed it up best, stating: "One positive thing from the revolution was that, although we suffered a lot, those changes and the suffering made us stronger -mentally and physically." The 2012 African Cup of Nations provides Libya and the other North African nations a chance to show the rest of the world that they are striding purposefully forward in both politics and on the football field. .. Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter Sportingintelligence home page