'Sprinters don't improve after 30. Gatlin's feats are ... incredible'

By Roger Pielke Jr

20 July 2015

The fastest time in the 100m in 2015 so far belongs to Justin Gatlin, the American sprinter twice sanctioned for doping violations. That Gatlin has come back from suspension during 2006 to 2010 to become the top sprinter in the world today makes for a remarkable story. The fact that he is doing it at age 33, for some, makes the story a bit too good to be true.

At present, no one has outright accused Gatlin of achieving his current success by breaking the rules. But questions remain. Ross Tucker, an expert in athletic performance explained that "Gatlin is the problem that will not go away… he is a former doper, dominating a historically doped event, while running faster than his previously doped self."

For his part, Galin is aware of the talk, saying: "There's nothing I can do except go out there and keep running and pushing the envelope."

I was curious about how unusual Gatlin’s performance is as a 33-year old. Now that I’m closer to 60 than I am to 30, I have a soft spot for the older athletes taking it to the youngsters, like 33-year old Serena Williams, who at Wimbledon this month won her 21st tennis Grand Slam singles title and doesn’t seem to be slowing down.

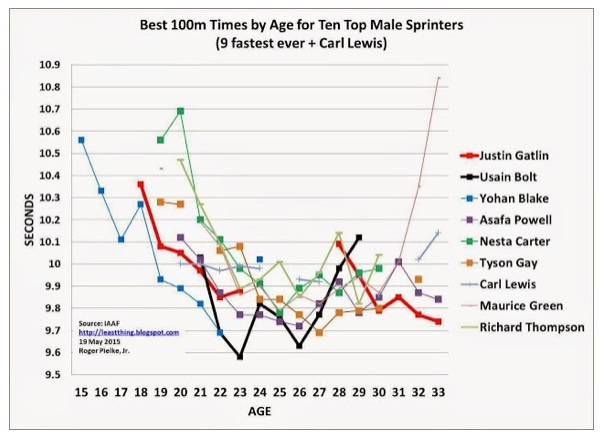

The first thing I did was to gather data from IAAF.org, which hosts a wonderful data repository, for the top nine sprinters ever at 100m, and compare how their times progressed as they aged. That data is shown in the chart below. (I added in Carl Lewis because I was curious.)

Article continues below

That chart is a bit noisy, but what it shows is how exceptional Gatlin’s improvement has been from age 28 to age 33, achieving successive personal bests. Gatlin explains that his doping suspension may be the cause of his late form: “I've been away from the sport for four years -- I literally didn't run for four years, so my body's been rested.”

He does have a point, since moving his times four years to the left would make his curve somewhat less unusual.

But the reality is Gatlin was not placed in a time capsule for four years. He aged like everyone else. If taking four years off from competition in the prime of a sprinter’s career is thought to lead to record-shattering times, then we’ll probably see more of it. But I am doubtful, given that the best sprint times occurred between ages of 22 and 27 for this set of athletes.

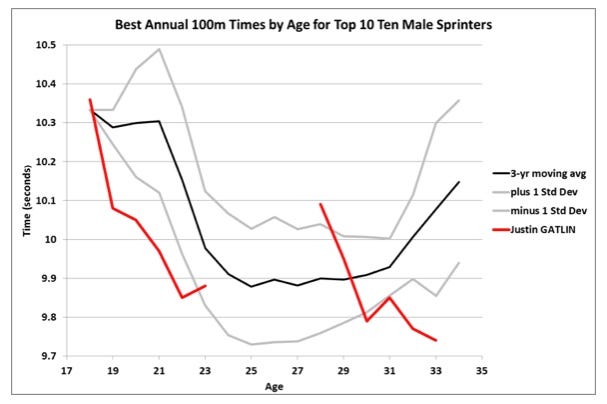

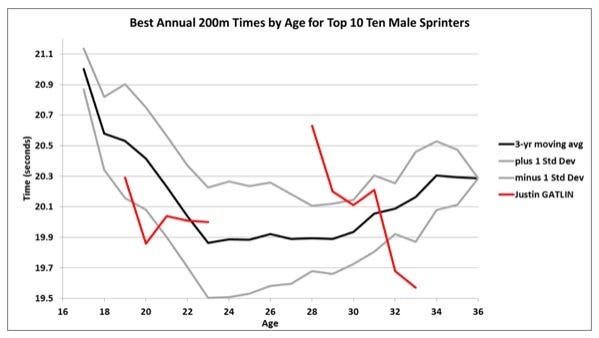

To better show the data I provided the following cleaned up version of the data, which shows a moving three-year average of times of the fastest nine athletes other than Gatlin, plus the one standard deviation bounds for the data. Once again, Gatlin’s times are shown in red. I also show the same analysis for 200m, where Gatlin has also been showing remarkable times.

Article continues below

The top 10 fastest male sprinters in the world stopped improving as a group by about age 25 for the 100m and 23 for the 200m. Gatlin’s times and improvement are, it is safe to say, unprecedented among these groups of runners.

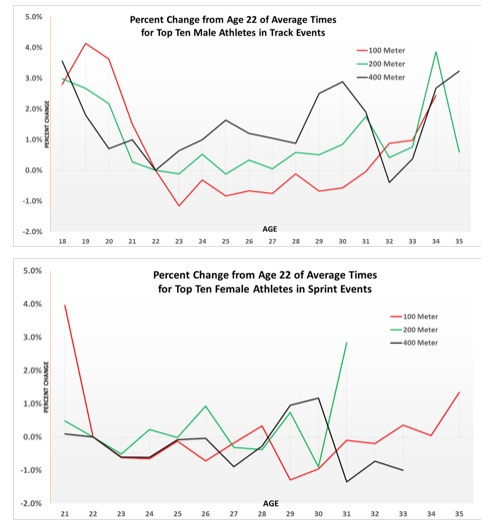

I have now expanded the analysis one step further. The following two graphs show the “age progression” of the 10 fastest sprinters, male and female, at 100m, 200m and 400m. Here the curves show the average times of these 10 sprinters for each age.

For both graphs I have set the average time at 22-years old to be 100, and the curves show improvement (faster times mean negative percentages) or degradation (slower times mean positive percentages) from that baseline.

Article continues below

These data show that the 10 fastest men in each event (including Gatlin in the curves this time) did not get much faster after their early twenties in the 100m or 200m. Interestingly, however, as a group, the men were at their fastest at age 32 in the 400m. From age 22 to 31 there is a noticeable difference in the evolution of times across the three races.

In contrast, the 10 fastest women in each race were at their fastest in their late 20 and early 30s, with their fastest times coming progressively later for the longer sprints (29 for 100m, 30 for 200m and 31 for 400m). Unlike the men, the overall progression of times for each race follows a very similar pattern. These data suggest all sorts of interesting questions that go well beyond where I started this analysis.

It is worth noting that these populations are not randomly selected, so extreme caution is warranted in trying to take these data to suggest something broader about male or female elite sprinters. What they do tell us is that in the 100m and 200m, the fastest runners ever, as a collective, do not improve after age 30. Once again Justin Gatlin looks to be achieving something remarkable.

Gatlin may or may not be serious when he says that "Hopefully I've got a good stretch of years right now in front of me and we'll see how that goes for me." Whether Gatlin ever again fails a doping test or not, the controversy is sure to remain, as some allege that his current performances reflect benefits of earlier doping. It is unlikely that science can ever prove or disprove those sort of claims.

If Gatlin continues to scorch the track into next year’s Rio Olympics, I am sure that we will be hearing a lot more about his incredible feats and the questions that they raise. One way or the other, the data show that Gatlin is currently doing something incredible. Whether those achievements are believable or not is another question altogether, and one that can’t be answered by looking at the numbers.

.

Roger Pielke Jr. is a professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado, where he also directs its Center for Science and technology Policy Research. He studies, teaches and writes about science, innovation, politics and sports. He has written for The New York Times, The Guardian, FiveThirtyEight, and The Wall Street Journal among many other places. He is thrilled to join Sportingintelligence as a regular contributor. Follow Roger on Twitter: @RogerPielkeJR and on his blog . More from Roger Pielke Jr Global Sports Salaries Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter