By Edmund Willison

25 April 2017

This week sees the return of the former darling of tennis, Maria Sharapova, after a 15-month drugs ban from professional sport. The highest earning woman in global sport plays as a wild card in the Porsche Grand Prix in Stuttgart from Wednesday.

In the wake of her positive test early last year for a recently banned substance, meldonium, her fans and other members of the 'tennis family', including some sponsors and media, sought a possible explanation to clear Sharapova’s name. One line was rarely heard - “The testers finally caught up”.

Herein lies the problem anti-doping authorities face: positives tests do not prove intent to enhance performance illegally. The discovery of a new drug that provides an unfair athletic advantage, followed by a spate of positives for that substance should increase faith in the job the authorities are doing. Yet a prevailing attitude among many is to entertain the myriad excuses put forth by athletes for their drug use: administrational errors, innocent mistakes, existing medical problems. The narrative becomes skewed.

The meldonium scandal is not unique. In the early Noughties there were similarly hundreds of positive tests for another substance, an anabolic steroid, nandrolone, across a range of sports from football to tennis, from athletics to martial arts to baseball. Arguably the two most famous positive tests (famous now, at least) belonged to a then football player, now manager, Pep Guardiola.

The respective journeys of Sharapova and Guardiola through the anti-doping prosecution process attest to the uphill battle anti-doping organisations can face. One admitted to the use of the drug, the other didn’t. One was cleared of intent, the other was cleared entirely.

Their stories illustrate how 'drug cases' in sport are often far from light and dark. A substance can be completely legal one day, totally illegal the next; legal in one situation, prohibited in another. Sportspeople need to be 100 per cent responsible for any substance in their system, yet are allowed to argue mitigation on why they might not be responsible.

Ultimately rules are framed in black and white. Innocent. Guilty. The uncomfortable reality is so many shades of grey.

The Sharapova and Guardiola cases underline different paths that athletes take to clear their names. Guardiola used a variety of defences over a number of appeals, while Sharapova was restricted to one line of defence after admitting to taking meldonium. The job of the authorities is ever more difficult – how do you separate the honest from the untruthful?

.

Pep Guardiola’s two failed tests for nandrolone

In late November 2001, the Italian National Olympic Committee (CONI) announced that Pep Guardiola, then playing for Brescia Football Club (left), had twice tested positive for nandrolone. The timing was devastating. After a period out of the game this was only his second official match for the club.

Guardiola had provided urine samples after a league game in Piacenza on 21 October and on 4 November 2001 after a match against Lazio in Rome; both samples showed levels of the anabolic steroid nandrolone above the permitted legal limit of 2ng/ml. The steroid can improve an athlete's ability to train harder, aid recovery by reducing fatigue and help the body build muscle by producing more protein. Its performance-enhancing properties are therefore applicable across almost all sports.

Nandrolone is detectable by testing for the presence of its metabolites 19-norandrosterone (NA) and 19-noretiocholanolone (NE). Guardiola’s urine sample from October showed the presence of 9ng/ml of 19-norandrosterone (NA) and 12ng/ml of 19-noretiocholanolone (NE), six times the legal limit, for the A sample. In the B sample 8ng/ml of NA were found; NE was not tested for. The A sample from the urine taken in November showed the presence of 5ng/ml of NA and 10ng/ml of NE. In the B sample, 6ng/ml of NA was found.

The disciplinary committee of the Lega Nazionale Professionisti (the Italian league) consequently fined Guardiola €50,000, suspended him from football for four months and required him to submit to random drug testing for the four months that followed the end of the suspension. La Commissione d'Appello Federale (CAF, or football's federal court of justice) upheld the decision after an unsuccessful appeal from Guardiola and his representatives.

Guardiola was adamant that he had done no wrong and the two positive tests had to be some sort of mistake. “A machine says I have taken nandrolone, but I know I didn't," he said. "Before Piacenza I only took the multivitamins that Dr. Ramon Segura, my trusted physiologist, has prepared for me for six or seven years. They consist of only specific vitamins, as evidenced by the more than 60 doping tests that I have undertaken over the many years of my career, all came back negative. I am innocent and I'm going to prove it.”

.

The role of Guardiola’s personal doctor

As Guardiola mentioned, his personal doctor at the time was Dr. Ramon Segura. Dr. Segura was also physician to another player who tested positive for nandrolone just seven months before Guardiola. FC Barcelona defender Frank de Boer failed a test for nandrolone after a UEFA cup match against Celta Vigo. He produced a result of 8.6ng/ml, again well over the limit of 2ng/ml.

In the initial disciplinary proceedings conducted by the CONI in December 2001, Dr. Segura argued that the supplements he had given Guardiola were contaminated and were the cause of the positive test.

The lead prosecutor Giacomo Aiello listened to more than three hours of testimony from Dr. Segura. Dr. Segura provided the list of supplements Guardiola’s defence had had analysed in a lab in Cologne in an attempt to argue that they had been contaminated with nandrolone. However Aiello stated that the results came back “negative” and specifically that no nandrolone metabolites were found in the substances. These supplements could not have been the source of the positive test.

It became clear that despite claiming contamination, Dr. Segura could not even be sure of the contents of these supplements. It was discovered during Guardiola’s unsuccessful appeal that Dr. Segura’s behaviour in preparing Guardiola’s supplements was deemed “risky”. These supplements were prepared with "raw materials purchased from different suppliers according to market availability", without suitable "certification of manufacturers".

This assumedly would have caused great concern to Pep Guardiola given his trust in the doctor whose supplements he had been taking for many years. Their relationship remained strong however. Dr. Segura returned to FC Barcelona in 2009, the same season Guardiola became club manager. Guardiola took a keen interest in the substances his former physician provided to his players. “Guardiola took this program of daily supplementation very seriously and insisted to the players on the need for it and made sure they followed it,” Dr. Segura explained.

(The anguish for the two did not stop after leaving the commune of Brescia. They would face another doping scandal soon after their reunion. In 2010 UEFA fined Barcelona €30,000 for failing to provide accurate details of their players’ whereabouts. When anti-doping officials arrived to take samples, the players were not present to be tested. Barcelona blamed a system failure for their inability to notify authorities of a change in their training schedule.)

Dr. Segura’s testimony as part of Guardiola’s defence in 2001 did not suffice. The appeal committee ruled that Guardiola’s punishment should be upheld and that:

The presence of the banned substance was incontestable.

The values of the nandrolone found were completely incompatible with the theory that the substance was produced naturally by the body.

The performance-enhancing effects of the substance were irrelevant to the case, it was the mere presence of nandrolone that was crucial.

.

Criminal proceedings and a new line of defence

The damage to Guardiola’s reputation continued – he faced criminal proceedings. Judge Matteo Mantovani of the Court of Brescia / Tribunale di Brescia dealt Guardiola a seven-month suspended prison sentence, a €9,000 fine and required him to pay the prosecution’s legal fees. This was the first criminal conviction for doping in Italy after the special law 376 came into force in 2000, legislating doping as a criminal offence.

Guardiola’s defence in criminal court differed to his civil case. Dr. Jordi Segura, not Dr. Ramon Segura, testified on Guardiola’s behalf. He attempted to demonstrate endocrinologically, yet unsuccessfully, that Guardiola suffered from Gilbert syndrome and this caused the endogenous production of nandrolone.

Gilbert syndrome is a genetic condition. People with Gilbert syndrome have mildly elevated levels of bilirubin which can sometimes give rise to jaundice (yellowing of the whites of the eyes and sometimes the skin). The condition is largely harmless and patients do not usually need treatment.

Brescia club doctor Dr. Ernesto Alicicco also protested Guardiola’s innocence. He testified that he had reviewed the substances Guardiola was taking, prescribed by Dr. Ramon Segura, and declared that there was not even a hint of suspicion that the substances were taken for doping purposes.

Dr. Alicicco himself was no stranger to doping scandals. In 1990, while AS Roma club doctor, two of his players tested positive for phentermine. Phentermine is a psychostimulant drug, pharmacologically similar to amphetamine, that is used medically as an appetite suppressant for short-term use and as an adjunct to exercise and reduced calorie intake.

Dr. Alicicco was forced to defend himself in consequent criminal proceedings. He was initially suspected by deputy prosecutor Silverio Piro of prescribing these “psychotropic substances [phentermine] for non-therapeutic uses." Alicicco was eventually cleared only for Andrea Carnevale, who was banned for a year for the failed test, to claim he was also given another substance, Micoren, by the Roma doctors.

“Some drugs like Micoren we took them, but I'm not a doctor and I do not know what to say the drugs were that they gave us,” he stated. The use of Micoren was widespread in Italian football in years gone by and has since caused great controversy.

Micoren is used as a support drug in the treatment of pulmonary disease and respiratory failure. It improves breathing, but, at least in the short-term, also has strong side effects: vasoconstriction, tachycardia, and cardiac and circulatory problems.

In 2005, an Italian judge investigated the suspicious deaths of three former Fiorentina players, who had taken Micoren, amid fears that drugs their clubs allegedly gave them triggered their fatal illnesses.

Dr. Alicicco would eventually respond to the claims of his former patient. “Carnivale remembers wrongly. Moreover he played for many teams, it is likely he was thinking of some other dressing room that he attended. And then, believe me, the Micoren was just fresh water,” Dr. Alicicco asserted.

.

Finally cleared

In 2007, there was finally some light at the end of the tunnel for Guardiola. After two failed appeals a shred of hope remained when Guardiola’s close friend, personal assistant and formal water polo great Manuel Estiarte (below left, still Guardiola's right-hand man at Manchester City) discovered changes in the World Anti-Doping Agency’s (WADA) guidelines which he thought could exonerate Guardiola.

In 2005, WADA had found that a phenomenon called “unstable urine” in samples could lead to positive tests for low levels of nandrolone. In very rare cases nandrolone could be found in samples not because of external administration but as a result of a chemical reaction that "may occur in a vial containing urine."

WADA instructed all accredited labs to perform “stability tests” on urine samples with nandrolone concentration from 2 to 10ng/ml moving forward. Guardiola’s values were at the high end of this scale (12ng/ml for NE). Those samples that were deemed “unstable” would not constitute an adverse analytic finding for nandrolone.

Then-WADA Director General David Howman stood by the efficacy of previous testing for nandrolone and said the chances of urine becoming unstable were “very rare”. The chances were between 1 out of 1,000 and 1 out of 10,000 positive tests for nandrolone.

Guardiola was cleared by the Brescia Court of Appeals. This was not because his samples were deemed “unstable” but because it could have been possible that his four samples had been “unstable”. Guardiola was absolved of all blame because of “the impossibility to now perform stability tests on the samples taken” in 2001.

Stability tests must be carried out within five weeks of the collection of a sample. In 2007, no sample even remained to be re-tested.

Yet Italian anti-doping prosecutors would appeal the decision in 2009 arguing that Guardiola should not have been allowed another appeal. The change in WADA’s guidelines did not constitute “new evidence”, they argued, because anti-doping laboratories were correctly following the testing procedures set by WADA at the time. Further they argued that Guardiola's representatives had never contested how the sample was collected or analysed in previous cases and that this did not form part of his previous defence.

This appeal was rejected and in 2009, beyond reasonable doubt, Guardiola was now an innocent man. His nightmare was over.

The same could not be said of his former teammate Frank de Boer. His defence, like Guardiola's first attempted defence, attributed his positive test to contaminated supplements. De Boer said he ingested the supplements while away on national team duty with the Netherlands. The supplements were Platina multi-vitamin pills from Ortho Company. Research showed that they did not contain any nandrolone and in fact the manufacturer took legal action against de Boer. As a result he was no longer allowed to name the company in the context of the doping affair.

De Boer, who was never cleared, was not the only high profile individual to be caught taking nandrolone in the early 2000s. So were footballers Edgar Davids, Jaap Stam, Fernando Couto, and Christophe Dugarry as well as seven professional tennis players. The Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) ruled the doping violations were caused by supplements given to the players by the ATP’s own physios. WADA rejected this explanation and called upon the ATP to investigate further. They never did, at least not publicly.

.

Why so many positives for meldonium?

In the three months after meldonium was added to WADA’s prohibited substance last year, there were 172 positive tests.

Maria Sharapova admitted to knowingly taking the substance during this time period and in so doing restricted herself to one line of defence – that she was unaware meldonium was banned. Some athletes escaped punishment after successfully arguing they took meldonium unknowingly. Others argued they had stopped taking the drug before its ban but it had yet to clear their system.

Instead Maria Sharapova explained that the reason for her doping violation was because she was unaware meldonium was a recently prohibited substance. Her agent claimed he did not go on his annual holiday since he was in the midst of a divorce. During this holiday he would usually take time to review WADA’s banned substance list for the upcoming year. Believe the excuse or not, Sharapova could have genuinely been unaware of the rule change.

The range of defences used by athletes to explain their failed tests underline how difficult it is for authorities to ascertain the truth. Yet these arguments all miss the point when it comes to the use of performance-enhancing drugs.

WADA eventually added meldonium to its Probihited List in 2016 due to “a growing body of evidence”, crucially including athletes’ statements, that the substance provided an unfair athletic advantage, was being used at alarming dosages and was being abused worldwide.

This extent of use was corroborated by WADA’s testing figures; in 2015 alone there were 3,625 meldonium positives. On the assumption that thousands of top-class sportspeople were not all suddenly stricken by conditions needing anti-ischemia medication, it appeared clear that, pre-2016, athletes taking meldonium were being provided with an unfair competitive advantage. (Or thought they were).

While the ingestion of the drug may have been “legal” before midnight on the last day of 2015, its purpose was to enhance performance. As with many forms of doping, they were all once “legal”. EPO, blood transfusions, anabolic steroids, meldonium – the drug testers generally do catch up, at some point. How much of a benefit meldonium provides will emerge with time.

.

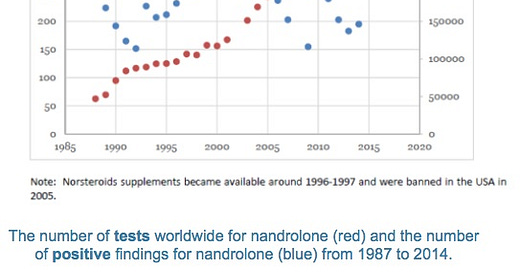

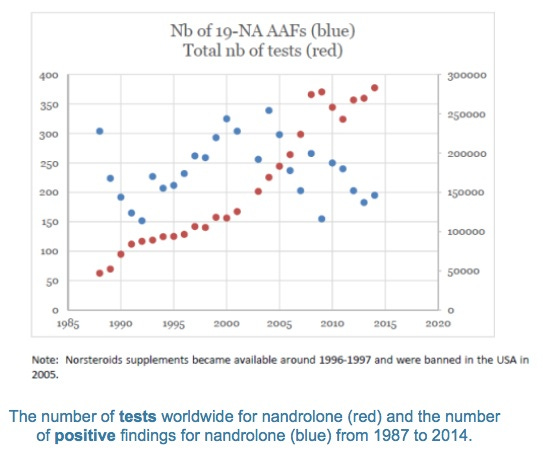

Why so many positives for nandrolone?

So what caused all the nandrolone positives? A phenomena as rare as “unstable” urine could surely not have accounted for so many failed tests.

In 1999, some 33 British athletes tested positive for nandrolone which was a 65 per cent increase on the previous year. Between 1999 and mid-2001 there were more than 600 positives worldwide.

Despite arguments, amongst others, that the spate of positive tests were because of the body’s natural production of nandrolone, the likely reason was predictably more sinister. Prohormones were banned by the International Olympic Committee in 1999, the year the wave of positives began.

Sportingintelligence spoke to Professor Christiane Ayotte, President of the World Association of Anti‐Doping Scientists, who believed this to be “undoubtedly” the cause.

“The reason for all these cases were undoubtedly, the presence on the market of dietary supplements containing what the industry referred to as “prohormones”, precursors of nandrolone such as norandrostenedione, norandrostenediol and isomers between 1995 - 2005,” she says.

Prohormones were introduced into the fitness supplement market by the US chemist Patrick Arnold in 1996. Arnold developed the designer steroid THG, also known as “the clear”, that lay at the centre of the BALCO drug scandal that uncovered the extent of track queen Marion Jones’ drug use, amongst others.

Prohormones are referred to by athletes and bodybuilders as substances that are expected to convert to active hormones in the body. The intent is to provide the benefits of taking anabolic steroids without the associated legal risks, and to achieve the hoped-for benefits or advantages without use of the steroids themselves.

With prohormones, Patrick Arnold used a legal loophole that allowed the marketing of anabolic steroids as long as they were previously unknown compounds (not listed on the banned substances list).

Arnold’s prohormone androstenedione was quickly followed by a number of other similar substances. They all had different effects, some being converted to testosterone in the body, but it was norandrostenedione and norandrostenediol that converted to the anabolic hormone nandrolone – the source of the positive tests?

These supplements were legally sold over the counter worldwide. While banned in professional sport, this was a contributing factor in their widespread use.

The sale of prohormones was banned as part of the Anabolic Steroid Control Act of 2004. From then on they were deemed anabolic steroids. The act states that “the term ‘anabolic steroid’ means any drug or hormonal substance, chemically and pharmacologically related to testosterone (other than estrogens, progestins, corticosteroids and dehydroepiandrosterone).” Apart from the definition, the document listed the presently known prohormones.

As prohormones could no longer be bought over the counter the number of positive nandrolone tests dwindled, almost immediately. Prohormones were manufactured solely for the fitness world – they never had a medical use.

.

The issue of responsibility

While this was surely the cause of the positive tests, the nandrolone epidemic was worsened by lax quality controls at the time surrounding dietary supplements. “Since the quality controls were absent, other products from the same manufacturers/distributors that were not labelled as such, were containing these steroids (prohormones),” Professor Ayotte says.

The issue of responsibility returns. Did some athletes unknowingly take supplements containing precursors to nandrolone? How many knew they did? Did Sharapova know meldonium was banned? Once again culpability is irrelevant when it comes to a level playing field. Prohormones, whether taken knowingly or not, provide an unfair athletic advantage.

And herein lies the difficulty the anti-doping authorities face. The results of drugs tests do not “strictly” speak for the motivations or intentions of an athlete. Drugs can be banned, the playing field can be levelled but when can intent be proven? So many nandrolone positives, so many meldonium positives, so many differing defences yet so few two-year bans – the punishment for a major drug offence.

At what point do excuses become irrelevant? EPO? Nandrolone? Meldonium? When is a legal drug so potent that athletes are still aware of its unfair performance-enhancing properties? One answer lies in the words of Brigitte Berendonk, an athlete on the East German doping program, when recalling a teammate of hers.

“He talked about the feeling of well being when he was on [a cycle of] his steroids. He would say he felt invincible and that he could tear out a tree with his all its roots; that was his strength. And whenever he walked into the arena he would feel this strong and this powerful. You feel you can beat any competitor when you are doped”.

Anabolic steroids: “legal” once upon a time.

.

Edmund Willison is a journalist and researcher specialising on doping in sport. He works closely with Hajo Seppelt from the German television station, ARD. You can follow him @honestsport_ew . FIXING, DOPING and whistle-blowing: secrets tennis wants to hide REVEALED: The best paid teams in global sport Follow SPORTINGINTELLIGENCE on Twitter