'Shankly's strength was his communion with the fans'

JOHN ROBERTS wrote for the Daily Express, The Guardian, the Daily Mail and The Independent, where he was the tennis correspondent for 20 years. He collaborated with Bill Shankly on the Liverpool manager’s autobiography, ghosted Kevin Keegan’s first book, and has written books on George Best, Manchester United’s Busby Babes (The Team That Wouldn’t Die) and Everton (The Official Centenary History).

As Matthew Engel once wrote in the British Journalism Review: "I suspect posh-paper sports writing changed forever the day John Roberts left the Daily Express to join The Guardian in the late 1970s, was handed a piece of routine agency copy and picked up a telephone to start asking questions.”

.

.

7 January 2010

.

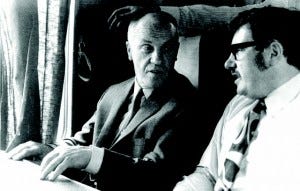

Rothmans Football Yearbook in hand, Bill Shankly paused in his stride towards the telephone at his home, turned to me and said: “I’m running every bloody club in the country.”

The aside was typical Shankly exaggeration. He was actually giving some clubs the benefit of his vast experience – some clubs, but not Liverpool, the one he loved to death.

It was early in 1976, about 18 months after his retirement as Liverpool's manager, and we were working on Shankly’s autobiography. The club Shankly had raised from second rate to sensational had made it clear to him that there would be no lingering association except as a spectator without a designated seat. There would be no directorship. There would not even be an invitation to travel to away matches with the team.

Considering Shankly’s overwhelming personality, Liverpool’s reluctance to embrace him after his resignation was as understandable as it was regrettable. He was not the type to sit quietly at the end of a boardroom table; even his presence at the team’s training ground was discouraged because players continued to greet him as “Boss” while they addressed his successor and former assistant, Bob Paisley, as “Bob”.

Behind his smiles, handshakes and witticisms, Shankly’s anger festered. He was deeply hurt and saddened, and said so in his book. Consequently it was unavailable at the club’s souvenir shop. “Some people think he’s an awkward bugger,” one member of the Liverpool staff told me. “But of course he’s an awkward bugger. If he wasn’t, we’d still be in the Second Division.”

Fast-forward to December 2009, and the 50th anniversary of Shankly’s arrival at Anfield. In marking one of the most significant dates in the club’s history, Liverpool’s followers were awash with nostalgia, yearning for the passion, deceptive simplicity, certainty, stability and glory that Shankly endowed to their club and which was perpetuated so stylishly by Paisley, Joe Fagan and Kenny Dalglish. They still yearn.

It has been said that Shankly’s ashes would be spinning in their urn over the current state of the club - owned by two Americans who appear to be as aligned as Obama and Bush - and at the state of a team labouring under the capricious Rafael Benitez to make a convincing impression in the Premier League.

Shankly would no doubt have views on what needs to be done while at the same time acknowledging the difficulties. Basking in Paisley’s deserved success, the Liverpool chairman of the time, John Smith, said: “When Bill Shankly was on the bridge, Bob was in the engine room.”

That begs the question: who is looking out for icebergs now?

One of 10 children, Shankly was raised in a poor mining village in Scotland and was familiar with hardship. For Bill and his four brothers, professional football provided a path to a better life and comparative wealth, though a maximum wage for footballers was in force throughout their playing careers. Indeed, Bill was in his third season as manager of Liverpool when the maximum wage (then £20 per week) was abolished. That alone speaks of a football world unrecognisable from the one today driven by television money, sponsorships, overseas owners, agents, imported players, greed and debt.

“I had problems trying to convince the directors that you couldn’t get a good player for £3,000,” Shankly said of his early days at Liverpool, before Eric Sawyer, of Littlewoods, became the club’s financial director and sanctioned the pivotal signings of Ian St John and Ron Yates.

The game has also changed in terms of physical fitness, speed and strategy, but remains relatively unchanged with regard to insistence on success, intolerance of failure and the gulf between a few wealthy clubs and the financially challenged majority. In spite of advances in communications, the distance between the players and the spectators has grown, chiefly because players with leading clubs are paid so much that is almost impossible for the average spectator to identify with them.

One of Shankly’s greatest strengths was his communion with the club’s supporters. They loved him for it. Pessimism was anathema to him, and he oozed self-belief.

He told me: “My career as a manager took me to Carlisle, Grimsby, Workington and Huddersfield, but during my time with those clubs I never felt that Matt Busby, at Manchester United, or Stan Cullis, at Wolves, were better managers than me. Not for one minute. I don’t mean to brag or boast, but I knew I had a system of playing and a system of training and I was clever enough to go on with it. I also knew how to deal with people.”

In the end, Liverpool did not know how to deal with Shankly, who died in 1981 after seven years in the wilderness. He would love to have walked through the Shankly Gates and would have smiled to see his statue, far bigger than himself. And infinitely smaller.

.

.

To purchase a copy of the recently re-published Shankly autobiography, 'Shankly: My Story' by Bill Shankly, with John Roberts, buy direct from the publisher with free UK delivery by clicking here.