REVEALED: contract rewards that put elite cyclists beside the world's best footballers

The best-paid footballers earn tens of millions. In solo sports, we know golfers and tennis players can make huge sums. But cyclists? They earn more than you think...

The average annual salary for a Premier League first-team footballer in England in the 2024-25 season was just over £4m. The highest-earning elite players were earning closer to £20m-per-year, basic, but an average of almost £80,000 per week across many hundreds of players across 20 diverse clubs is still huge.

It might therefore come as a surprise to many general sports fans that an annual salary of £4m+ per year, plus bonuses and prize money is not that uncommon in elite cycling.

Caveat: there are fewer elite cyclists than Premier League footballers and the £4m+ cohort in cycling is small, but there is big money to be had these days for the best on two wheels.

Tadej Pogačar (below), the 26-year-old Slovenian three-times winner of the Tour de France, in 2020, 2021 and 2024, is the highest paid professional cyclist in the history of his sport, having signed a €50m, six-year basic contract last year with UAE Team Emirates, which means he earns a basic €8.33m a year (£7m-a-year) for his on-bike activities alone, plus prize money and bonuses.

His contract, which runs to 2030, has a €200m buyout clause, and he will earn countless millions more on top of his UAE cash from endorsements.

I got thinking about this yesterday having read the latest post on Daniel Benson’s excellent Substack, which is dedicated to cycling. Daniel has managed to obtain a 30-page employment contract for a World Tour rider and posted in astonishing detail about how that contract breaks down.

Further down in this piece, I’ll re-publish the start of Daniel’s article - with his permission - and link you to the full thing. This kind of sporting financial minutiae has been the bread and butter of Sporting Intelligence since 2010.

I’m not a cycling aficionado. I’ve taken a passing interest in the Grand Tours since the 1990s, and, journalistically, have taken a more forensic interest in the systematic doping that has underpinned the sport since then.

Much of this work was recapped and extensively expanded in last summer’s “SKYFALL” series on this site, which looked especially at Team Sky’s drug-related issues since 2010.

Part 1 is here. 'Living a lie - exposing the dark underbelly of British cycling's golden age.”

Part 2 is here. “Injections at Windermere, drugs in the fridge, and lies about coming clean.”

Part 3 is here. “Drugs at the TdF, backstabbing, lies, cover-ups, omertà. Hello, British cycling.”

Part 4 is here. “British Cycling's nandrolone mystery before London 2012 Olympics.”

Part 5 is here. “Naming names, Jiffy-gate revelations and the Sutton tapes.”

Part 6 was a two-part podcast with Floyd Landis, and had this accompanying piece.

The finances of professional cycling have transformed over the past two decades, just as the finances of many sports have transformed, and often for the same reasons: capital injections from major entities, usually for PR reasons, whether corporate or sports-washing.

In cycling this might be Sky or the nation of the United Arab Emirates. In many other sports in recent times it’s been Saudi Arabia, most recently as MBS’s murderous regime has fostered an ever closer alliance with Gianni Infantino’s FIFA.

Related read: REVEALED: the full scale of Saudi Arabia's takeover of sport, costing tens of billions.

But back to cycling, where the historic cheating has been largely drug-based, and hasn’t involved the executions of minors without due process, or the imprisonment and torture of women who wanted to drive a car, or the murder and dismemberment of a journalist for disagreeing with MBS.

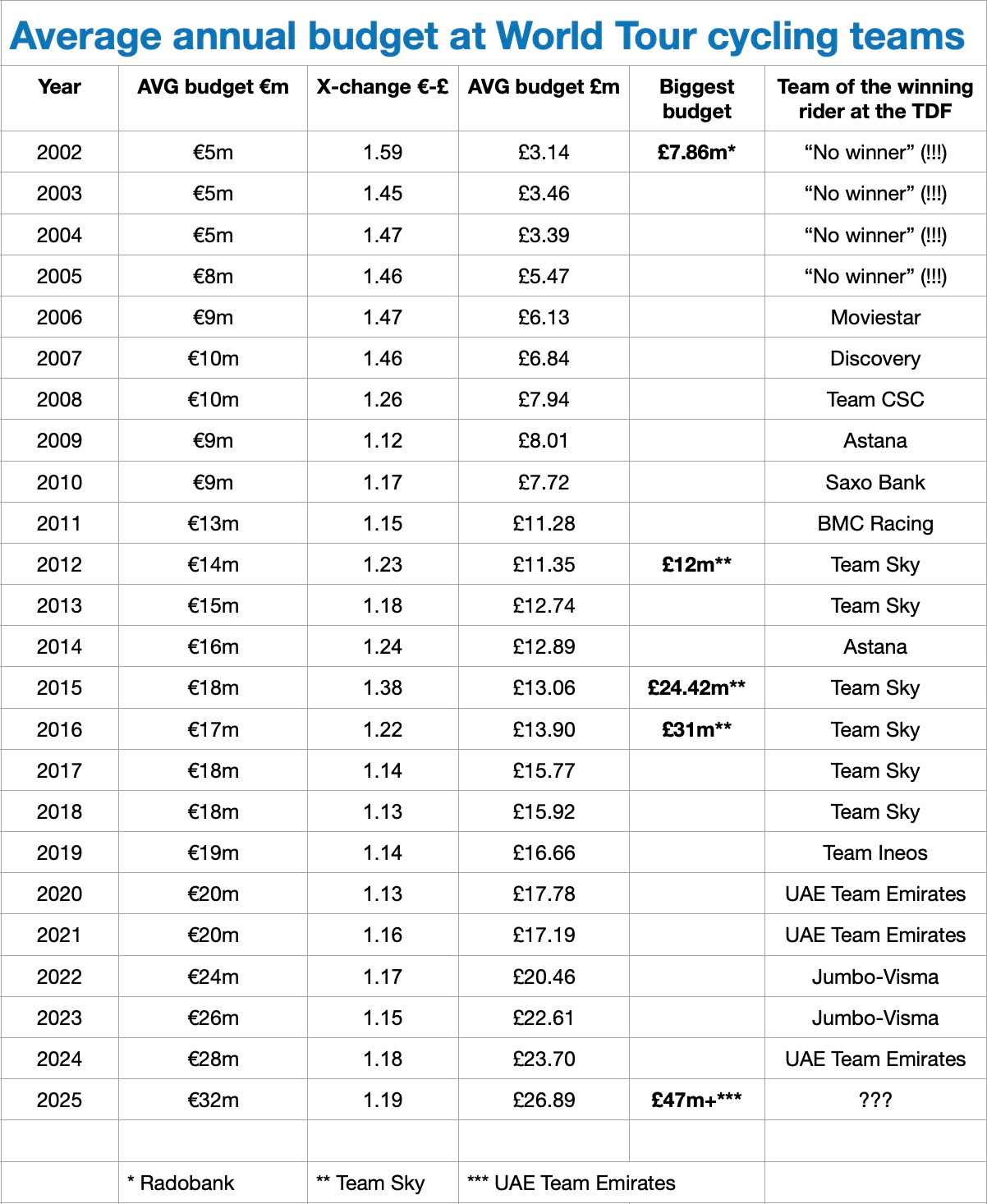

The economics of tour cycling have changed beyond recognition since the start of the millennium and the graphic below illustrates that.

These are official figures from the world governing body, the UCI, of average budgets of World Tour cycling teams (who take part in the major races such as the Tour de France and Giro), each year since 2002.

In 2002, the average team budget for all expenses was €5m, or £3.14m at contemporary exchange rates; and the team with the biggest budget, Rabobank, was double the average and then a bit more, at £7.86m.

By the time Team Sky had entered the fray and got established and won their first TdF in 2012, their budget, backed by Rupert Murdoch’s Sky TV, was the biggest in the peloton, at around £12m a year. Team Sky, and successor Team Ineos, would win seven of the eight TdFs from 2012 onwards.

The winning riders in those years were Sky’s Brad Wiggins (2012), Chris Froome (2013), then Froome three more times (2015, 2016, 2017), then Geraint Thomas (2018) and then Egan Bernal (2019 for Team Ineos).

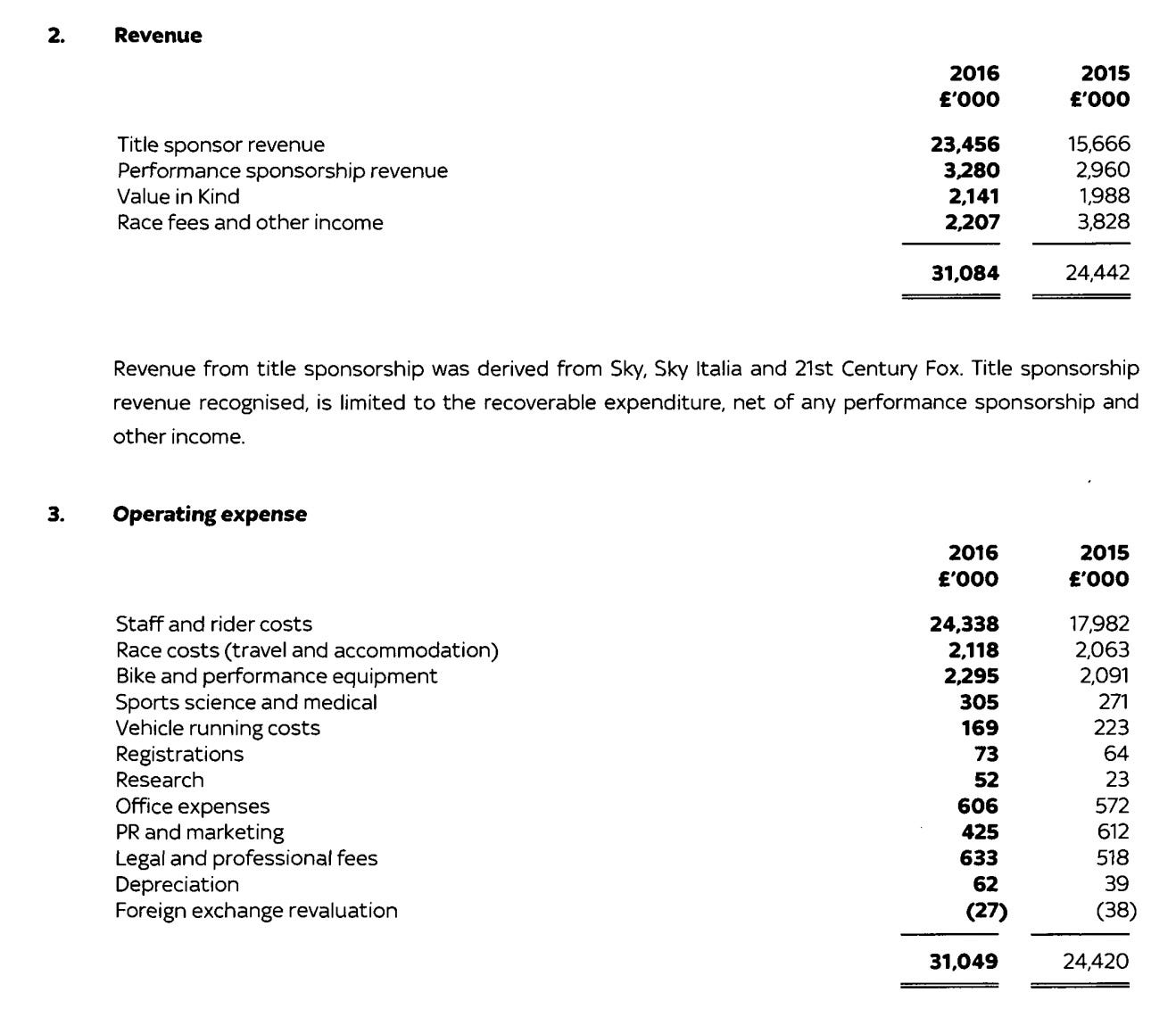

In accounts filed at Companies House for 2015 (below), we can see that Team Sky’s operating expenses were £24.42m that year and their staff pay (the vast majority on riders ) was £17.982m. These figures were pretty much double the sums being paid by the average team.

By the following year, Team Sky’s expenses had grown to £31m, and their staff costs (mainly to riders) to £24.338m. This was the year that Chris Froome won his third TdF and was earning a basic Team Sky salary of around £4m, before prize money and bonuses. His basic £4m-a-year was, very roughly, around 16% of Team Sky’s total employee salary budget.

I don’t have enough granular data for every year since then to be definitive but I suspect that the best rider in most elite teams (where there are an average of 20 riders), will be earning that sort of percentage of the total budget, or around 14-16% of all the basic salary pot.

It’s worth noting that Sky were paying £23.456m as Team Sky sponsors in 2016 (see graphic above), and by the time Sir Jim Ratcliffe was in his first full season as owner in 2020, of the renamed Team Ineos, sponsorship revenue (mainly from Ineos for team naming rights) was £46.374m.

Team Ineos haven’t won a TdF since 2019.

Sir Jim has a track record of spending a lot to achieve less than you’d expect from his investment. But that’s a Manchester United story for another day.

As for Daniel’s piece about a rider’s contract, the start of which is below, he reveals how this leading (unnamed) rider has:

an automatic €100,000 per year salary step increase.

a signing-on bonus worth a year’s money spread across the first two years.

various bonuses up to €1.5m for winning the TdF.

a raft of conditions about what a rider can and can’t do, from kit to behaviour to compliance with doping regulations to intellectual property exploitation.

Anyway, below is the start to Daniel’s piece, with links to connect to it in full, which contain an option to read it for nothing.

By Daniel Benson

(Read the full piece on Daniel’s Substack, over here).

We’ve all signed work contracts in the past. They’re typically full of legal terminology and clauses designed to protect the employer rather than the employee. But what exactly is included in a rider contract?

Of course, standard boilerplate contracts are provided by the UCI, but there are also specific contracts for riders and teams that cover topics such as violations, codes of conduct, bonuses, and responsibilities.

This story takes you inside a top-level rider’s contract and reveals the essential details typically found in the 30-plus-page document.

We won’t disclose the identity of the rider or their team. I could do without any headaches from irate teams, but we’ll refer to the rider as simply ‘the rider’ and cite the team as 'the team’. The name of the paying agent - effectively the company that owns the team’s WorldTour licence - has also been removed from the story.

However, we can note that we’re discussing a significant rider who had major bonus clauses that were in effect within the last 10 years. We’ll break down the contract into sections, just as it appears in the actual document.

The start of the contract is very similar to ones that we’ve all signed before, with wording that lays out the main parties, key terms, and length of services. In this case, services are: “The provision of services by you as a professional cyclist in the team and all other services associated with and related thereto, as reasonably directed by the team management.”

The contract in question is a two-year deal, with an option of a third-year extension. We’ll explain how the third-year option works a little later.

The first main section of the rider’s contract outlines the fee the rider would receive. While I won’t disclose the exact figures, the rider has a base salary for season one, followed by an increase of €100,000 for the second season. The rider is paid monthly, and in arrears, for their on-bike services.

There is also a signing bonus, which is indeed very common for riders these days. In this instance, the rider received a bonus of nearly the same amount as their first-year contract, spread across two instalments. The first half was paid directly after the contract was signed, and the second payment arrived immediately after the Tour de France.

The contracts then directly talk about bonuses. Here, the rider is presented with a selection of incentives.

(Read the full piece on Daniel’s Substack, over here).