Premier League debt falls £1.1bn ... not that you'll hear about it

By Nick Harris

28 February 2010

The combined debts of the Premier League’s clubs have fallen by £1.1bn in the past two years, although you wouldn’t know it from reading this in The Guardian, or this in The Independent, or this in The Times, or this in The Telegraph - Britain’s four major “quality” newspapers - or by reading this on the BBC website.

I have written for, or write for, all four of the papers mentioned (or affiliated titles), and I'm a fan of the BBC, whose website I use every day. But sometimes it’s baffling trying to comprehend the flagellation by the British press of Britain’s most successful sports competition ever. Because that’s what the Premier League is. That's why it's attracted so many investors. That in turn has led to its own problems, but let's use some perspective when detailing them.

Yes, Manchester United are owned by Americans who executed a leveraged buyout and saddled a previously debt-free club with £716.6m of loans. Large chunks of their massive profits now go to banks and other lenders in interest, instead of to the shareholders of a Stock Market-listed company in dividends or to fans indirectly in the shape of cheaper tickets.

And yes, Liverpool are owned by Americans who executed a leveraged buyout having promised not to, then failed to provide funding for a promised stadium while saddling the club with £237m of debts that they are struggling to afford.

When events like this happen at historic clubs with glorious pasts who have legions of passionate fans, many of whom are politically active in the widest sense, there will be protest, and there is nothing wrong with that.

Equally when a succession of people - a short-term glory-hunter, a not-so-rich dreamer, a shadowy stay-away and a naive businessman - succeed one another as the owners of Portsmouth, who last week became the first Premier League club in administration, then Pompey’s fans are justified in asking ‘How on earth can this happen?’

For the avoidance of doubt, the glory-hunter was Sacha Gaydamak, who bought into the club in 2006, leant it money to help build an FA Cup-winning team, and then got out, wanting his loans back. The dreamer was Sulaiman Al Fahim, who promised the earth and delivered sod all. The nobody was Ali Al Faraj, as elusive as Macavity. The businessman was Balram Chainrai, who shoveled in £17m of his cash as Portsmouth crumbled in the mistaken belief he’d be a preferential creditor, post-administration, if things went wrong. (One common link between all these men is the “super agent”, Pini Zahavi, but that’s a whole other story.)

Elsewhere in the Premier League you’ll find some chairmen and owners who spend too much money and have to underwrite debt themselves, as chairmen have in English football ever since clubs began. It’s on a bigger scale now because the Premier League is the most successful competition in English sport, ever.

But why the need to exaggerate problems and willfully fail to give your readers and / or viewers a balanced picture? (Apart from the bleeding obvious reason, of bad news making better headlines; surely we can do better than that?).

Back to those debt figures. Uefa, football’s governing body, has just produced a report, The European Club Football Landscape, that examines the financial workings of more than 600 top-division clubs from across Europe. For the Premier League clubs it used data - from official financial records - from the 2007-08 season.

The Guardian’s brilliant football business writer and investigator, David Conn, used that same data when he compiled a report for his newspaper, published nine months ago, in June 2009, that assessed debt in the Premier League. The headline on Conn's accompanying news story back then told the tale: 'Latest figures show Premier League clubs owe £3.1bn'. A paragraph near the top of the story said: "Manchester United and Chelsea were by far the most indebted, owning £699m and £701m respectively, Arsenal were third, with £416m debts and Liverpool, the other top four club, were understood to owe around £280m; their accounts, due to be filed at Companies House last week, are overdue."

For his typically detailed, forensic report, Conn used the 2007-08 figures for the 20 clubs who were in the Premier League in 2008-09, including promoted Hull, Stoke and West Brom's numbers from their Championship seasons, but not giving figures for Reading, Birmingham and Derby, who had been in the Premier League in 2007-08 but had gone down. If he'd used the 20 clubs who formed the 2007-08 season, his £3.1bn debt figure would have been about £70m higher, but that's a trifle.

Fast forward to February 2010 and the release of Uefa's report, using the same 2007-08 Premier League data for 18 clubs in that division that year (West Ham and Portsmouth not counted, for reasons explained later), and - surprise, surprise - it's more or less what Conn told us last June, give or take the difference made by the different clubs, plus some different application of exchange rates.

Uefa is saying that the clubs who were in the Premier League two seasons ago had about 3.8bn euros of debt. Using an exchange rate from summer 2008 of 1.26 euros to £1, and factoring in the slightly different make-up of clubs, Conn's detailed story of last June has now been "revealed" as "news" again, nine months on. So far, so good.

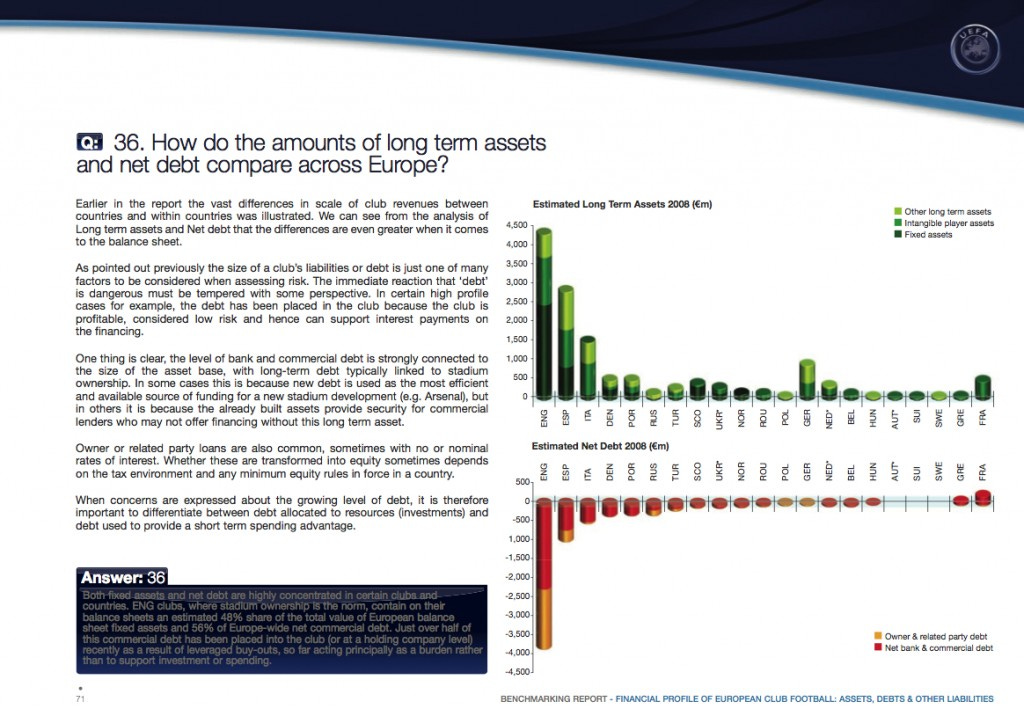

But hold on, there's more. Uefa also tells us (if you work it out from the graphs below) that those English clubs owed about 2.3bn euros (£1.8bn at 1.26 to £1) in commercial loans to banks and financial institutions and about 1.5bn euros (£1.2bn) to owners and related parties. Again, differential exchange rates muddies things just slightly.

Uefa also points out that just 17 per cent of clubs in top divisions across Europe own their own stadiums, with ownership prevalent in England, Spain, Northern Ireland, Norway and Scotland, and nowhere else. Municipal or state ownership is most common elsewhere. This ownership of property explains why English Premier League clubs alone (one division among dozens) own 48 per cent of the entire value of European football's assets, by balance sheet.

To quote that section in full: "Both fixed assets and net debt are highly concentrated in certain clubs and countries. English clubs, where stadium ownership is the norm, contain on their balance sheets an estimated 48 per cent share of the total value of European balance sheet fixed assets and 56 per cent of the Europe-wide net commercial debt. Just over half of this commercial debt has been placed into the club (or at a holding company level) recently as a result of leveraged buy-outs, so far acting principally as a burden rather than to support investment or spending.”

That 56 per cent became the story last week, as in the Guardian's splash, carrying the headline: "Premier League clubs owe 56% of Europe's debt". The sub-heading gives immediacy and momentum when it says "English clubs' debt mountain reaches £3.5bn". Given that the same paper told us about £3.1bn last year, and uses "reaches" in the present tense this time, things are surely getting worse, to the tune of £400m in a year? Blimey, Portsmouth on the edge and debt is continuing to soar. That was the tone as the story was repeated elsewhere, ie, plagiarised and repeated without the engaging of critical faculties.

Yet Premier League debt dropped £1.1bn in that time. Yes, dropped £1.1bn between Conn's original £3.1bn piece and Uefa revealing 3.8bn euros as news nine months later.

Arsenal's debt has fallen from £416m to £212m. Roman Abramovich has cleared that £701m owed by Chelsea. Yes, Manchester United's debt has gone up again, to £716.6m, but even Liverpool's debt is down £43m from the reported £280m to £237m.

Was there one single sentence in any of the stories that talked of 56 per cent of Europe's debt that even hinted that the debt had dropped by £1.1bn since then?

Not a word.

Actually, the debt has dropped by even more than £1.1bn; Uefa's figures didn't include debts from West Ham and Portsmouth because their books weren't in good enough shape to get a Uefa licence. So the total debt would actually have been more than 3.8bn euros then, and the total debt now including West Ham and Portsmouth's is less than £2bn, and three clubs (Man Utd, Liverpool and Arsenal with their 'good' debt) share £1.2bn of that, with the other 17 clubs sharing the balance between them.

Was there anything in all these reports about debt this past week that told you recalculating the figures would probably show English clubs now hold 47 per cent of commercial debt (at most), not 56 per cent, and quite possibly a smaller sum than that? No. If only somebody could discover the true debt figures for Real Madrid and some of the other giants, some truly interesting sums could be done. Prof Jose Maria Gay de Liebana, football finance specialist at the University of Barcelona, reckons Real's real debt is £609m, not £296m as claimed, while he says Barcelona owe more than £400m, and each of the Milan clubs about £350m now. You can't see that from Uefa's report, which raises other questions about it.

To point out that these things have not been explored in more detail in the British press this past week is not a criticism of individuals but highlighting a culture that a) sees just a negative side; b) fails to ask 'What's really happening here?'

As recently as this morning in The Observer, two of the finest, smartest sports writers working in Britain repeated the £3.5bn claim in the present tense and the 56 per cent line respectively without qualification in their pieces.

Of course Arsenal do get some praise for their positive business model, rightly, despite still holding the third-largest debt in the Premier League. And Randy Lerner at Aston Villa, whose team played valiantly in defeat in the League Cup final this afternoon, is lauded, rightly, as a benevolent owner to date. The 'two Davids', Gold and Sullivan, perhaps don't get enough credit for their reshaping of Birmingham over 16 years. Tottenham are turning profits regularly, and Dave Whelan is going all debt-to-equity-ish at Wigan, and chairman John Williams at Blackburn is saying things look brighter there than a year ago, and did you hear that Stoke have just posted a profit and are heading into the land of the debt-free? Probably not. But all of those things are true.

And unless you saw the Mail on Sunday's story on debt this morning, you might not have heard that Uefa, despite the wiping of debt at Chelsea and Manchester City by billionaire owners, still want to ban those clubs from European competition under their proposed Financial Fair Play rules, and let Manchester United play on. Uefa's general secretary Gianni Infantino is quoted as saying: "United is, of course, very well managed by David Gill and as long as they can still make a profit at the end of the year, it's fine. In the long term, though, the question is whether they can still afford this debt."

It's a funny old game. TV rights remained on the up domestically when last sold. International rights are about to double. Parachute payments about to leap to £16m per year for two years for those who drop out of the Premier League.

Meanwhile, according to Uefa's report, which seeks to highlight the need for Financial Fair Play, the most unbalanced leagues in terms of income (between the richest four clubs and the rest) include Latvia, Ukraine, Lithuania and Scotland, just ahead of Spain. In Spain the imbalance is a factor of six between the average income of the biggest four clubs and the average of the rest. In all the other nations mentioned it's higher. In Italy it's a factor of 4.2. In England it's 3.2, which is just higher than Germany and France.

According to Uefa's report top-flight clubs in Ukraine spent 116 per cent of income on wages (ie: almost a fifth more than all the money they earn). In Georgia it's 112 per cent. In Israel 102 per cent. In Russia 78 per cent. In France 71 per cent. In England: 60 per cent, which is lower than in Spain and in Sweden, and just above the Netherlands.

More on that later. Not.

.

See what's making the headlines on sportingintelligence's front page

Read more columns by Nick Harris

NB: Graphic below from Uefa's report (mind the two-year gap now!)

.