Paquetá rides a spot-fix rollercoaster as football corruption abounds

West Ham's Brazilian star has been charged with deliberately getting booked, four times. He says he is innocent. His case is the latest in a long line of betting scandals in the game.

West Ham’s 26-year-old Brazilian attacking midfielder, Lucas Paquetá, spent Monday at the Universal Islands of Adventure, an amusement park in Orlando, Florida. He was there with his Brazilian international team-mates including Bruno Guimarães of Newcastle, Douglas Luiz of Aston Villa, Andreas Pereira of Fulham and João Gomes of Wolves.

They’re in America for two Brazil friendly matches, against Mexico on Saturday in Texas, then against the USA next Wednesday in Florida. This is all a precursor to Brazil playing in the 2024 Copa América, which runs from 20 June to 14 July across the United States.

Paquetá looked like he didn’t have a care in the world as he posted photos from the theme park during the players’ day off. And yet he’s facing six FA spot-fixing and non-cooperation charges that, if proven, might see him banned from football for life.

The player himself vehemently denies any wrongdoing and when charged last month said he was "extremely surprised and upset”, and vowed to clear his name. “I deny the charges in their entirety and will fight with every breath to clear my name,” he said.

He was originally meant to file a formal response to the charges on Monday, but his lawyers were granted more time by the FA to consider his plea, so he was free to enjoy the Jurassic World VelociCoaster instead.

The Brazilian football association, the CBF, initially imposed an effective suspension on Paquetá last August when it became public he was being investigated. He was dropped from the squad to play games the following month. But last week the CBF cleared him to play in the Copa America having checked with the English FA that he isn’t currently suspended.

We’ll return in a short while to the specific accusations against Paquetá - that he deliberately got himself booked four times in West Ham games between November 2022 and August 2023, and a number of people on the island where he grew up profited from betting on those incidents.

Sporting Intelligence will make zero assumptions about Paquetá’s guilt or innocence. We have limited access to detail about the motivation of his acquaintances who gambled, and no knowledge of what evidence underpins the FA’s decision to charge him.

But spot-fixing and match-fixing in football are common, all over the world, including in England, and have been for decades. This is increasingly so in the era of online gambling and gargantuan unregulated markets in many regions, not least Asia. It is difficult to prosecute, but technology is changing that.

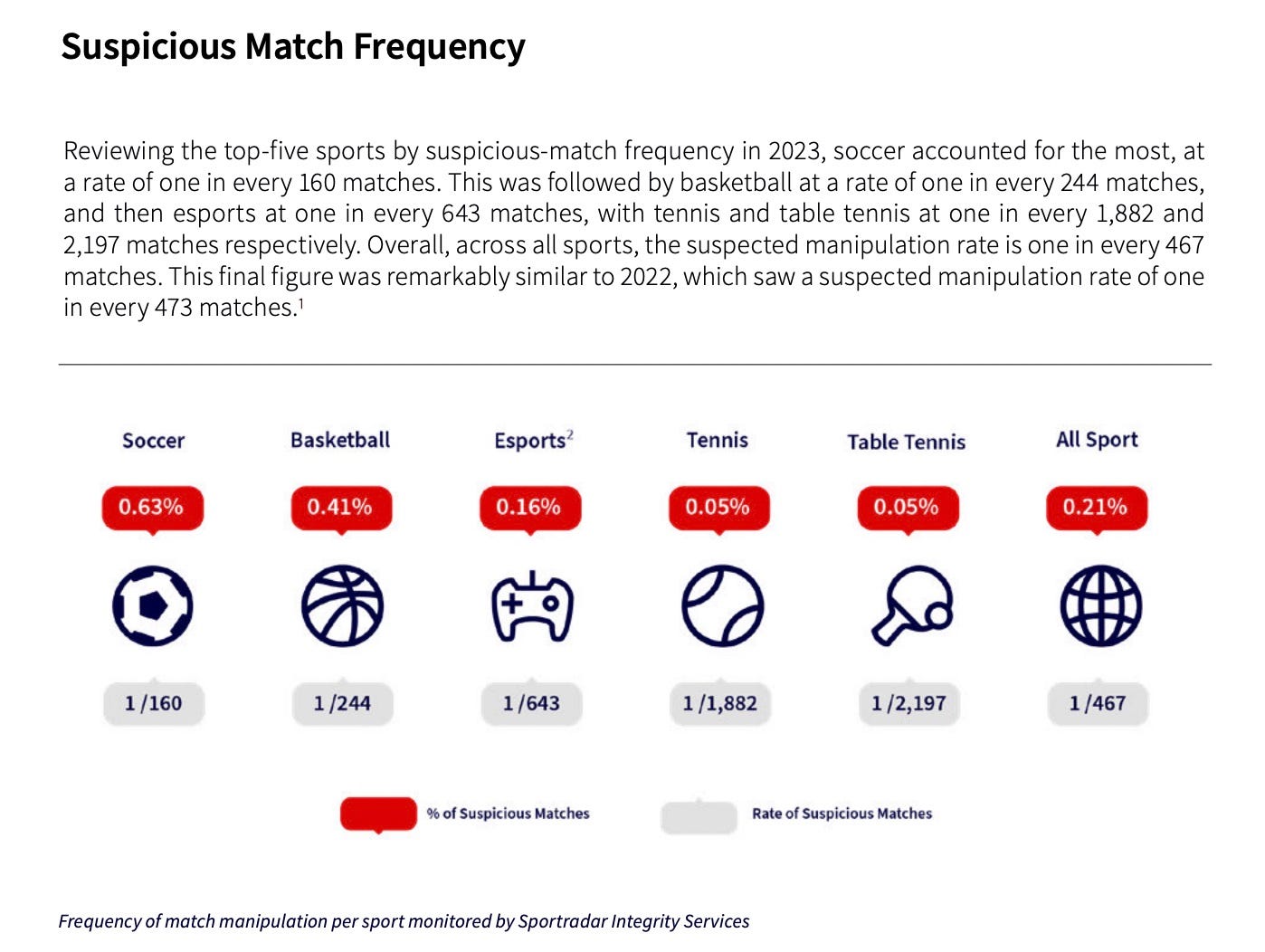

Multiple times a year, one of the self-proclaimed integrity wings of various data and betting companies will publish a report that attempts to quantify the current scale of betting corruption and match fixing. Sportradar published their most recent report in March (link to PDF here), saying they had identified 880 suspicious football matches globally in 2023, or 0.63% of all matches they monitored.

“The number of countries that witnessed at least one suspicious match rose to 85 in 2023, compared to 70 countries in 2022,” that report said. “The most significant rise in match numbers year-on-year was seen in Europe, with a 15% increase in suspicious matches, with smaller rises noted in Asia, South America and other regions taken as a whole. Meanwhile, of the 85 countries affected globally, 36 were in Europe, 18 in Asia, eight in South America, and 23 from Africa and North America combined.”

Suspicious matches include fixed outcomes of whole matches and spot-fixed events within matches.

Another recent integrity report, specifically about football in 2023, was published earlier in 2024 by StarLizard Integrity (PDF linked here), and said they had detected “only” 167 suspicious matches, or 0.26% of 65,000 matches analysed.

I’ve met lots of people over the years who have fixed football matches, whether at conferences where they have been whistle-blowing guests, or on their doorsteps when I’ve gone to ask them about their activities for some or other investigation.

I’ve met football folk who have been victims of match-fixing, either managing or playing against a fixing team. In Sydney last summer at a writers’ festival, I met Steve Darby, a veteran coach from Liverpool who has worked extensively across Asia, including in Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore, Thailand, India and Laos.

After I’d spoken as a member of a panel about betting-related corruption, Steve introduced himself and told me fascinating stories about the scale of fixing in some of the places he’d worked. On the last day of the festival he handed me an A4 sheet of paper with a list of games he knew first-hand had been manipulated, including some international matches.

When I tweeted last month about the potential trouble that Paquetá could be in, Steve replied: “It goes on all around the world and as often the offender is on the winning side it goes undetected.”

One match-fixing case in England that was detected, and that I covered closely at the time, happened in a League Two game between Accrington and Bury in May 2008. Bury won 2-0 and almost a year later, the FA charged four Accrington players and one Bury player (a former Accrington player) with betting infringements.

An official inquiry concluded: “There are serious concerns that the match was fixed.”

No match-fixing charges were ever brought because, according to senior FA sources, proving beyond doubt that a match was fixed had been deemed virtually impossible, unless someone involved in a fixing plot became a whistleblower. I spoke to one of the players involved and of course he said he was entirely innocent.

The players were only caught in the first place because they were filmed pre-match on CCTV at a branch of Ladbrokes in Liverpool, placing cash bets of between £1,000 and £5,000 on Accrington to lose.

Four of the players ended up with bans of between five and eight months, and fines of between £2,000 and £5,000. The conspiracy to fix that match was so widely known, locally, before kick-off, that hundreds of other people bet on Bury.

The following April, betting was suspended on a low-profile non-league match between Grays Athletic and Forest Green Rovers in the Blue Square Premier because of suspicious bets.

It was estimated that around £50,000 was gambled in sums up to three figures on Grays being behind at half-time but winning. This odd combination, priced at 22-1, would typically have attracted minimal sums across the industry as a whole, in bets of no more than a few pounds each.

The pan-industry gamble meant most markets were stopped a day before the game and rumours were rife before kick-off about a fix. Grays subsequently fell 1-0 behind at half-time but went on to win 2-1, in line with the “unusual” money.

The incident was reported to the FA and the Gambling Commission and an investigation began. A spokesman for Blue Square – sponsors of the league – told a BBC Radio 5 documentary that he believed the game was fixed. No further action was taken because the Gambling Commission - an utterly useless organisation in tacking betting-related corruption, in my personal opinion - said it lacked evidence to prosecute.

From the early 2010s, for several years, there were rumours, backed by sporadic bursts of highly unusual betting activity, that some clubs in England’s Conference South had players who were fixing games. Then in late 2013, in Australia, 10 people, including English players who had previously played in the Conference South, were arrested in a huge match-fixing scandal. Four English players pled guilty to match fixing in Australia and were given small fines but lifetime bans. I wrote about that episode here. That scam was orchestrated by a long-standing Singapore-based fixing syndicate.

Parts of that story were unintentionally hilarious. Emboldened by new laws, the Australian police had wire-tapped suspects’ phones, and bugged a whole club, including the pitch and even the goalposts. They collected evidence including calls arranging fixes, discussions about cash transfers and yells between team-mates during play along the lines: “Let this one in!”

What wasn’t so widely reported at the time is that a group of other suspected English match-fixers had fled Australia back to England, and in some cases back to the Conference South, before the arrests were made Down Under. It seemed likely there were a group of match-fixers, never arrested and hence untainted, back in England playing football.

I asked the English FA what they were doing to monitor these players and the FA wouldn’t say, so the assumption was nothing. I went to the home of one of those players in east London but he didn’t want to talk.

Probably the most dramatic case of fixing I’ve covered in England was a spot-fixing case where a player got himself sent off. He was a gambling addict with money problems and in debt to an unregulated bookmaker, who I was told could turn certain knowledge of a red card into a payday, probably in the Asian markets.

The story made the front page of The Independent in April 2008.

After deliberately getting sent off, the player - who had multiple addictions and was prone to depression - subsequently sought professional help for his addiction, and was said to be "ashamed and full of remorse" about what happened.

I uncovered the story while spending a few days researching a story in early Spring 2008 at the Sporting Chance clinic in Hampshire, co-founded by the former Arsenal and England captain Tony Adams.

Sporting Chance is Britain's foremost treatment centre for sports people with addictive illnesses, and I had got to know its late chief executive, Peter Kay. Like many journalists, I’d covered Adams’ story of addiction and recovery, and had written extensively on footballers and addiction. There had been an explosion in gambling addiction by 2008, largely due to the increasingly easy access to online betting.

Kay invited me to visit the house where various players were having residential treatment for a range of addictions. He allowed me to sit in on a group therapy session - with the permission of the players, including one who had played for England a few years before - and under the condition that no player would ever be identifiable from anything I subsequently wrote.

I heard the story about the red-carded player, and Kay said I could write it, confirming it on the record, as long as the player was not identifiable. The FA later approached me to try to discover his name and I said they’d have to speak to Kay. I didn’t hear from them again on that subject.

The Paquetá case

Returning to Lucas Paquetá, the FA apparently believe they have solid grounds for charging him with four counts of deliberately being booked, and two more of effectively failing to assist them in their investigation. And the player, it must be reiterated, insists he has done nothing wrong.

It is alleged he got himself booked on purpose against Leicester in November 2022, against Aston Villa in March 2023, against Leeds in May 2023 and against Bournemouth in August last year, on the opening day of the 2023-24 season. You can watch a video montage of those cards here.

The FA have handed long bans in recent years to players who have bet on themselves to get booked. Kynan Isaac, a defender with Stratford Town, got a 10-year ban for this in 2022. He had previously played for Reading and Luton. He was also banned for a further 18 months after being found guilty of placing, or enabling, almost 350 bets on matches. Under FA rules, footballers are banned from betting on any football match.

It is understood that dozens of people on Paquetá Island placed bets of between a few pounds and a few hundred pounds on one or more of the four yellow cards under suspicion. One irony in the case is that it was West Ham’s shirt sponsor, betting firm Betway, who spotted and reported the anomalous bets on Paquetá to be booked, that fuelled the FA’s investigation.

A twist in this tale is that one of Paquetá’s Brazilian compatriots, Luiz Henrique, was also the subject of bets that he would be yellow-carded while playing for Real Betis in Spain, against Villarreal, on the same day that Paquetá was yellow-carded against Villa in March 2023. He was.

It is believed that some bets placed on Paquetá Island were contingent on both of these events happening.

Theoretically, all these events might be a huge coincidence. In reality, a group of people knew in advance that these bookings were likely. At some point we’ll find out why the FA believe the latter explanation. You can bet on that.

Following last month’s investigative series on hyper-inflation in football ticket pricing (part one, part two and part three linked here), I’ve been working on the next series, which will use a data model developed for Lloyds of London - when Sporting Intelligence salary data was the key input - to predict the outcome of Euro 24. The model correctly predicted the winner of two of the last three men’s World Cups (it had England beating Brazil in the final in Qatar). The series will run for eight days from this Friday and be available in full only to paying subscribers.