Multi-club ownership in football is on the rise - and it's a financial and ethical minefield

European football is at the epicentre of a damaging trend that could destabilise the game

By Steve Menary and Nick Harris

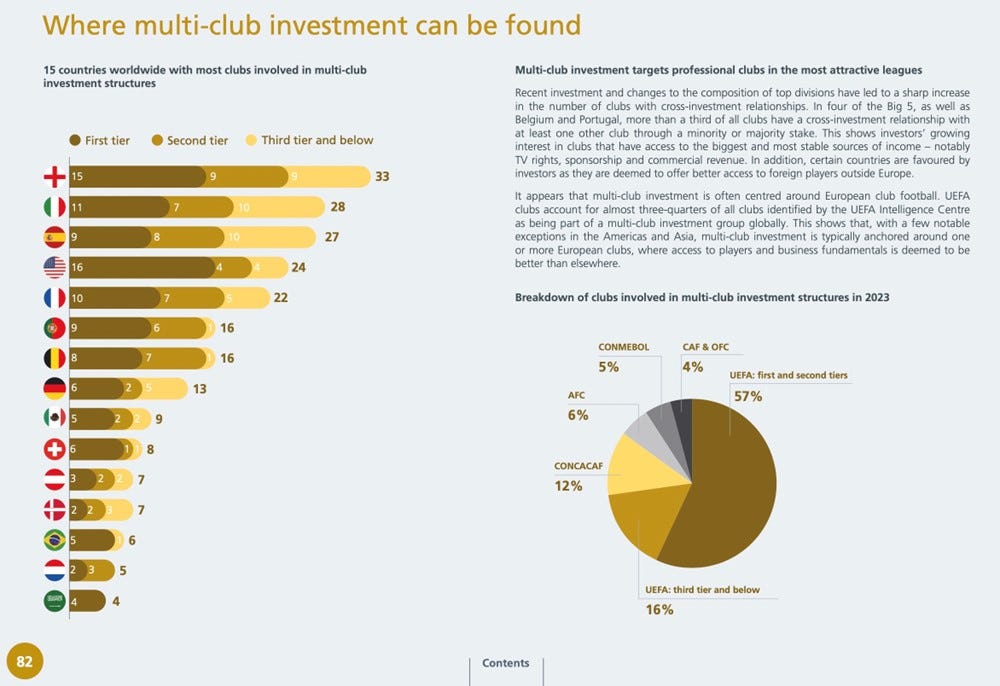

I read UEFA’s new benchmarking report on European club football over the weekend – there’s a news story on UEFA’s website, or get the report in full, now – and it contains a six-page section (pages 79-84) about multi-club ownership (writes Nick Harris).

The summary map is below, and when I tweeted about it, I was taken aback at the nearly unanimous negative responses to MCO groups in football. “Ban it”, “This sucks, man”, and a puke emoji; “Det här är helt galet. Fotbollen tar sig aldrig ur det här”, which translates as “This is absolutely crazy. Football will never get out of this”; and then the sarcastic “Healthy state of affairs”, with a thumb’s up emoji.

It seems obvious that there are multiple basic integrity issues at play – and not just the most egregious involving people who have attempted to establish match-fixing syndicates across clubs (more of which later), or want to launder money, or asset-strip.

There will, inevitably, be an increasing number of conflicts of interest as clubs in the same MCO group are drawn to face each other in the same competitions, for example European club football. But there are also problems with transfers and loans, and the stockpiling of players and fans' faith in why an owner wants their club.

Is it because they care about the club as a cherished local institution? Or because it’s a cog in a corporate machine, ultimately owned for the service of a bigger club higher up the food chain?

A former colleague, Rob Draper, considered one case study in this thread that perfectly illustrates how what’s important to fans is no longer a priority to some owners. Multi-club ownership groups will be motivated by different things: there may be a genuine desire to benefit from economies of scale, or a global scouting network with anchors in multiple continents, or a desire to lift standards across the board.

Meanwhile, over at the Red Bull group, the energy-drink firm with revenues of around €10bn in the last financial year, their acquisition of sports assets – including six football clubs in four countries across three continents – is ultimately about PR for their caffeine in a can.

When I was researching an MCO article last year, I was surprised to find that Ronaldo (the original Brazilian Ronaldo) owns two football clubs, and that Sheikh Abdullah of Sheffield United fame (who I’ve known for 11 years) owns five clubs.

But I was perhaps most surprised that Red Bull’s six clubs, combined, had cost them only around €56.4m in total to acquire or establish since 2005. That’s canny marketing and brilliant investing when you consider they now have clubs in the top divisions of Germany, Austria, the USA and Brazil, collectively worth many hundreds of millions, perhaps more than a billion.

Although MCO owners’ motivations differ, they will all, in the end, boil down to self-interest. This was obvious when the Premier League in England attempted to introduce a temporary ban for the January 2024 transfer window on loan deals between clubs with the same ownership. There was also a suggestion that certain cash-strapped clubs needing to inflate their income might sell players at inflated prices to MCO partner clubs overseas.

There was a vote in November 2023 and 14 votes were needed to prevent clubs making related-party loans, but only 12 clubs voted for the temporary block, with eight opting against it. Those eight opposing sides – Chelsea, Manchester City, Newcastle, Everton, Nottingham Forest, Sheffield United, Wolverhampton Wanderers and Burnley – were all either involved in, or on the verge of being, in MCO structures.

When I looked at the MCO situation last year and focused on the biggest group – and arguably the most successful – City Football Group, it seemed obvious that new FIFA rules put in place to prevent stockpiling players could easily be circumvented by MCO groups shifting their stars from place to place.

I pointed out to FIFA that their new rules had an apparently massive loophole. FIFA sources suggested multi-club groups are throwing up issues to which there are no easy answers. A spokesman said: “At this stage we are not in a position to discuss potential scenarios.” Or, in other words: “We have no answer to the problems MCOs create.”

My piece ran in the MoS last May.

The brilliant investigative reporter Steve Menary has tracked MCO activity closely over many years. I heartily recommend you follow him for his breadth of work in so many of football’s darkest corners.

Over to Steve now…

Three years ago, I started building up a list of clubs connected by joint ownership or with significant shareholders that have major stakes in other clubs (writes Steve Menary). By May 2021, I’d found 117 clubs involved in multi-club ownership (MCO) controlled by 45 different groups. Since then, MCO has ballooned.

In October 2021, the number of clubs had risen to 156 (in the first of two pieces for Play The Game). The growth continued but two-thirds of the 177 clubs identified by early 2022 — in this piece for Off The Pitch — were in a portfolio of just two teams. By November 2022, the MCO boom saw 227 clubs caught up in this network (in this piece for Josimar). That shot up to 256 clubs by March 2023, in a second piece for Play The Game.

UEFA, which in its 2023 benchmarking report had found 180 clubs in MCO, now reckons this network is more than 300, while The CIES Football Observatory believes the total is closing in on 350 clubs. In my own research, I’ve found 336 clubs – but does that mean the number of clubs in MCO has tripled since I first looked?

The size of MCOs is constantly shifting. I found one club had been sold only on writing this piece, reducing the total by one. Not every connection is immediately evident and, though not hidden, it is not advertised either. Identifying every club in the world with joint ownership is impossible, because some links are also clouded by opaque ownership structures. As a result, making year-on-year comparisons is maybe not wise, but without doubt MCO has boomed – and 336 clubs is really a minimum figure.

These stakes are held by 125 different groups or owners, and Europe is the focus, with 112 MCO groups featuring at least one European side. Much of the investment into MCO groups has come from North America, where owners also have significant interests. There are 32 MCO groups with one or more clubs in North America and 29 also have stakes in clubs in Europe. Overall, 79 per cent of clubs in MCO are in the UEFA and CONCACAF regions.

The focus of these MCO groups is mainly western Europe, where TV rights are stronger and can be quickly realised. “There’s a lot more low-hanging fruit in European football,” Jamie Dinan, founder of hedge fund York Capital, told the Financial Times last year.

Many of the clubs being bought up were hit by lack of match-day income during the Covid-19 pandemic. Financially weak clubs are vulnerable and those in western Europe also own their own stadiums, which provides some form of security. This is likely the reason that just 20 of the 217 European clubs in MCOs are in eastern Europe.

Most of these private equity or venture capitalist groups that are buying up the ‘low-hanging fruit’ will have an exit in mind before they bought their stake; that’s simply how that industry works. If the financial institutions cannot meet their own profit targets, then fire sales are likely; players will go, and sides will be relegated. This is why Football Supporters Europe also vehemently opposes MCO, as was abundantly evident when I spoke at their 2023 congress in Manchester.

Fans of clubs within networks that are deemed secondary to other clubs are despondent. No-one wants to think of their club as ‘low-hanging fruit’. Fans of Paris side Red Star, which is owned by controversial US investment group 777 Partners, are working with their local member of parliament on a bill to outlaw MCO. The Red Star ultras are trying to unite fans not just in their own country but elsewhere in Europe against what they call ‘timeshare ownership’.

I found 22 French clubs in MCO, which is the fifth largest behind England (32), the USA (30), Spain (28) and Italy (27). It’s hardly surprising that England has the most clubs in MCO as the Premier League is the richest football competition in the world but seemingly no keener on trying to properly regulate MCO than any other body in global football.

One impact of MCO not given much consideration is the vast amounts of players that are caught in these structures. In UEFA’s 2023 benchmarking report, around 6,500 players were estimated to be under contract at the 180 MCO groups identified in 2022. Applying that same metric to the latest figure suggests that more than 12,000 players are at clubs in MCO. No wonder the global players union FIFPRO has such serious reservations about MCO.

If a sizeable MCO group collapses, it could spark financial contagion with serious side-effects for players and clubs. There are 25 MCO groups comprised of four or more clubs. If one MCO of four clubs collapses and brings its network down, that would be – using UEFA’s metric – more than 140 players unpaid, let alone all the ancillary staff at clubs.

The other reason to fear the contagious impact of a major MCO collapse is money owed on transfer fees. The full price of a player transfer is rarely paid in one lump sum. Stage payments are common and can be underwritten by financial institutions as clubs wait on TV or other commercial income. Billions of pounds of transfer fees are due at any one time. If a big MCO goes down and all the clubs in its network cannot meet their financial obligations to other clubs, then there would be a serious domino effect. Clubs they owe money to will need that money to meet their own financial obligations to other clubs.

The integrity of football is at stake, although anyone attending one of the myriad sports business conferences and listening to so-called experts extol the virtues of MCO wouldn’t realise it.

If anyone doubts the seriousness of the problem, then consider one of the earliest and largest MCOs comprised of ‘low-hanging fruit’ in the Czech Republic, Latvia, Portugal, the Republic of Ireland, Romania and Spain. The man behind that MCO, Eric Mao, turned out to be assembling a network for match-fixing.

Think that problem has gone away? Then think again. At least one of the MCO groups identified in research for this article is controlled by someone who was censured for not reporting knowledge of match fixing. The opportunities for player trafficking and money laundering among networks of small clubs are also plentiful.

As ‘low-hanging fruit’ continue to be harvested across Europe, the consequences need considering not discounting.

Great article. It's crazy that it has been allowed to get this far, especially within Uefa. Very hard to see any roll back unless it's done by Governments through legislation forcing owners to divest interests in other clubs that are theoretically eligible for same competitions. Proper leadership at uefa could presumably push through meaningful reforms like a transfer ban between clubs but when has uefa had proper leadership.

Superb work, Nick and Steve. It is not so much the elephant in the room as a stampeding herd of pachyderms trampling everything in sight.