It's official: The referee's a homer, and 'Fergie-time' is a reality

.

In their “Freakonomics for sports” book, Scorecasting, Tobias J. Moskowitz and L. Jon Wertheim challenge conventional wisdom, uncover the hidden influences in sports and uses reams of data to investigate questions that tug at every fan. Are there really make-up calls in sports? Is there, in fact, a home field advantage? Is there really no ‘I’ in team? In the following excerpt, the authors—one a University Chicago economist, the other a writer at Sports Illustrated—consider how stoppage time in football favors the home team.

.

By Tobias J Moskowitz and L Jon Wertheim

25 June 2011

In football, the referee has discretion over the addition of extra time, referred to as “injury time,” at the end of the game, to make up for lost time due to unusual stoppages of play for injuries, penalties, substitutions, etcetera. This extra time is rationed at the discretion of the head referee and is not recorded or monitored anywhere else in the stadium.

As best he can, the referee is supposed to determine the accumulated time from unusual stoppages—itself a subjective measure—and add that extra time at the end of regulation. So does the referee’s discretion favor the home team? If so, he would lengthen this time when the home team is behind at the end of the game and reduce this time when they are ahead—extending or shortening the game to increase the home team’s chances of winning.

Using handwritten notes that his elderly mother had gathered logging matches she’d watched from her living room in Spain, Natxo Palacios-Huerta, a London School of Economics professor, joined with two colleagues from the University of Chicago, Luis Garicano and Canice Prendergast—all football fanatics—to study the officials’ conduct during games. The researchers were, quite justifiably, struck by what they found.

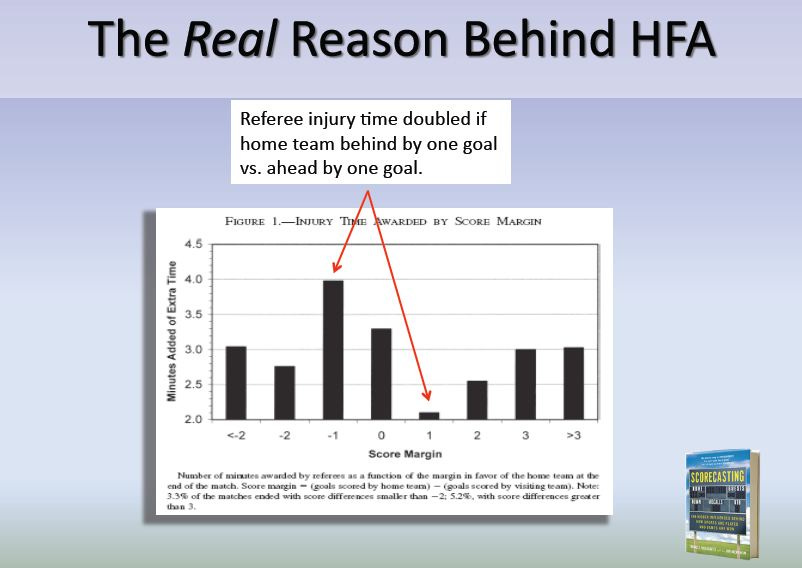

Examining 750 matches from Spain’s premier league La Liga, they determined that in close matches with the home team ahead, the referees ritually shortened the game by reducing significantly the extra time. In close games in which the home team was behind, the referee lengthened the game with extra injury time. If the home team was ahead by a goal at the end of regulation, the average injury time given was barely two minutes. But, if the home team was behind by a goal, the average injury time awarded was four minutes; twice as much time! And, sure enough, when the score was tied, and it wasn’t clear whether to increase or decrease the time for the home team, the average injury time was right around three minutes. (See graphic below)

What happened when the home team was significantly ahead or behind? In games that were not close, there was no bias at all. The extra time added was roughly the same whether the home team was ahead by two goals or more or behind by two goals or more. This makes sense. A referee has to balance the benefit of any favoritism he might apply with the costs of favoritism—harm to his reputation, media scrutiny, and potential reprimand. Adding additional injury time when the score was so lopsided was unlikely to change the outcome and therefore accrue much benefit. So why do it and risk the potential cost?

The study also looked at what happened when, in 1998, the league altered its point structure from awarding teams two points in the standings for a win (and one for a draw and zero for a loss) to three points for a win. This change meant that a win was suddenly worth a lot more than it was before and the difference between winning and tying doubled. What did this do to the referee injury time bias? It increased it significantly. In particular, preserving a win against a tie now meant a lot more to the home team, and so the referees adjusted the extra time accordingly and more significantly to reflect those greater benefits.

And this wasn’t unique to Spain. Researchers began looking for the same referee biases in other leagues—not hard given the global popularity of football. They found that the exact same injury time bias in favor of the home team exists in the English Premier league, the Italian Serie A league, the German Bundesliga, the Scottish league, and even in MLS in the United States.

If referees are willing to alter the injury time in favor of the home team, what else might they be doing to help ensure that the home crowd leaves happy? We found that referees also award more penalties in favor of the home team. Disputed penalty shots and goals tend, disproportionally, to go the home team’s way as well.

Looking at more than 15,000 European football matches in the English Premiere, Spanish La Liga, and Serie A leagues, we found that home teams receive many fewer red and yellow cards—even after controlling for the number of penalties or fouls of both teams. And the dispensing of red and yellow cards has a large impact on a game’s outcome. A red card, which sends the offending player off the field, reduces a team’s chances of winning by more than seven percent. A yellow card, which precedes a red card as a stern warning for a foul, and may therefore cause its recipient to play more cautiously, reduces the chances of winning by more than two percent.

These are large effects. When a single yellow card, followed by a red card, is given to a visiting player, it means the home team’s chance of winning, absent any other effects, jumps to 59%. Add the injury time, fouls, free kicks…. and it suddenly isn’t so surprising that the home team in football wins nearly 63% of its games.

.

More details on Scorecasting

Sportingintelligence home page

.