INTERVIEW: "I was offered millions to tell everything I knew about Beckham to the papers"

'It's Jerry Maguire meets The Wolf of Wall Street' - and the cast includes a drug cartel, Brian Clough, Rebecca Loos and Ange Postecoglou. This is the incredible story of Andy Bernal

Andy Bernal was David Beckham’s right-hand man at the height of Beckham’s fame, and had a front-row seat to the most notorious episode in the private life of the former England captain.

Speaking to the former Australian international, 57, earlier this week, he told me: “My life’s been like a movie when you put it together, like a cross between Jerry Maguire from my [post-playing] agent days, then The Wolf of Wall Street, and people going insane on drugs, with a bit of James Bond thrown in from my time with Beckham.

“If a Hollywood producer decided to turn it into a movie, they’d need some budget for the scenes in Madrid alone. Helicopters chasing us across the city. Getting mobbed wherever we went. Throw in the fact you’ve got a Spice Girl involved, Victoria being one of the world’s most famous women at the time.

“It was a time of insanity and madness, the sheer attention with the newspapers trying to get any tiny thing they could, relentlessly.

“As for my time with David himself, I enjoyed it. I was his right-hand man and friend. We’d go to parties at Ronaldo’s house, the original Ronaldo, and there was also Roberto Carlos in that team, and Zidane and Figo and Raúl and Casillas.

“I was protective of him. There were periods at that time and after when I was offered millions - literally millions - to tell everything I knew to the papers. And that didn’t happen.”

Last summer at the Football Writers’ Festival in Australia, I was the compere for an evening event at a Sydney theatre where Andy was a panellist and he told an anecdote about the Beckham era in Madrid that had the audience in awe, and hysterics, for almost 20 minutes, more of which shortly.

Most recently his career has seen him in the role of Head of Athletic Development, (aka “The Vibe Manager”) at the Central Coastal Mariners as they won the A-League title in Australia last season.

As a player, Bernal was the first Australian to sign for a La Liga club (Sporting Gijon, in 1985), then persuaded Brian Clough to give him a trial at Nottingham Forest after walking in off the street in 1987.

That was after he fled Spain because he was about to be called up for military service (he was born in Canberra, Australia of Spanish parents and was a dual Australian-Spanish citizen).

Clough played Bernal in the Forest reserves early in the 1987-88 season when Bernal was 21, but couldn’t promise him first-team football and instead helped him to get a contract at Ipswich, then in the second tier.

“Seeing how Clough mentored men is embedded in my brain,” Bernal tells me, after explaining how he researched when and where Forest would be training in pre-season that year.

He turned up and approached one of Clough’s coaches, Archie Gemmill, in the car park, and asked him to tell Clough he wanted a trial. Clough gave Bernal an opportunity to plead his case: they had a long conversation about cricket, a mutual passion, and Clough then asked Gemmill to provide Bernal with some kit.

Bernal impressed Clough, and then played reserve football for a few months for Forest before Clough pulled him aside and told him that he was unlikely to get a chance because Neil Webb and Des Walker excelled in positions he could play.

Clough, with his Labrador by his side, as was usual at the time, asked Bernal if he would be happy to be recommended to another club, specifically Ipswich of the second tier, who were “looking for a No.6”.

Bernal said yes and recalls: “Clough created a culture that in turn created good humans and good professionals … he couldn’t offer me a place at Forest but he called the Ipswich manager John Duncan, found me an opportunity and put me on a train”.

Bernal played that Spring, in 1988, for Ipswich, and was offered a three-year contract at Portman Road, then went back to Australia on holiday for six weeks.

Arriving back at Heathrow, he was, to his dismay, deported because he had been playing professional football for Ipswich when his visa only entitled him to hold a part-time job.

Did I mention, by the way, that after Bernal returned to England almost five years later (in 1994) and after he became captain of Reading during a six-year spell in the Championship (to 2000), he became addicted to crack cocaine and lost 10 to 15 years of his life in a blur of that addiction?

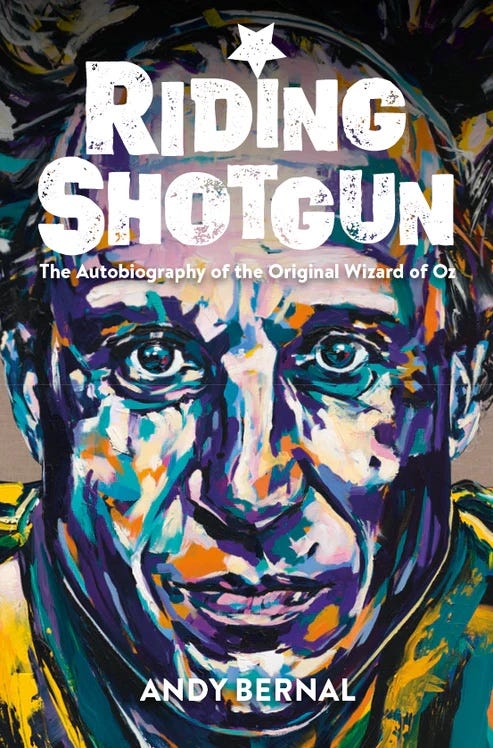

You can read all about this in Bernal’s hugely entertaining 2021 autobiography ‘Riding Shotgun – The Original Wizard of Oz’ and follow the journey of his recovery via his second book ‘The Vibe Manager: an inside look at the 2023 A-League Champions.’

Bernal had a 15-year professional playing career despite being born with a defective left leg, almost devoid of medial and lateral cartilage, and with a patella (kneecap) that did not function as normal. He had eight knee operations during his career.

He was a contemporary of Ange Postecoglou as an up-and-coming Australian player in the 1980s. Bernal is 57 and Postecoglou is 58.

He says of Postecoglou now: “Ange is amazing and pioneering and opening the doors for Australian coaches. He’s the flagship.”

Bernal recalls an incident when Postecoglou was the manager of Australia’s men’s international team between 2013 and 2017 and Bernal was just a fan again, albeit a shell of his former self in the grip of addiction.

“There were a couple times during my cocaine years where I was just ashamed and embarrassed to be seen in public,” he tells me. “I went to a Socceroos match as a fan and sat in the stands.

“Ange came out the tunnel not far away from me and I just yelled ‘Hey Ange’.

“And he saw it was me, he came over, the manager of Australia, and he gave me a hug.

“I was a mess, an addict in a cap, who had wrecked his life, and Ange just gave me a hug, looked me in the eye and said ‘You ok, mate? Is there anything I can do for you?’ And he meant it.”

Nobody who was at the event at last summer’s Football Writers’ Festival will forget the way in which Bernal ended the evening with an astonishing anecdote.

The premise of the evening was that we were now in 2034, or 11 years into the future, and I had set out a raft of hypothetical propositions about how the world, and the football world, had evolved.

One of my ridiculous propositions was that Saudi Arabia was about to stage the 2034 men’s World Cup. Ahem.

Other propositions considered the balance of power between FIFA and UEFA in 2034, and whether nation states would be dominating club football, and the extent to which AI and multi-club ownership would be preeminent.

I had opened the evening’s proceedings by asking all the panellists about how their love of football began, and what, if anything, they feared about the future of the game.

Andy Bernal had talked about his love of football stemming from the physical act of kicking a ball, when playing football was a distraction from the chaos of his childhood.

I knew Andy had great stories to tell, so I ended the evening by asking him to tell the audience about any point in his life - with all its ups and massive downs - when he thought: “How on earth did I get here?”

I had not discussed this with him prior to us going on stage. I had zero idea what he was about to say. But off he went, telling a story that had us all in the palm of his hand for the rest of the night.

I’ll abbreviate it here. When Beckham was in Madrid and Bernal was his right-hand man, they had a weekend visit from mutual friends in the music industry. Those friends requested that “party enhancers” were in place when they arrived.

Bernal knew a lot of people in Madrid in the world of entertainment, and the world of those who provide, for want of a better word, “services” to the world of entertainment. One of them was a former spy for Cuba’s counter-intelligence service who was now running a bodyguard business in Madrid and was well connected to various Colombian providers of “party products”.

Bernal drove to a Madrid mansion where he was told he’d be provided with a large bag of “marching powder” and enough weed for a weekend of visitors. Armed guards greeted him. He was given a holdall with the gear. The story involved a stop by traffic police and a let-off after Bernal explained he was Beckham’s minder and handed out a signed Real Madrid shirt from a box in the boot, kept there especially for such events.

“On more than one occasion, quite a few occasions actually, a signed DB shirt got us out of a situation,” Bernal tells me.

The story also involved Bernal driving a sports car that had been leant to him for nothing. “There were days we were there and I was walking around thinking ‘I’m in a movie here’. I could go to a Porsche showroom and because I was David’s minder I could drive away with any car I wanted.”

And it involved him stopping on the way back to deliver the “party materials” so he could snort a line of coke from the car’s dashboard, outside the Bernabéu, the home of Real Madrid, aka ‘The Whites’.

We don’t need to delve into the personalities implicated in that weekend, although Bernal did have to explain to Beckham that he’d need to meet a contact and his son for breakfast in return for the contact’s help with the party supplies. (It’s what the contact wanted, he really, really wanted. Zigazig, ah).

Of much greater significance during Beckham’s time in Madrid was the player’s affair with his personal assistant, Rebecca Loos, of the management agency SFX.

Bernal was introduced to Tony Stephens, the hugely powerful agent in the SFX world, by a mutual friend, Sue Roberts, who he knew during his time at Reading. Bernal was thinking about his post-playing days by mid 2000, aged 34, and Roberts arranged an appointment between the pair.

“If you last more than five minutes, you’ll be in,” she told him. Bernal took a train up to London from Reading and walked into the Mayfair offices of SFX, where posters of their superstar international clients adorned the walls: Beckham, Kobe Bryant, Michael Jordan.

Stephens called Bernal in, and after more than an hour, Bernal’s role as an SFX agent was effectively a done deal.

He had experience as a footballer, was multi-lingual, was street smart, and had a wide array of contacts, in Australia and Spain.

SFX at that point were trying to sign an up-and-coming Australian footballer star, then a 20-year-old player at Millwall. Within a week Bernal had Tim Cahill in SFX’s office and became the player’s agent, and an SFX agent, and his career took another turn.

Bernal was sent to Italy and Spain for a couple of years to develop contacts, and then to Madrid with Beckham, after months spent in the city preparing his arrival.

Bernal is scathing in his first book about SFX’s logic in appointing the attractive, and single, Loos as Beckham’s personal assistant.

This week, Bernal told me: “Appointing Rebecca as Beckham’s personal assistant was the worst decision by any management agency in the history of sport.”

Beckham and Loos had an affair that year in Madrid. It was, later, widely reported and never expressly denied by the Beckhams.

Bernal has never spoken about that, and still doesn’t.

Loos sold her story to the News of The World and Sky News in early 2004, reportedly for hundreds of thousands of pounds.

Loos told Sky’s Kay Burley that Beckham was an “amazing lover” and they “couldn't keep their hands off each other”.

The Beckhams, in an excruciating media campaign, said the allegations were “absurd”, “ludicrous” and “unsubstantiated” while not actually saying they were untrue. And they didn’t sue anyone.

Beckham announced in October 2003 that he was splitting with SFX. The affair with Loos was not public then and it was claimed that Beckham was leaving because he wanted to scale down his commercial activity.

“SFX London had to tell SFX USA that they’d lost the biggest marketing phenomenon in global sport,” Bernal now says.

The personal ramifications for Bernal were huge: he had no idea how his future with SFX would work out (it wouldn’t), and then spent time in Madrid and Australia and then London getting deeper and deeper into a major drug habit.

Cocaine had been a recreational drug at points but the SFX situation deteriorated - they tried and failed to get him to sign a confidentiality agreement months after leaving Madrid - and they parted ways.

“I got into a hole and into depression. And drugs - lots of drugs,” he says. “I stayed in Reading and couldn’t get hold of powder one night so turned to crack.

“Crack is a destroyer of entire neighbourhoods in the US, a wrecker of lives.”

His own life, on drugs, in crack dens in Reading and London, was wrecked, he estimates, for 10-15 years.

As he wrote in his first book: “Once I discovered the crack cocaine houses in Reading and London, they strangely became attractive, warm, and inviting. These squalors, that were guilty for the destruction of human beings, both physically and mentally, I found quite normal during this period of my life.

“Normal people, now junkies, living in filthy sub-human conditions were commonplace, and to think I would drive past these places, many times on my way to football matches, thinking: “How the f*** can people live there?”

Redemption came in recent years when a businessman, Richard Peil, read Bernal’s first book, and called him for advice, and then became chairman of the Central Coastal Mariners, and employed a reformed Bernal as Head of Athletic Development ahead of the 2022-23 season.

Nick Montgomery was the manager who led the side to the Grand Final win last season. The 42-year-old former midfielder and Scottish Under-21 international spent 12 years at Sheffield United from 2000-12, then played for the Mariners for five years until 2017, before returning to manage them from 2021 to 2023. He is now manager at Hibs in Scotland.

It was ‘Monty’ who gave Bernal his nickname of ‘The Vibe Manager’ at the Mariners. Bernal describes himself now as “a lieutenant” to both the Mariners’ head coach Mark Jackson, and strength and conditioning coach Brice Johnson,

It is clear now, having researched Bernal’s role at the club, that he was hired as, and remains, a talisman, a voice of experience, a walking and talking cautionary tale, a lesson that you can achieve, and overcome adversity.

The Mariners won last season’s A-League Grand Final, an historic achievement. Bernal says: “Winning the Grand Final versus the City Group-owned Melbourne team was a fantastic achievement. And we smashed them 6-1 in the final. They’ve got some of the richest owners anywhere and we were constantly fielding the youngest starting XIs in the league and operating on the lowest budget.

“And now this season we have another extraordinary football department, also doing well.”

At the time of writing in mid-March, the Mariners are sitting top of the A-League after 21 games, ahead of second-placed Wellington Phoenix on goal difference and six points clear of Melbourne City in third.

“I’m still learning all the time,” Bernal says. “I’m mentoring young men. A lot of my role now is mentoring people with my story.

“I love being around the boys, and working on fitness, strength conditioning, motivation, speaking Spanish, Portuguese, Italian.

“We produce good athletes who produce great numbers. And we create and empower these machines.”

I remind Bernal about the ovation he received last summer, in a Sydney theatre, after his extraordinary story about a Madrid night many years ago, and the affection in which he is held. He pauses, then says: “Not many people come back from crack cocaine addiction.”

Never thought I would see a story involving Andy and my tiny local club in Australia! Cracking stories 😉