Scottish football's Millennium bug: frozen spending, then a cross-border chasm

As English Premier League clubs smash their transfer records this summer, only two from Scotland's top division signed their most expensive player after 2001

This piece was commissioned for the new Nutmeg Substack and I’ll be writing for Nutmeg once a month. Those pieces will appear here, and over there. More about Nutmeg later.

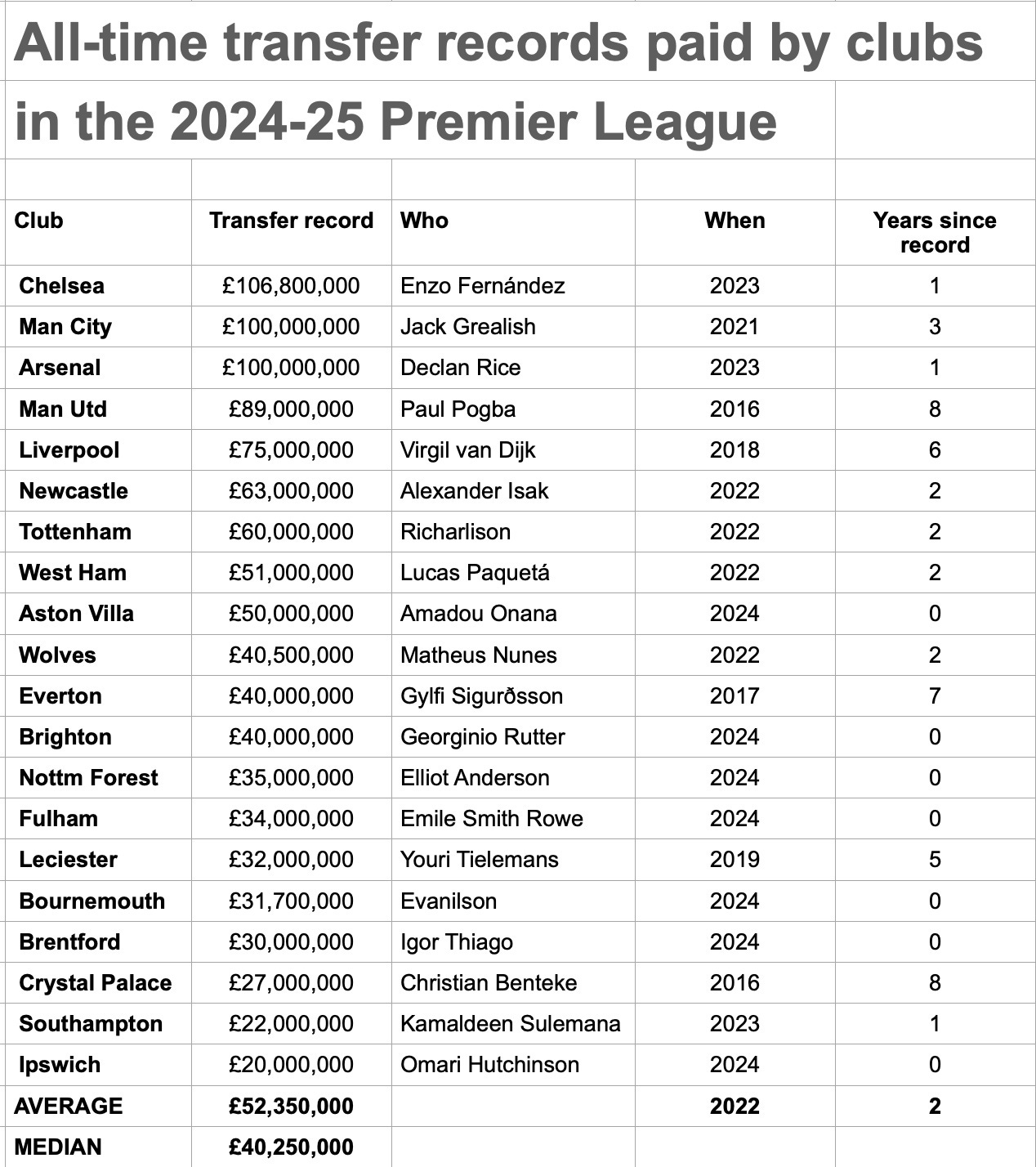

Seven of the 20 clubs playing in the English Premier League this season have broken their transfer records this summer. They range from Aston Villa, who spent £50m on Amadou Onana from Everton, to Ipswich Town, who spent £20m on Omari Hutchinson from Chelsea.

The largest sum ever spent by any club in Scotland for a single footballer was £12m, paid by Rangers, 24 years ago in 2000, to Chelsea for Tore André Flo. At the time that wasn’t far behind the record fee ever paid by a British club to sign a player, the £15m Newcastle paid for Alan Shearer in 1996.

In hindsight it seems fitting that the year 2000 was when Scottish spending hit that peak, because it turned out that the game north of the border had caught a Millennium bug. It would leave clubs reeling, trailing in the wake of their English counterparts.

The Scottish club game didn’t so much stand still as go backwards. The differences today between England’s elite and Scotland’s are gargantuan, financially at least. We’ll return to some possible reasons for this shortly, but first some illustrations of that gap.

On average, the current Premier League clubs in England set their transfer fee records less than two years ago. Aside from the seven clubs setting records this summer, three others set theirs in 2023 and four more set theirs in 2022. It’s only the relatively old records of Crystal Palace and Manchester United (both set eight years ago), Everton (seven years ago) and Liverpool (six years ago) that make the divisional average as big as two years.

Chelsea’s record fee, of £106.8m last year for Enzo Fernández, is the current PL record fee paid, but the average record fee of the 20 clubs is £52.35m and the median record is £40.25m, the latter more than three times as much as the £12m all-time record in Scotland.

Here are the details from England, although some might have changed in the hours since this was written!

As for Scotland, among the 12 clubs in this season’s Premiership, their average transfer record is £2.27m and the median record is £650,000. Their record fees were set an average of 23 years go, just after the Millennium.

Only three of the clubs paid more than £1m for their most expensive player: Rangers for Flo, Celtic for Odsonne Édouard (£9m in 2018) and Hearts for … John Robertson (£1.5m in 1988).

Below are all the details. Note that transfer fees paid are rarely confirmed, on the record, by football clubs, unless there is an obligation to report them to the local equivalent of the Stock Exchange for regulatory purposes, as happens much of the time in Portugal and the Netherlands.

Multiple sources, for example, say John Robertson was Hearts’ record signing at £1.5m (or £1.35m) but other sources say £750,000. One source close to Hearts has said Mirsad Bešlija is Hearts’ record signing, costing £850,000 in 2006. The graphic below has been amended from the original to reflect that.

Another indicator of Scotland’s economic stasis in football is wage growth, or rather relative lack of wage growth. In the 1998-99 season - when Manchester United won the Treble, capped by that astonishing last-gasp win in the Champions League final - the top five wage payers in the whole of British football, were, in order, Manchester United, Liverpool, Rangers, Arsenal and Chelsea.

Rangers had a bigger wage bill than the teams who finished second and third behind United in the Premier League that year (Arsenal and Chelsea), and bigger than the runners-up in that season’s FA Cup final (Newcastle).

As of the most recent season for which full club accounts are currently available, 2022-23, Rangers’ wage bill had just about doubled in the intervening 24 years, or to be precise, grown 101%.

What about other big British clubs? It’s staggering.

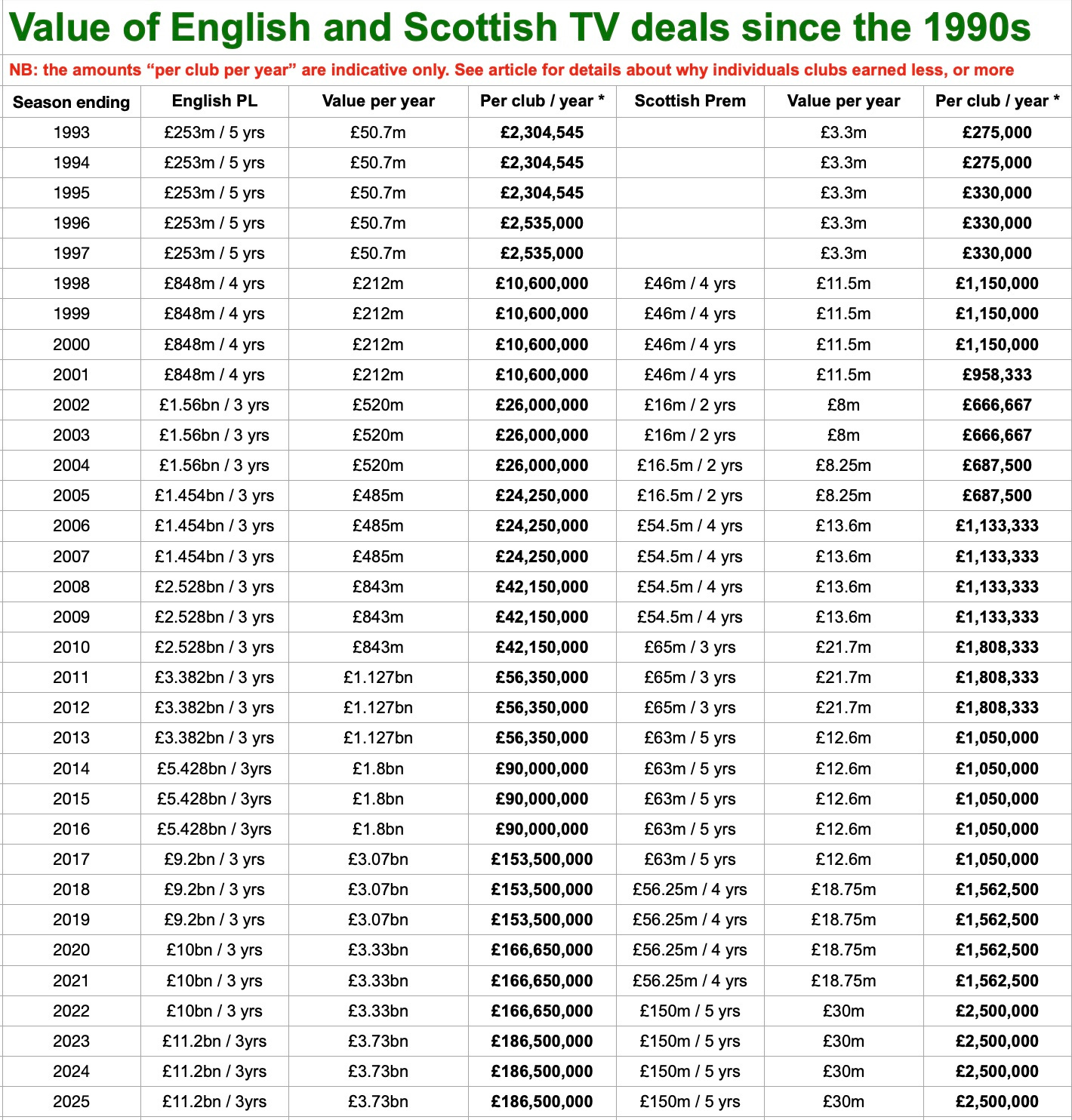

The reason the Premier League clubs in the table above have been able to afford such huge wage bill increases is because the PL’s TV revenues have grown exponentially since the English top division was revamped from the 1992-93 season.

Back then, total PL TV revenue per year (domestic and foreign combined, although there was hardly any foreign TV cash) was £50.7m a year. That’s for all 22 clubs combined.

By this season, 2024-25, that has become £3.73 BILLION a year, to be shared between the 20 clubs, or the thick end of £3bn anyway, after giveaways to lower divisions and league running costs have been deducted.

In Scotland, meanwhile, the 12 clubs in the top division in 1992-93 were sharing £3.3m a year, or about a tenth of the amount per club that the PL clubs were getting. By the mid-Noughties the Scottish clubs were getting one twentieth of the TV cash of the PL clubs and by 2020 it was about one hundredth of the PL clubs.

The detail is in the graphic below but please note that the “per club per year” figures are indicative only - they don’t apply to every club in each league in every season.

Firstly, the leagues received the “value per year” amounts but running costs for those leagues and handouts to other teams lower down the pyramid are deducted before the remaining money is divided between the top-flight clubs.

And the best performing clubs get more than those doing less well. The overall picture is clear however.

It wasn’t long after the Millennium that Sky Sports, who were paying £11.5m a year to screen Scottish top-flight games at the time, made an extension offer beyond 2001 at the same annual rate. It was rejected by the league because the SPL believed they could attract a lot more money.

If you’re interested in the fine detail of that episode and some of the ramifications, then it was explored in great detail in the first ever edition of Nutmeg back in 2016, and you can read that story online here. Another piece on a different site explores the contrasting paths that the Premier League and SPL took after their formations.

When the SPL rejected Sky’s extension offer, they failed to get a more lucrative one and in fact had to settle for a lower amount, which is when Scottish clubs - already walking a financial tightrope - started to struggle with debt and making ends meet.

Motherwell were the first SPL club to enter financial administration, in April 2002, with debts of £11m and a wage bill close to 100% of their revenue.

Dundee followed suit the following year, laying off dozens of staff after debts hit £20m. Livingston followed in 2004, while Dunfermline, Hearts and Hibs also had rocky years ahead. Even Rangers by 2004 were planning a rights issue to raise £57m in attempt to clear enormous debt.

By then, the Premier League had agreed back-to-back three-year TV deals worth £1.5bn. They had clear financial water between themselves and their richest rival leagues in Spain, Germany and Italy, let alone their neighbours to the north.

Yet some of Scotland’s clubs have experiences in their histories that most of England’s elite have never had. Celtic have a European Cup win in their history. Aberdeen have beaten Real Madrid to win a European trophy.

Rangers have also won the Cup-Winners’ Cup, and have been runners-up in five other European competitions, including in the UEFA Cup / Europa League finals of 2008 and 2022.

Dramatic changes over time don’t all have to go one way.

The new Nutmeg Substack offers brilliant football writing, made in Scotland, with all the content currently available free to all subscribers. Nutmeg also continues to exist as a hard copy quality Quarterly, published four times a year since Autumn 2016. More information on that here.

Thanks for linking to my 2016 Nutmeg piece, Nick. A great publication made by good people.

Great article. I'd like the gulf in footballing success to be explored deeper. My perception is that Scotland has fallen further behind.