For a sport so dedicated to statistics, cricket's darkest numbers are misleading

It's been widely accepted for several decades that cricketers, not least Test stars, are more prone to suicide than players in any other sport. Except it's not true...

I was de-cluttering the sports books in my office the other day, hoping to reduce the number from 1,000 to about 500 to make room for other stuff.

Making “keep or go” decisions about various cricket titles - from random editions of Wisden to historical tomes about the game in the 19th century - bought for research purposes for a biography of Billy Midwinter that I’m yet to write - in quick succession I came across Silence of the Heart: Cricket Suicides by David Frith, and Rising from the Ashes by former Surrey and England cricketer Graham Thorpe (below).

For obvious reasons, that gave me pause for thought. Frith’s 2001 title has been described as “a startling investigative narrative covering the phenomenon of cricket's unduly high level of suicide.”

The autobiography of Thorpe is his brutally honest life story, including, in his own words, descriptions of periods of suicidal depression. He took his own life on 4 August this year.

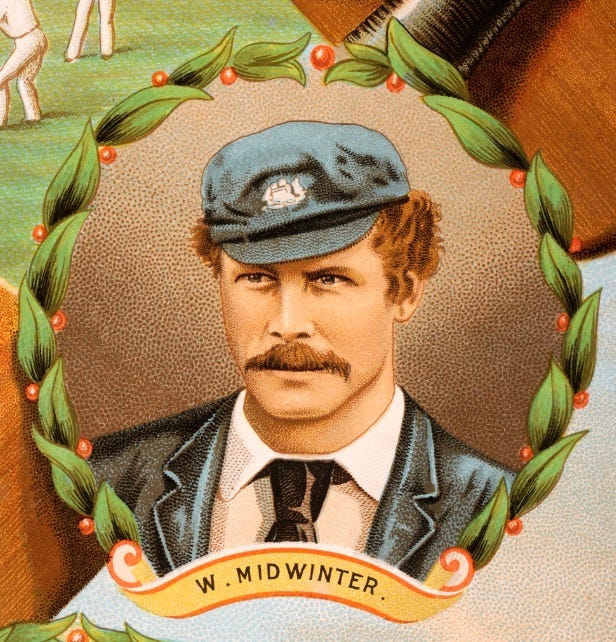

Billy Midwinter had his own mental struggles in his post-playing days. I was drawn to his story a long time ago, and not just because he remains the only man to have played in the Ashes both for Australia against England and for England against Australia.

Born in England in 1851, he made his name in Australia, where his family had moved when he was nine. His father emigrated to join the gold rush in Bendigo Creek, in northern Victoria.

Billy blazed a cricketing trail from Outback prodigy to record-breaking teenager. He changed the ethos of his sport, becoming the world's first transoceanic professional player and a cricketer of such prowess that the legendary W G Grace once resorted to “kidnap” him to secure his services.

The latter years of Billy's life were as eventful as the rest, but tragically so. His eldest son, William, was a sickly child and was later to die aged 12. His daughter, Elsie, died of pneumonia in November 1888, aged 10 months. His wife died of apoplexy in August 1889 and then his second son, Albert, died aged three in November of the same year.

After the deaths of Lizzie, Elsie and Albert, Billy (below) was declared insane. He was committed to the Kera Asylum in Melbourne on 14 August 1890 suffering from a "depression" that left him paralysed. He died at 11am on Wednesday 3 December, 1890.

He was the first Test cricketer to die. I wrote about his extraordinary life for The Independent back in 2001.

A decade later, in 2011, after the former cricketer and writer Peter Roebuck took his own life, I started to delve into the supposed phenomenon of suicides in cricket.

Could cricket really play any role in a man deciding to end his life?

Frith, now 87, is an author, historian, former editor of The Cricketer magazine and the founding editor of Wisden Cricket Monthly.

He explored cricketer suicides in two books, By His Own Hand in 1991, then Silence of the Heart in 2001, written in partnership with the former England cricket captain turned psychoanalyst Mike Brearley.

The first book chronicled the lives and deaths of 80 cricketers who killed themselves, or are believed to have killed themselves.

By the second book, Frith had amassed details of 151 cricketing suicides, among them 23 Test players. Of those 23 players, six were men who had played Test cricket for England.

I rang Frith in 2011 and he told me that he set out with the intention of trying to “get cricket off the hook” for this appalling loss of life; that he wanted, through his research and the exploration of individual sportsman’s lives, to show that actually, and possibly always, they killed themselves for non-cricketing reasons.

Some of the 151 had long-standing depressive illnesses and mental health issues. Others had been left devastated by marital break-ups, financial problems, terminal illness or other incapacity. Many of them took their lives in the gloaming years when the thrill of competition was gone and middle age was setting in.

Over time, Frith told me, he had been left in no doubt that something about the life of a cricketer affects some men. “It’s a creepy game,” he said. “And I should know because I played it for 50 years. And the statistics are there that show there is an issue.”

This is where my own analysis diverged from Frith, a world expert in this field. Ironically, given cricket’s extensive usage of statistics, it is statistics that I believed failed to make the case for a definitively stark link between suicide and cricket.

To my knowledge – and to Frith’s knowledge – there had never been any large-scale, statistically relevant study of the relationship between professional cricket and suicide, or indeed suicide and any one sport.

Frith’s own work was the most extensive in the field, and as he himself readily conceded, “it would take 20 of me” to compile the large amount of information to reach firm conclusions.

That didn’t prevent a headline-grabbing statistic, arising from Frith’s 2001 book, from making in into the national and international media. It was the claim that English cricketers are "almost twice as likely to commit suicide as the average male".

This was based on two statistical ‘facts’:

That suicide accounted for 1.07 per cent of British male deaths.

That the rate among English cricketers is 1.77 per cent.

There were problems with both these claims.

Firstly the 1.07 per cent (based on 1998 UK data) was wrong, for reasons that Frith is not sure, but perhaps because inaccurate information was provided in the first place.

The Office for National Statistics website has a free database that carries all the relevant information, much of it available to download in searchable spreadsheets. And a search in 2011 showed there were 264,707 male deaths in the UK in 1998, of which 4,039 were suicides, which equates to a 1.53 per cent male suicide rate in the UK in 1998, not 1.07 per cent.

Secondly, that 1.77 per cent rate of suicides among English Test cricketers was arrived at by looking at 339 English Test cricketers – across all time – who had died by July 2000. Six of those 339 (or 1.77 per cent) had killed themselves.

To base any fixed conclusion on such a tiny sample pool of a few hundred people spread over more than a century is risky. The data pool is just too small to be statistically reliable.

Then consider the individual cases of the six men who killed themselves. They were:

William Scotton (died 1893, age 37, after suffering depression).

Andrew Stoddart (died 1893, age 52, after falling into bad health and debt. He shot himself).

Arthur Shrewsbury (died 1903, age 47, after shooting himself in the mistaken belief he was terminally ill).

Albert Relf (died 1937, age 62, following depression).

Harold Gimblett (died 1978, aged 63, who overdosed on prescription drugs after years of mental health problems)

David Bairstow (died 1998, aged 46, hanging himself a few weeks after surviving an overdose. He’d suffered from depression. The coroner actually returned an open verdict, not convinced of true intent of suicide above a “cry for help”).

The tragic cases of these six men, three from Victorian times, but all with depressive histories and / or health and financial worries in their post-playing days, were the basis of the “English cricketers twice as prone to suicide” claim.

In fact, had there been five of them and not six (if you did not count Bairstow, where the coroner did not record suicide), that would have been 1.47 per cent of the 339-man sample pool, and hence a lower figure than real 1998 British rate of 1.53 per cent of male deaths by suicide.

English cricketers might easily have been presented as less susceptible to suicide than the typical person.

This is not to disparage Frith’s work in any way because the incidence of suicide by players of other Test nations was apparently high by 2001: a startling 4.12 per cent in South Africa, 3.92 per cent in New Zealand and 2.75 per cent in Australia.

But again, the sample pools are small, statistically insignificantly small, and most of the cases, like those involving English cricketers over vast stretches of history, are not obviously connected to the business of playing cricket.

That South Africa figure is based on seven deaths, the Australian figure on five deaths and the NZ figure on two, one of them by somebody with terminal cancer.

It should also be noted there has never been a confirmed suicide of any Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan or West Indies Test cricketer, of any era, which might lead to the assumption that Test cricketers in those countries are wholly immune from the phenomenon. That wouldn’t be a statistically valid conclusion any more than saying English cricketers are twice as likely to die at their own hands as “normal” English people.

Somewhere in the region of 2,700 people had ever played Test cricket by 2011. The 23 suicides identified by Frith by 2001 equate to a rate of 0.85 per cent of that total. To be necessarily macabre to illustrate a point, there need to be almost as many suicides again amongst living Test players (at any stage of their lives) for the universal Test player suicide rate to become even slightly “abnormal”.

Professor John Aggleton was a specialist in behavioural neuroscience at Cardiff University’s School of Psychology in 2011. In 1994 he co-authored a paper (linked here) on the differing life spans of right-handed and left-handed people, and used cricketers as his research pool because there was a clear record of handedness for the individuals.

The study involved a Who’s Who (literally) of first-class cricketers, 5,479 of them, of whom 3,165 had died.

Unfortunately, that data pool is too unreliable in terms of causes of death to assess the significance of suicide in cricketers, but Prof Aggleton did offer a theory as to why a perception of high suicide rates in cricket could endure even without any significant data to back it up.

“In psychology there is a term known as the availability heuristic,” he told me. “This is where something seems common because an example comes to mind readily, rather than because it is actually common.”

In other words, the death of a well-liked public figure such as Bairstow in 1998, and of a well-known writer such as Roebuck in 2011 provoked a link in the public consciousness between cricket and suicide – but it might well be illusory.

And when we heard about the troubles of cricketers from Marcus Trescothick and Michael Yardy to Jonathan Trott and Ben Stokes, it is all too easy to assume there is some oddly irregular relationship between their sport and mental health.

But perhaps there isn’t. Perhaps depression and its most dire consequences aren’t any more oddly common or uncommon in cricket than anywhere else. Just because we’re not hearing that Fred from the car factory or Tom from the local solicitor’s office is off work with long-term depression and we’re not seeing news of Bob the local butcher’s suicide in the paper doesn’t mean they’re not happening.

There might even be a case for saying that it is counter-productive – perhaps even self-fulfilling – to draw conclusions on cricket and suicide on partial evidence.

Does cricket have any more significant link to suicide than football?

German goalkeeper Robert Enke killed himself in 2009, the year after English goalkeeper Tim Carter killed himself and the year before Dale Roberts, a goalkeeper with Rushden & Diamonds, took his own life. Three goalkeepers in three years: how freaky is that? Probably not freaky at all. Justin Fashanu killed himself, as did Dave Clement and Alan Davies. And the list could go on.

Actually Bairstow also played football (with Bradford City) as well as first-class cricket, as did Stuart Leary, a 1950s and 1960s hero with Charlton Athletic and Kent CCC who threw himself off a cable car on Table Mountain in 1988.

If this grim casualty list of sportsmen from just two sports tells us anything (and it’s a partial list), then it’s likely that death at one’s own hand is not necessarily as uncommon as some might think – in any walk of life. And we just do not know, frankly, whether there is a statistically valid link between any sport and suicide, let alone why.

No major academic study had been done by 2011, although there is a dedicated Centre for Suicide Research at the University of Oxford.

Extensive studies there, for example, have found that the profession with the highest suicide rate in the UK is vets – who are four times as likely to kill themselves as the norm. And we know some contributory factors: stress from training onwards, long hours, high psychological demands, access to lethal drugs and knowledge how to administer them, a philosophical acceptance of euthanasia as a way to alleviate suffering, and exposure to suicides among colleagues that may result in “suicide contagion”.

The medical profession in general has a suicide rate at twice the norm for some similar reasons, while rates are also high among farmers for different and carefully identified reasons.

As for those who play games for a living? We can only guess. But we don’t know for certain that cricketers are any more likely to kill themselves than anyone else, let alone why.

My 2011 study attracted interest from various academics and five years later, in 2016, I was contacted by academics who had read the 2011 piece then conducted the first peer-reviewed academic study on the phenomenon of suicide among Test cricketers. They concluded cricket is ‘not to blame’ and there is no evidence of a higher incidence of such deaths among players than among the general population.

They wrote: “We began this study to determine if the idiosyncrasies of cricket were to blame for the high rate of suicide amongst male Test cricketers. That suicides occurred a median of 16 years after retirement suggests the importance of non-cricket-related factors.

“We conclude that ‘cricket is not to blame,’ given that the demographic, social and clinical characteristics of Test cricketers who committed suicide are similar to those in the general population.”

The study was led by Prof Ajit Shah of the University of Central Lancashire and involved psychiatrists Chanaka Wijeratne and Brian Draper of the School of Psychiatry at the University of New South Wales, Sydney. Their paper ‘Are elite cricketers more prone to suicide? A psychological autopsy study of Test cricketer suicides’ was published in the journal Australasian Psychiatry. An abstract of the paper is here.

It is important to note that it is specifically Test players who were considered. This gave the researchers a finite group of individuals to study from whom to draw conclusions, rather than a group much less easy to quantify effectively, such as “cricketers”.

The methodology of the study was similar to that used in psychological autopsy studies, covering demography and each player’s cricket career, post-cricket occupation, retirement issues, mental and physical health, substance use, details of the suicide, and life events in the year before suicide.

There have been few suicides of active players. Indeed the only cases of Test players below the age of 40 were Scotton (aged 37 in 1893), South Africa’s Vincent Tancred (who shot himself aged 28 in 1904) and Billy Zulch of South Africa, aged 38 when he died in 1924.

The paper said: “Most [victims] had been retired for over a decade and were middle-aged or older … The overall picture from the psychological autopsy was not particularly different from what could be expected in the general population of middle-aged and older male suicides.”

When pondering whether to write this particular piece, I looked at the coverage of Graham Thorpe’s untimely passing and noticed a) how sensitively it was covered - we are all so much more aware these days of myriad issues around mental health, and b) how several reports or features mentioned that cricketers are more likely to kill themselves.

That isn’t actually true.

Life can be a fragile experience for anyone.

As Peter Roebuck wrote when he penned the foreward for Frith’s first book in 1991: “Be gentle with yourselves, my friends, and do not expect more of life than it can give.”

Thank you for reading. This site is only sustainable via contributions for paying subscribers. If you’ve read this piece and taken anything from it, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.