"Ed Weston lived life a little differently from most of us, on a separate key and with the volume turned all the way up"

Once upon a time, for a few short years, six-day walking races were the biggest attractions in global sport. And at his peak, Ed Weston was the world's greatest walker

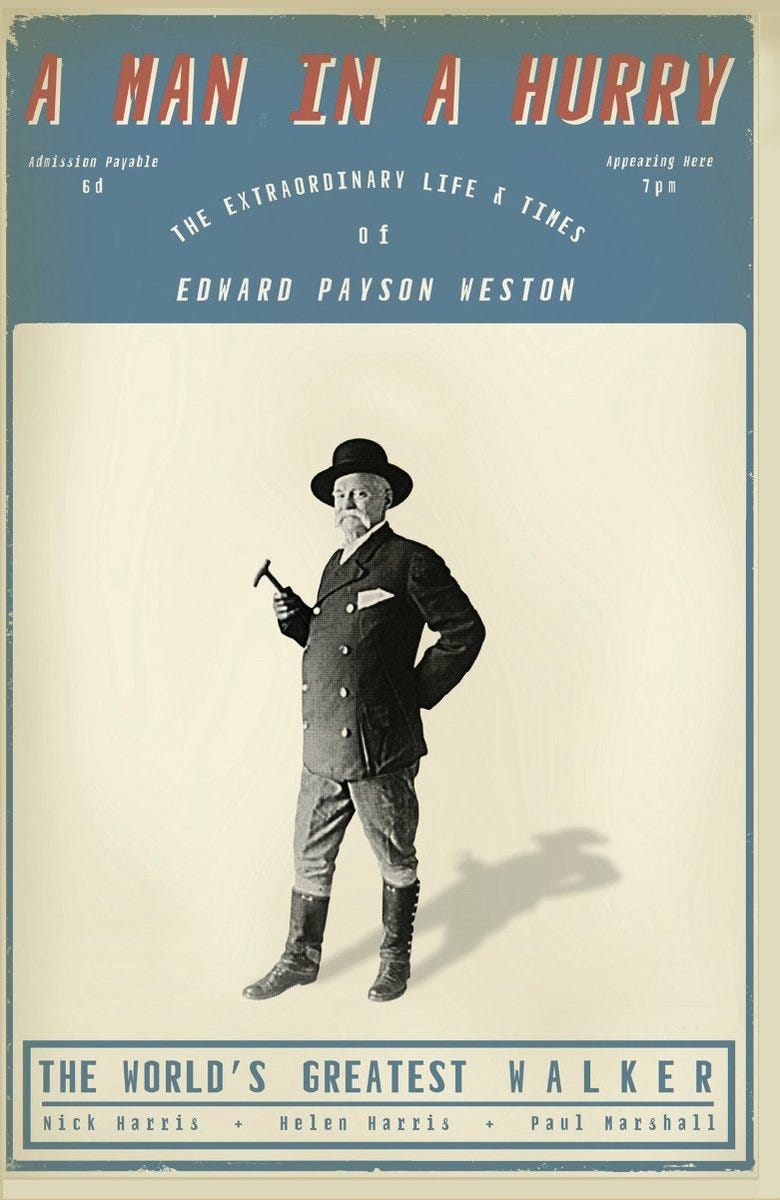

The best review I’ve ever had for a book I’ve written was in 2012, when Brian Phillips wrote a fabulously entertaining piece for Grantland about A Man In A Hurry, a biography of Edward Payson Weston, who was once among the most famous people in the English-speaking world.

You’ve almost certainly never heard of Weston. You’ve almost certainly never heard of the craze of professional pedestrianism, which peaked in the 1870s, when it was the best-attended “sport” in the world.

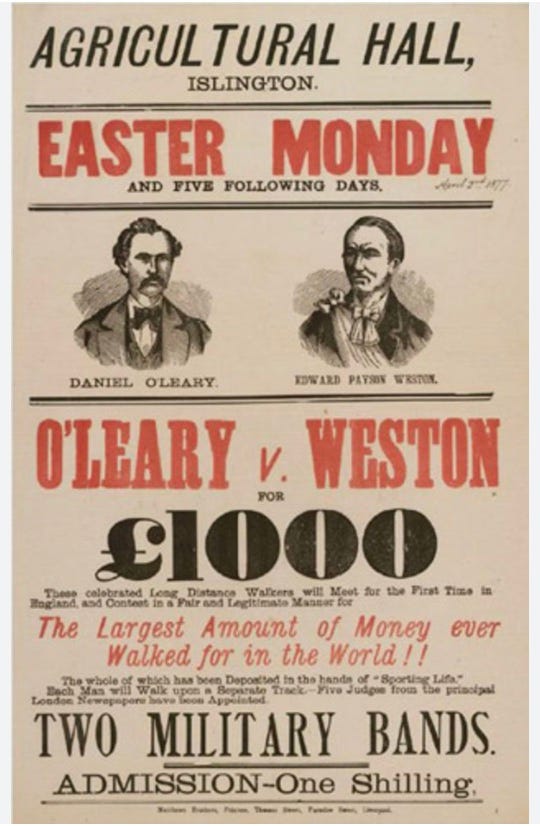

Crowds of tens of thousands would pack venues such as the Royal Agricultural Hall in London (now the Islington Business Design Centre) or Madison Square Garden, New York, to watch a group of men walk round and round a track, pretty much non-stop, 24 hours a day, for six days.

This was an era before codified professional sport existed. It was pre-football (soccer) and pre-baseball and pre-NFL by many decades and pre-basketball. It was absolutely bonkers: blokes (always men), walking perhaps 500 miles in six days around a track until some of them literally dropped, their feet a mess and their bodies drained.

Massive crowds paid good money to come and watch, for an hour or a day or the whole of an event, and to drink and smoke – and to gamble on the outcome. Money was a big ingredient in the phenomenon. Walkers raced for enormous cash prizes, and more money still was wagered on who won. More often than not, when it mattered, Ed Weston won.

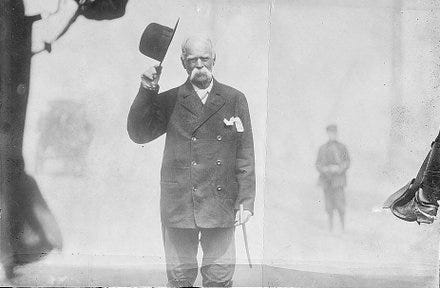

During his long, extraordinary and often controversial life, he worked in journalism and publishing and above all self-promotion, mainly through his walking, travelling widely across America and Great Britain. PT Barnum, the legendary circus promoter, was his contemporary and friend, as were other prominent showmen, musicians, writers, businessmen, royalty and prominent politicians.

I’d written a feature about the golden age of pedestrianism for The Independent in 2009, having read a 500,000-word quasi-academic book by on Weston by historian Paul Marshall. I felt Weston’s story was worth telling in a more accessible way.

I spent a long time researching his life and began a correspondence with a surviving descendant, Joyce Litz, who had a trove of family diaries and materials she shared that threw fresh light on his life - and lineage.

Not that it’s relevant to his athletic achievements but he was a direct descendant of one of the Pilgrim Fathers, and as such, part of the same vast family tree that links, among many others, Barack Obama and George W Bush. Ed Weston was (is) the seventh cousin, five times removed, of princes William and Harry.

He wouldn’t have known that when he was alive, of course, because he was born in 1839 and he died in 1929, and led an astonishing life that ran from the Gold Rush to the Jazz Age. He walked coast to coast in America in his 70s, twice, greeted by half a million people on the streets of New York at the end of one of those journeys. This is one crazy (true) story.

By 2010, with much of the research done and a book deal signed, I was head-hunted for a staff job as an investigative journalist at a national Sunday newspaper. I was already running Sporting Intelligence. Two full-time jobs were my limit. My wife Helen, a brilliant writer, had been struggling to get back into work after taking years off to raise our daughters, and had become fascinated with Weston after listening to me rambling on and on about him.

“I’ll finish the book,” she suggested one evening. Given that there were only a few chapters fully finished at that point, it wasn’t so much a case of “finishing” the book as writing it.

When it was published in 2012, it had some good reviews, including that amazingly entertaining piece by Brian Phillips (just read that and save yourself 12 quid), and we were hopeful that a Hollywood impresario would inevitably buy the movie rights.

Actually there were two expressions of interest about the movie rights but it it didn’t get optioned, and life went on, and we’d enjoyed doing it, and the girls had loved the trip to London in 2012 for the book launch. And that was that.

Twelve years after A Man In A Hurry was published in 2012, only as a hardback, it’s out again, as a paperback, from today. If you’re a paying subscriber to this site at the end of this month, you’ll automatically be entered into a draw to win one of five signed copies of the new edition.

There is a poignancy to this. Helen wrote about Weston and her investment in his story in 2012, the year of publication. She was later diagnosed with brain cancer in 2016, and died in 2020, something I’ve written about.

I was going to write a piece about Ed Weston to promote the release of the paperback. But Helen wrote her piece below in 2012, and I don’t think I can say any of this better. So, over to Helen.

By Helen Harris (from March 2012)

Ed Weston was an “endurance athlete” and a “sporting superstar” many decades before either of those phrases was coined.

If he’d been alive today, his athletic achievements would be covered in the sports pages of the broadsheets and his private life would be on the front pages of the tabloids.

Some of his many female admirers would, no doubt, have kissed and told. Possibly he wouldn’t have minded, although his wife might.

He wouldn’t have been too enamoured at being at the heart of a ‘coke scandal’. Actually he wasn’t thrilled when he was. The British Medical Journal broke that scoop. In 1876.

Over the past year, I have co-written Edward Payson Weston’s life story; it is the tale of an American athlete who, in the late 19th century, became one of the most famous people in the western world.

He thrilled and alarmed his compatriots. He spent years in Britain, and time in Paris.

I am no sports nut and before last year would barely have imagined reading a sports book let alone writing one, but Weston’s turned out to be an absorbing and compelling story which was, luckily for me, about a lot more than sport.

A Man in a Hurry tells the tale of how Weston, born in Providence, Rhode Island in 1839, took up a now largely forgotten sport, ‘pedestrianism’ and how by the 1870s he had turned it into an international craze.

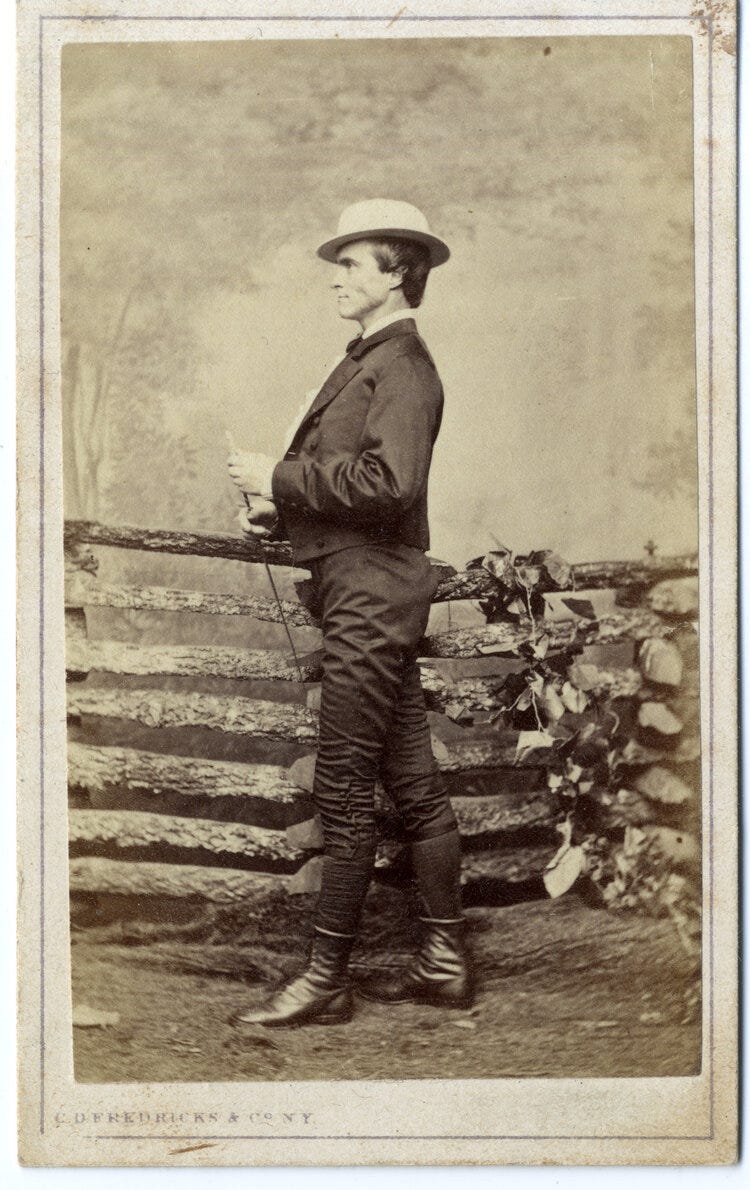

But it is also about an unlikely champion, a baby who seemed too tiny to live but grew into robust boyhood, only to became a frail, sickly teenager and then a man with a physique like a ‘potato stuck with two cocktail sticks’ who became a record-breaking endurance athlete by the force of his character.

Weston’s sport involved walking races or trials over long distances, indoors or on the road. One of his earliest world records saw him walk 100 miles in 24 hours; in the 1870s, pedestrians most frequently competed over six days, making distances of more than 500 miles.

Ed Weston was one of those people who lives life a little differently from most of us, on a separate key and with the volume turned all the way up.

He left home for the first time, aged 11, to tour the eastern States with a famous band of musicians. A few years later, he joined one of America’s biggest and best known circuses but was sacked, so he claimed, after being struck by lightning and feeling too ill to perform.

Still in his teens, he dabbled in publishing then went on to work as a journalist on James Gordon Bennet’s New York Tribune.

Weston was always bumping into the rich, the famous and the historic. During his career, he met four US presidents, knew PT Barnum and was a friend of New York newspaper legend Horace Greeley and of the English MP Sir John Astley.

It is typical of his story that his life in sport began with a bet on the outcome of the 1860 US presidential election, Abraham Lincoln versus Stephen A Douglas. Weston backed Douglas, lost the bet but found a calling. His forfeit was to walk from Boston to Washington in ten days to attend the new president’s inauguration. The 478-mile walk was his first pedestrian feat.

Then the Civil War put Weston’s career on hold for a few years later, but in 1867, with a 1,000-mile walk from Portland, Maine to Chicago, he became a household name, the talk of America. US newspapers covered every stage of a journey that was rattling with controversy.

There were rumours that Weston was in the pay of a corrupt New York politician, that he was going to throw the race and there were death threats against him. On the plus side, he was met by noisy crowds of fans, by brass bands and flags in every town and village he walked through.

And he was a great hit with the ladies: they blew him kisses and waved their handkerchieves, one even broke into his hotel room to catch a glimpse of the hero changing his clothes.

His sport had been slowly developing for more than 100 years before he came along – since English aristocrats had started betting on who had the fastest footman.

Then during the early 1800s numerous amateur pedestrians, walking alone, set records over 40 or 50 miles. But pedestrianism stayed on the margins of sport until, in the 1860s, Weston came along and within a decade turned walking into a hugely popular spectator

event.

What he brought to the party was his personality. He was a fantastic athlete, capable of walking 80 miles without stopping, but he was also a terrible show-off, given to singing and clowning around during races. He was at least two parts showman to one part athlete, a recipe that made walking races (essentially a man or men walking round and round a track, hour after hour) so dramatic and entertaining, not to mention controversial, that they began to draw audiences of up to 20,000 people a day.

Weston’s sporting career peaked when he was in his early 40s and walking in international contests, the so-called Astley Belt races, in London and New York. At the age of 47 he retired briefly but seemed unable to live a quiet life and, in fact, he kept on walking into his seventies.

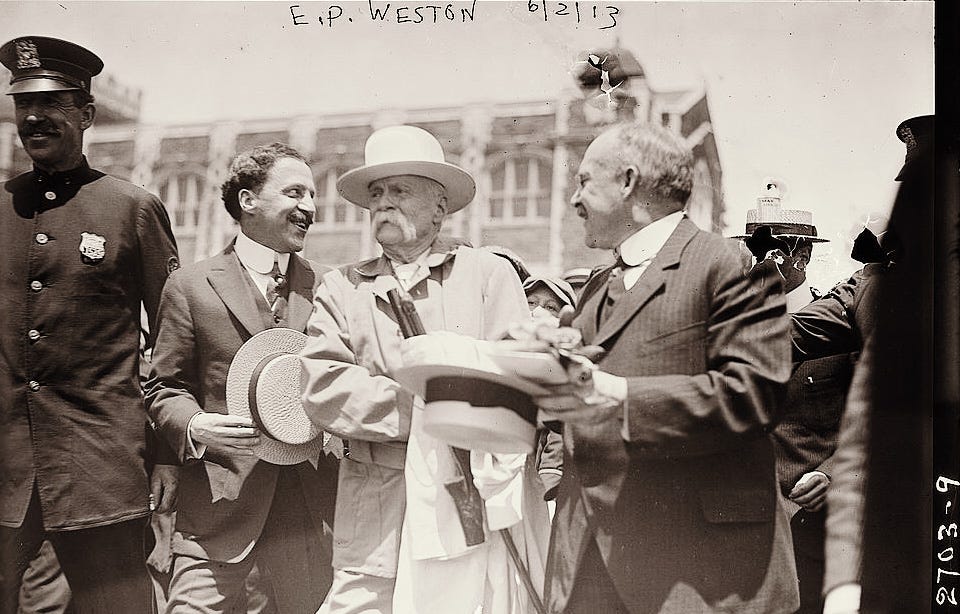

On his 70th birthday he set off to walk right across America, from New York to San Francisco. At the age of 72, he completed a second ocean-to-ocean hike, from Santa Monica to New York and was cheered into New York by a crowd of hundreds of thousands.

His personal life was colourful too. When his marriage broke up after 30 years, he set up home with a much younger woman who was referred to variously as his niece, secretary or adopted daughter. Annie O’Hagan stayed with him for the rest of his life, though they never married, and when Weston was in his eighties their unconventional living arrangements put his life in danger.

Thanks to Weston’s fame many details of his life were reported, often in gloriously fruity style, in contemporary newspapers, especially in the New York Times and in the Sporting Life. It was these details, the fascinating incidents of his life and times and the cast of quirky supporting actors that really drew me into Weston’s story.

One of these bit-parts belongs to Weston’s great rival, Daniel O’Leary, an Irish-born Chicagoan who had the gift of the gab, a fatal weakness for ale and a splendid, glossy head of hair.

The race events themselves were appealingly chaotic. Dogs and toddlers wondered onto the race track while the walkers pushed themselves to mad extremes in pursuit of victory. They staggered into exhaustion, retired for a swig of champagne or beef tea (according to taste) then tottered on for another few miles before finally collapsing.

During the longer races, competitors camped out in tents or huts inside the track and brought their families with them. During a six-day race at London’s Agricultural Hall in 1878, one walker, William ‘Corkey’ Gentleman, a poor East End cat-food salesman, had his wife Amelia installed in his tent throughout, keeping a pot-full of eel stew bubbling for him.

Weston died in 1929, just before the start of the Great Depression. He had been born 10 years before the Gold Rush, lived through the Civil War and the First World War, through the final stages of Washington’s conquest of the Indians and the wilderness and he saw the beginning of its accession to the status of a superpower.

By the time of Weston’s death, pedestrianism had gone, baseball, American football and soccer had taken over the audiences, and cars had taken the roads.

When Charles Dickens traveled to America for the first time in 1842, what he saw seemed to him as big and bright as a pantomime, so vivid it made him laugh out loud.

When I was researching A Man in a Hurry, everything I read about Weston, his life and time had that pantomime quality too, like our time but in technicolour, like going over the rainbow.

Hopefully, the book manages to capture some of that colour.

If you enjoyed this piece, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. There will continue to be regular free pieces for all readers, but from later this month I’ll be running a major, in-depth series each month on one particular subject - and these series, which will run across several days, will be exclusively for paid subscribers.

I’m currently working on a major project for later this month on football ticket prices, always a hot topic. In June the major series will revolve around Euro 24, including predicting the winner based on the insurable value of the players, while in July there will be a Wimbledon special, which will include a deep dive into a match-fixing doper in SW19. Don’t miss out - sign up now!