'Disappointed and depressed' - one woman's battle to clean up FIFA

A new book - extracted today - details a year in the life of Lise Klaveness, head of Norway's FA and a rare champion for change in the governing body

Attempting to reform global football, so long a bastion of male privilege, has defeated numerous campaigners down the years. The era of Sepp Blatter and the overwhelmingly corrupt ExCo that sent the 2018 World Cup to Russia and the 2022 event to Qatar was only swept away thanks to the work of the US Department of Justice.

Blatter was replaced by Gianni Infantino, who seems even more entrenched and all powerful than Blatter ever was, enjoying close relationships during his tenure with Vladimir Putin, the rulers of Qatar and most recently Mohammed bin Salman’s Saudi Arabia, which is pouring cash into FIFA and will host the 2034 World Cup after an opaque ‘bidding’ process.

Opportunities these days to hold FIFA to account or even to ask questions at press conferences are few and far between. ‘Why invite extra scrutiny?’ seems to be the approach.

Infantino continues with the strategy that first got him elected to FIFA’s top job in 2016: give more and more money to the voters who will keep him in place. It works.

For anyone attempting to make meaningful change to this swamp, it is close to impossible. That a young woman continues to try to do is more notable still. Which is just one among many reasons that Lise Klaveness is such an impressive figure.

The 42-year-old is a former footballer turned lawyer, was capped 73 times for Norway, and has been the president of the Norwegian Football Federation since March 2022. She was particularly outspoken in her calls for safer conditions and better pay for migrant workers in Qatar, and in her criticism of FIFA for sending the World Cup there in the first place, given Qatar’s anti-LGBT laws and oppression of women.

I spent some time with Klaveness at the recent Play The Game conference in Trondheim, where she gave an impassioned speech, which you can watch here, from 56min 30sec onwards.

There are so few women in leading roles across FIFA’s 211 footballing nations it is possible to name them all in a paragraph: the US Soccer Federation president Cindy Parlow Cone is in that group, as is the Canadian FA’s interim president Charmaine Crooks, the Belgium FA president Pascale Van Damme, the Turks and Caicos president Sonia Bien-Aime, the Belgium FA president Pascale Van Damme, the chairs of the Icelandic and English FAs (Vanda Sigurgeirsdóttir and Debbie Hewitt) and the CEOs of the FAs in Estonia (Anne Rei) and South Africa (Lydia Monyepao).

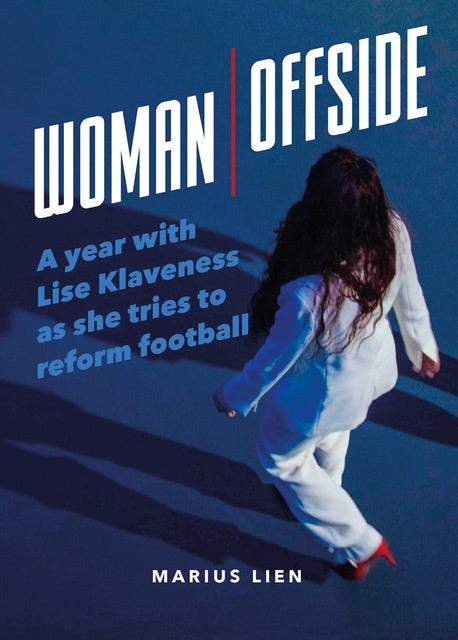

Today, March 8, which is International Women’s Day, a new book is published about a year in the life of Klaveness as she tried to make a difference in 2023 to the way football is governed. Sporting Intelligence carries extracts below of ‘Woman Offside: A year with Lise Klaveness’ by Marius Lien.

Lien is a Norwegian journalist known for his insightful reporting and investigative work. He has covered a wide range of topics, from politics and social issues to culture and the environment.

Extracts from ‘Woman Offside: A year with Lise Klaveness as she tried to reform football’, by Marius Lien.

Prologue

When Lise Klaveness entered Qatar’s capital Doha in March 2022, only two things were missing: the donkey and the palm leaves. The newly elected Norwegian football president was about to give a speech during the FIFA Congress — and the expectations were enormous. A messiah for a corrupt football world, on her way into Jerusalem! For many football lovers, Klaveness represented something pure and unadulterated, without really having done anything special for it. As expected, her speech caused a stir.

“Our members demand change; they question the ethics in sport and insist on transparency. They are getting organised to make their voices heard. We must listen! We cannot ignore this call for change (…) The migrant workers injured - or the families of those who died during the build-up to the World Cup - should be cared for. FIFA, all of us, must now take all necessary measures to really implement change.”

Immediately afterwards, the Honduran football president went to the podium, and stated that the congress was the wrong forum for that kind of talk.

The head of the Qatar World Cup was furious and criticised “Madame President” for not asking for a meeting in advance. FIFA president Gianni Infantino reacted with total silence. At least outwardly. However, back home in Norway, her speech was met with resounding applause. Klaveness received an honorary award from the free speech organisation Fritt Ord. The biggest newspaper, VG, which in the years before had given Qatar neither substantial criticism nor women’s football the support it merited, wrote in the opinions section, “Klaveness’ brave speech: Medicine in every word.”

“Extreme courage,” said culture minister Anette Trettebergstuen from the Worker’s Party, a party who hardly raised its voice during the huge debate over a boycott of the Qatar World Cup the previous year. Another big newspaper, Bergens Tidende, wrote, “Norway has become a country that finally dares to speak out properly.”

Suddenly we were a nation of proud FIFA critics. The speech was quoted in media around the world and received strong praise in parts of the football community, for example, in England and Germany.

Klaveness continued speaking out during the World Cup itself. After Infantino’s infamous “Today I feel Arab” speech - where he claimed that criticism of the Qatar World Cup was based on racism and colonial arrogance - she said that the FIFA president uses “the same rhetoric as dangerous and scary state leaders”, according to Norwegian channel TV 2.

Klaveness criticised Infantino for failing to meet with her since he is, after all, “everyone’s trustee”. She also actively looked for an opponent to Infantino during the next FIFA presidential election, but found none. Her year ended with a sprinkling of awards. Klaveness was, among a bunch of other things, chosen as Name of the Year in the newspaper VG and ‘Bergen Citizen of the Year’ in Bergensavisen—the newspaper from her hometown and Norway’s second largest city.

In Norway, and to a smaller degree internationally, this has created a view that Klaveness is a revolutionary who can fix everything that’s wrong with football. The belief is a bit like Argentina simply playing the ball to Lionel Messi and then sitting back, hoping that it will all work out. Argentina won the World Cup in Qatar using this method, but how much is really possible to accomplish in the football world as the president of the federation of Norway?

For many years, I’ve worked as a journalist in the Norwegian football magazine Josimar. We’ve covered all parts of the game, including a long list of articles and one entire issue dedicated to the Qatar World Cup. We’ve also looked extensively into the troublesome politics of world football, and the sport’s dubious connection to non-democratically elected state leaders.

For this book, I followed Klaveness for one calendar year (2023). At the start of the year, I asked what plans and ambitions she had for the next 12 months. I was by Klaveness’s side throughout 2023 to document how her work to change how the football world looks from the inside.

Lisbon, April 2023

Two days before the UEFA Congress, and one day before the awarding of the European Championship 2025 is to take place, the photographer and I meet Klaveness in a cafe outside the congress hotel in Lisbon. In advance, I’ve tried to find out what the other candidates stand for. Klaveness gives interviews everywhere: Forbes, Sky Sports, Reuters, Ekstra Bladet, and many more, including every major outlet in Norway. No one else does anything like it. In fact, none of them talk to the press at all.

Her own reflections are well received by the press, but behind the curtains at UEFA and FIFA, it is more up and down. We enter the UEFA hotel where Klaveness is doing a half-hour interview with the Dutch national broadcaster. When the microphones are switched off, the Dutch journalists talk about a point of view that is circulating — Lise appears too activist. Klaveness’s response: “Who says so? Who? WHO?”

But she doesn’t get an answer and has to move on to the next meeting. In two hours, the FIFA dinner begins, and in those hours five or six federations are on her meeting list, including the Balkans and the Baltics once again.

Other candidates work differently. Liechtenstein’s football president Hugo Quaderer, who is also up for election to the UEFA board, sits in the hotel bar. He is surrounded by seven or eight other men in suits. One of them is the Hungarian Sandor Csányi: banker, billionaire and vice-president of the UEFA board. The drinks are brought to the table non-stop; the glasses are emptied and the atmosphere is good.

At the other end of the bar sit former footballers Luis Figo and Robbie Keane, both caught up in the UEFA system for a long time. Csyáni stops by them, while Quaderer—who due to a “tight schedule” declines to give me an interview during the congress—smiles and toasts to the right and left.

The next day, UEFA’s committees have their meetings: the committee for gender and equality rights, the financial committee. Klaveness uses the morning to work her way down her own list. Will she reach her goal of speaking to all of UEFA’s 55 member states before the election?

The UEFA ExCo has a meeting from 1 p.m. The main purpose is to decide who gets the women’s European Championships in 2025. Sixteen of the board members are entitled to vote. For the first time, there are four applicants for the Euros: France, Switzerland, Poland and the Nordic countries. In the past, it was difficult even to find anyone who wanted to host the championship at all. As recently as 2020, there was only one applicant (England). At the meeting, the board members are given small catalogues that present the various bids. In addition, each applicant has five minutes to present their bid. Then the ExCo casts its secret votes.

Everything happens behind closed doors. There is no press conference afterwards for the board members to explain their decision.

UEFA’s original plan was to send out the result in a press release, but this was gradually upgraded to be a strictly guarded session with the press. Klaveness is present. Denmark’s president Jesper Møller finally ends up next to her—if he still hasn’t replied to her text messages, they can at least exchange a few words now. The other bidding federations are also there, as well as a couple of dozen journalists.

Then Alexandr Čeferin enters the stage. He says it was a close race. They needed three rounds of voting to get a winner. He opens the envelope ... and the winner is Switzerland. Jesper Møller resolutely gets up from his chair and disappears out of the room and further down the hall, without answering me or the others who call for him to give an interview. Lise Klaveness and Sweden’s new football president, Fredrik Reinfeldt, who is a former prime minister from the conservative party Moderaterna, take on the job of talking to the press about the defeat.

In the buzz, it comes out that Switzerland spent half of its five minutes on a rap song performed by a 17-year-old girl. The Nordic countries provided a PowerPoint presentation and a film. According to the grapevine, certain ExCo members almost proudly expressed that they had not bothered to read the various catalogues. Unlike before, Klaveness now expresses a certain exhaustion.

“I’m just disappointed, really depressed,” she says.

The 17-year-old rap artist was a perfect match for the men in ExCo. The Nordic PowerPoint presentation fell through.

Doha, November 2023

In November Klaveness travels to Doha, where she is following up on promises to monitor Qatar’s World Cup human rights legacy. Klaveness contacted a number of other federations in order to create a larger travelling party. The interest was lukewarm. FIFA’s working group on human rights prove uncontactable. In the end it is just her and two NFF colleagues.

On her final day meeting stakeholders in Qatar, she meets with two Gambian teenagers, Amadou and Bubacarr, who had travelled to Qatar to work as security guards, but had been left unpaid and stranded – a familiar fate for migrant labourers. They have taken their case to court, but come up against the absurdities of the Qatari judicial service again and again.

Amadou and Bubacarr are used to waiting. It’s almost a year since they had any work, and seven or eight months since they went to trial. They aren’t allowed to work; they largely spend their days staring at the ceiling. On weekends, they are forced to stay inside the state-run shelter all the time. On weekdays, they can be granted short trips out but only if they provide a very good reason and present it to “Madame”. That’s what they call the head of the shelter, Fatma Al Kuwari.

“But we must have a driver with us who looks after everything we do. Today we were lucky, the driver was going to accompany some female workers, domestic workers. They had to go somewhere, so we were allowed to go alone. We said we were going to meet a friend from The Gambia who was going back to our homeland,” says Amadou.

Finally, Klaveness and her advisor Magnus Borgen come out of the hotel, accompanied by Steinar Krogstad from the trade union. Klaveness is excited about the meeting she’s just had with the state secretary.

“She comes from the Supreme Committee [for Delivery & Legacy]. It turns out that many of the people who work there have been transferred to the Ministry of Labour. Obviously, she has her objectives. She wants to show that the changes they have talked about have actually happened. But she is informal, you can talk to her,” says Klaveness.

Then she approaches the boys who tell their story, right up to their trial.

“But I have just been in a meeting with a state secretary,” says Klaveness. “She told me about the new arrangements. They have made it possible for everyone to file their cases digitally. Have you done it? Did you file the case digitally?” Klaveness asks.

“No,” replies Amadou. “But we have been to court many times.”

At regular intervals, the boys are told to appear at a court office in central Doha. There they are asked to sign an Arabic document that they do not understand. Then they are told that their case is still in the system. They must go home and wait further.

“We’ve probably been there seven or eight times now,” says Amadou.

The conversation between Klaveness and the boys continues. She digs into the details and tries to figure out exactly what has happened. The boys are not allowed to work. They have no money and no personal documents. They are awaiting trial. They must stay indoors. They want to get paid the money they are owed. They cannot afford tickets home. And as long as their case is in the system, they’re not allowed to leave the country at all, even if Qatar paid for their tickets. And what about FIFA, who promised to help?

“We contacted them, and they said they would get back to us. Since then, we haven’t heard anything,” says Bubacarr.

After about half-an-hour’s friendly conversation, both parties must move on. Klaveness has her appointments, and we’re getting close to the time when the boys must return to Madame. The NFF president says that it is outside her mandate to pursue individual cases of World Cup workers. She nevertheless promises to proceed with Amadou and Bubacarr’s case, with help from Steinar Krogstad and the trade union network. The first step is to find out exactly where the case stands in the system. Now everyone must leave, and this is done with a kind of agreement to meet for a ‘kickabout’ in The Gambia sometime in the future. Klaveness says she is “pretty good”, the boys say they’re “not too bad either”, they were on the winning team in a workers’ tournament held during the World Cup. Klaveness then jokes that this little five-a-side kickabout in The Gambia might not be a good idea after all, and they say their goodbyes with smiles on their faces.

On the way back to the Industrial Area, we stop at what was once Stadium 974. The plans to send the entire stadium to Africa have been put on hold. Now there is talk of sending it to Uruguay instead for the big jubilee matches in 2030, when the 100th anniversary of the World Cup tournament will be celebrated. Amadou and Bubacarr walk towards the stadium which they helped build as construction workers and later helped protect as security guards. Now the arena is half dismantled. The lower rows of containers are still present, while the upper ones have been replaced by gaping holes. Maybe the containers are in Africa, maybe they are somewhere else. Then Bubacarr’s phone rings. It’s Madame, who says that there’s only an hour until their curfew starts. If they’re not on their way home already, they better get on the move now.

Oslo, December 2023

Let’s take a look at how 2023 has unfolded.

Lise Klaveness was not elected to the UEFA board. The Nordic countries did not get hosting rights for the European Championship in 2025. Even though Norway’s proposal in Kigali was accepted, FIFA will not provide any information about the sub-committee for human rights and the committee has apparently done nothing. Infantino may have broken the rules when he gave the 2034 World Cup to Saudi Arabia. The cooperation between the Nordic countries has not gone smoothly, and out on the pitch the year has been bleak. We will not make it to the men’s Euros, and the women’s World Cup was a failure. Nor did the women manage to qualify for the Olympics, and they might be relegated to the second division in the Nations League.

“How would you sum up the year, yourself?”

“Now, the year is not over. At times, I think the way you do: there’s been some tough fights,” she says in mid-November, referring to the points mentioned above.

“The next [few] days we are facing international matches which may not be important for qualification,” she says.

The men’s team face the Faroe Islands in a private match, and then Scotland in the final qualifying match. The women face Portugal and Austria in the Nations League.

“But we are football people. For us, it is important to get a good feeling in those matches. At the same time, it is also important to find out how we as a federation can show support to those who provide help for those who suffer in the Middle East, with small things and big things. But I understand your question. I am just as passionate about the match against the Faroe Islands as I am about a World Cup match. That’s how I was as a player, too. In the memories, a World Cup match is bigger, but the feeling around the game is the same. For the women, it has been tough for several years. Because the situation out there is escalating. Portugal is good, very good. They weren’t before. It has also been tough because of the situation with Hege,” she says.

She is referring to Hege Riise, the national team coach who had to leave after the Oceania World Cup.

“Nevertheless, this autumn we’ve played well until now, even though the results don’t reflect that. The development has been good, but if it doesn’t end up with good results, the girls will go to the Christmas break without having nailed the last few games.”

“What about football politics in 2023?”

“It’s been tough. We knew I wasn’t going to be elected, but we still wanted to follow the debate about women’s representation and break that barrier. We have done that. Many of us worked hard towards something that, seen from the outside, ended in nothing. But we’ve had conversations with 55 countries who thought it was strange that we did not simply run for the designated women’s place on the board. We have learned a lot, and perhaps we have given others some perspectives as well. We’ve suffered some losses, taken a few hits. It was a big disappointment that we didn’t get Euro 2025, as was the change of coach for the women’s team, and the men not qualifying for the Euros. These are big, heavy defeats. The economy too, everything becomes more expensive for the grassroots football. But that’s the kind of thing that makes us addicted too. Like a child, I’m looking forward to every football match, every club meeting or tournament. We have a core activity that is fun. This is important to remember.”

“Norway must find a position where we focus on our opportunities.

“We can’t do anything about the fact that we’re small, that it’s cold, that we don’t have the same money as Manchester City. But we have other strengths. Compared to others, we work closely together, we trust each other, we have gender equality and so on. We are a small fish in a big ocean. The question is: how are we going to swim?”

‘Woman Offside: A year with Lise Klaveness as she tried to reform football’, by Marius Lien, is published today Buy the book direct from Fair Play Publishing, £14. Also available via Amazon (£12.99 paperback and £6.99 Kindle) and all good book shops.